“To become a Keeper of the Light House on Bald Head”

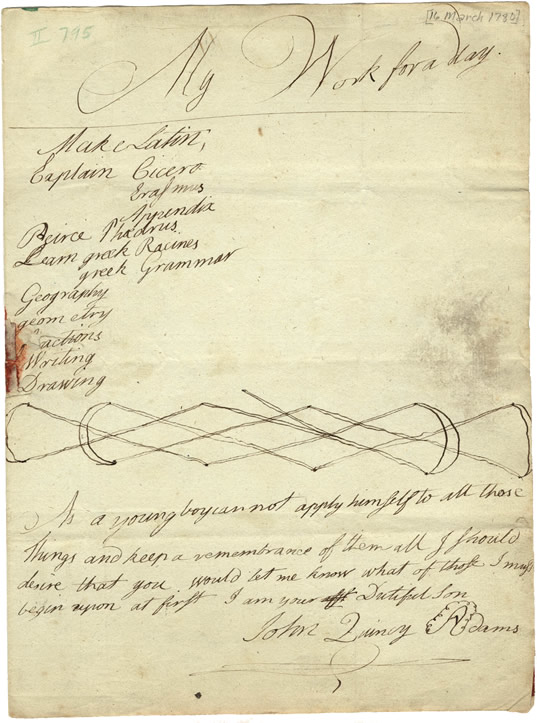

It begins:

Historians have long wondered what prompted President Thomas Jefferson’s cryptic sentence in a note dated January 13, 1807, to Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin: “The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I.”As Paterson says, Gallatin’s letter to the President and other pertinent documents don’t survive, so he had to work with other sources. One key bit of news:

Given Jefferson’s opinion explicitly expressed elsewhere that women were best suited to domestic roles, not to boisterous public political forums, and not as actors in the halls and offices of government, scholars of the early republic and popular authors alike, since at least 1920, have tried to reconstruct the specific context in which the president made this comment. For the last twenty years, the consensus explanation has been that Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, unable to find enough qualified men to fill federal government jobs, proposed hiring women for those positions.

However, while Jefferson’s statement may reflect his thoughts on women as office holders in general, my recent research in federal records proves that Jefferson wrote the sentence in reaction to Gallatin’s proposal to appoint a specific woman to a specific job.

The Wilmington (N.C.) Gazette of October 21, 1806, reported that five days earlier, a man named Joseph Swain, hunting deer and wild hogs on Bald Head Island, fired at a noise he heard in the bushes—only to find that he had killed his father-in-law, light-keeper Henry Long.Paterson’s research also indicates that Gallatin; Timothy Bloodworth, the federal Customs Collector at Wilmington; and twelve local men were all willing to see a woman appointed to the office in question. Only President Jefferson deemed that “the public” wasn’t prepared for that.

Nineteen years later, President John Quincy Adams made the opposite call in regard to the same type of federal office.

For additional reading, here’s Kevin Duffus’s article for Coastal Review on the slain lighthouse keeper, Henry Long. It turns out he was born in the Palatinate in 1743. At the age of ten his family emigrated to Maine, the same region where Christopher Seider’s family first settled. His father, a schoolteacher also named Heinrich Lange, was still there in 1767, according to Jasper Jacob Stahl’s History of Old Broad Bay and Waldoboro.

As a young man, Henry Long moved to North Carolina, which had German-speaking Moravian communities. He became a river pilot, married, and had children. Entering his fifties, Long seems to have wanted a more stable job. In 1794 the Hooper family—who also had roots in the Massachusetts colony—recommended him to the federal government to tend the lighthouse off Cape Fear. And that went well for twelve years.