from Henry Wiencek to Richard Potter

Common-place offers a terrific interview with Henry Wiencek, author of The Hairstons and An Imperfect God, about his research on how George Washington managed and lived with his slaves. Wiencek also talks about an intersection that can be equally awkward: between genealogy and history.

Common-place offers a terrific interview with Henry Wiencek, author of The Hairstons and An Imperfect God, about his research on how George Washington managed and lived with his slaves. Wiencek also talks about an intersection that can be equally awkward: between genealogy and history.

I think the topic of Washington as a slaveholder is fascinating because of how the first President struggled with the issue all his later life (and even, in a way, beyond). Washington always wanted to do the right thing by his society's standards. But on this question what was the right thing? The way he and his relatives and his peers in Virginia all lived, or what his principles told him to try? Occasionally I help perform a presentation on Washington and slavery assembled by ranger Paul Blandford at Longfellow House that looks at Washington's words and deeds on slavery.

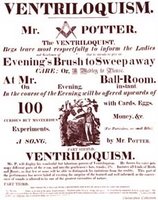

The New England population contained fewer slaves than the colonies to the south, and the plantation system didn't dominate society here. As a result, there were fewer enslaved children identified as the children of their white masters, the topic Wiencek explores in his books. One notable New England said to have that background was Richard Potter, often called the first American magician. At least, he was the first American to make a good living performing ventriloquism and conjuring on the stage.

Potter was born in Hopkinton, Massachusetts. Traditions in the magic community, exemplified in articles here and there and in this book reviewed on the Magic Cheese blog, say that Potter was the son of an enslaved servant named Dinah and Sir Charles Henry (Harry) Frankland, a British Customs official who had a country home in that town. For all sorts of reasons people might want to believe a prominent man of color was descended from a British baronet: the appeal of celebrity and transgressive gossip, racism (crediting Potter's success to noble European blood), a simple answer to who in Hopkinton had the power to impregnate an enslaved woman.

The only problem is that Potter, according to his gravestone, died in 1835 at age 52, meaning he was born in 1783. Sir Harry Frankland died in 1768.