The Resignation of Samuel Locke

I wrote about how the college had come to choose Locke back in 2020, on the sestercentennial of his installment.

Locke had been a star student at the college, where John Adams considered him the second-best classical scholar. He then had a quiet career as a minister in Sherborn, where he married a daughter of his predecessor (whose dowry included some good farmland) and started a family.

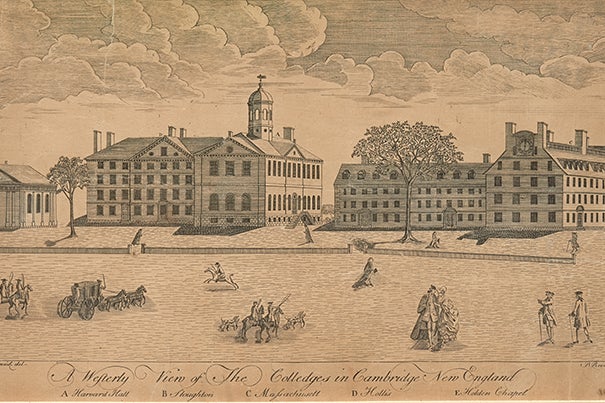

Locke wasn’t the Harvard corporation’s first choice to be president in 1770, and he took a long time to accept the job. It looks like the governing board wanted someone clearly different from the Rev. Dr. Edward Holyoke, who had served more than thirty years as president before dying at age seventy-nine. Locke would be the youngest Harvard president ever, and the board hoped he would modernize the teaching and scholarship.

Things appeared to have started off well. In 1772 the college gave Locke an honorary doctorate in sacred theology. The following June, the Rev. Ezra Stiles wrote good things about him, while wishing he would be more supportive of local resistance to the Crown.

And then suddenly Locke was gone. The official college records about his departure come from the minutes of a corporation meeting on 7 December:

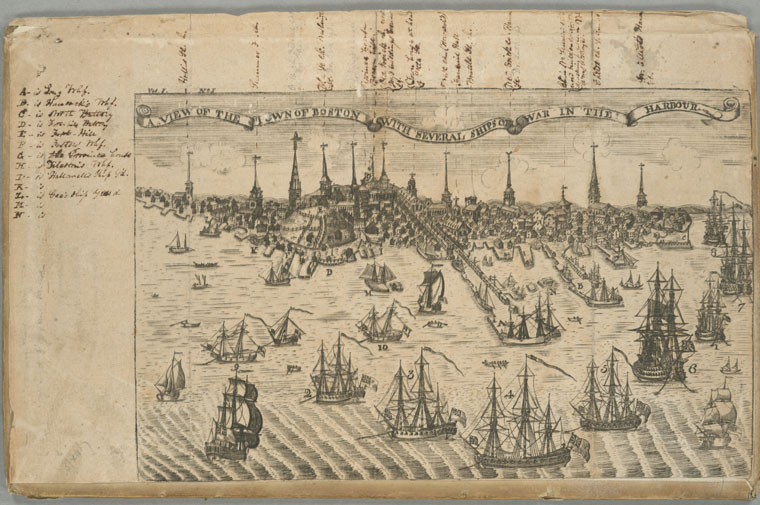

Dr. [Nathaniel] Appleton communicated a Letter from President Locke dated Dec. 1st 1773, signifying his resignation of the Office of President of this College. Voted. that the Revd Dr. Appleton, Professor [John] Winthrop and Mr. [Andrew] Eliot be a Committee to receive and take into their Care the Books Papers and other Things in the President’s house, that belong to the College and to receive the Keys as soon as the late President has removed his Family & Effects.Appleton was the Congregationalist minister in Cambridge, his meetinghouse right next to the college campus. Prof. Winthrop lived nearby. Eliot was a minister in Boston, someone who had turned down the office of president back during the last search. Now they had the task of tidying up after President Locke.

TOMORROW: “The unhappy affair.”