In Parliament, 250 years ago this season, there was a big step forward in

press freedom to report about how English-speaking governments worked.

Back in 1731,

Edward Cave launched the

Gentleman’s Magazine, which among its features included detailed reporting on the debates in

Parliament, going beyond the official

House Journals record of motions and whether or not they were adopted. Cave had actually been jailed a few years earlier for publishing such reports. This time he issued his proceedings only during parliamentary recesses, which provided legal cover.

According to

James Boswell, Cave passed “scanty notes” on the debates to a young writer named

Samuel Johnson to turn into oratorical arguments. It’s not that surprising, therefore, that these reports were often distorted—or so the prime minister, Sir

Robert Walpole, complained.

In 1738, the House of Commons resolved:

That it is a high indignity to, and a notorious breach of the privilege of, this House for any news-writer in letters or other papers…to give therein any account of the doings or other proceedings of this House, or any Committee thereof, as well

during the recess as the sitting of Parliament, and this House will proceed with the utmost severity against such offenders.

The

London Magazine and

Gentleman’s Magazine then started to report on the debates as if they had taken place in ancient Rome, Lilliput, or the Robin Hood Society, thinly disguising legislators’ names. Another trick was to replace some letters of the Members’ names with asterisks or dashes. Because of the magazines’ slow publishing schedule and upper-class audience, it appears, the government didn’t press its objections.

In the 1760s, however,

John Wilkes brought more populist politics to London, with the business community and big crowds behind him. The capital’s newspapers increased their coverage of Parliament’s debates. That meant quicker reporting to a larger and closer readership.

The Houses responded by clearing all spectators out during debates, sometimes by force. At the end of 1770 the Whig M.P.

Isaac Barré complained about how he’d been pushed out of the House of Lords as if by “a very extraordinary mob” headed by two earls.

On 5 Feb 1771, a Member named

George Onslow asked for Parliament’s old rule against printing the proceedings to be read again. Onslow had started in Parliament as a

Rockingham Whig, opposing the prosecution of Wilkes and the

Stamp Act, but he’d become a strong supporter of

Lord North’s government, and he didn’t like how printers were representing it.

Opposition members of the House disagreed with Onslow’s proposal.

Charles Turner argued that “not only the debates ought to be printed, but a list of the divisions [i.e., votes] likewise.”

Edmund Burke said he wished all debates were fully recorded in the

House Journals.

Naturally, the press reported on that debate.

John Horne, a radical clergyman, prefaced the coverage in the

Middlesex Journal for 7 February with this line:

It was reported, that a scheme was at last hit upon by the ministry to prevent the public from being informed of their iniquity; accordingly, on Tuesday last, little cocking George Onslow made a motion, that an order against printing debates should be read.

Onslow took the bait on 8 February, rising solemnly to complain that the

Middlesex Journal and another paper, the

London Gazetteer, had misrepresented Parliament and brought it into poor repute. He demanded that the printers Roger Thompson and John Wheble be summoned to explain themselves. By a vote of 90 to 50, the House adopted Onslow’s resolution.

But those printers didn’t show up. They didn’t come to their front doors to accept warrants. On 8 March the Crown issued a proclamation offering £50 for apprehending the two men. Meanwhile, newspapers heaped more criticism on Onslow: “That little insignificant insect, George Onslow, was the first mover of all this mighty disturbance.”

On 12 March, Onslow demanded to hear from six more publishers who continued to run parliamentary reports. On the first vote the House supported him, 140 to 43. Another member suggested summoning not only the proprietor of each newspaper but “all his compositors, pressmen, correctors, blackers and devils,” which produced more argument over both legalities and language. The Whigs kept moving to cancel the discussion and adjourn; the majority kept voting to proceed.

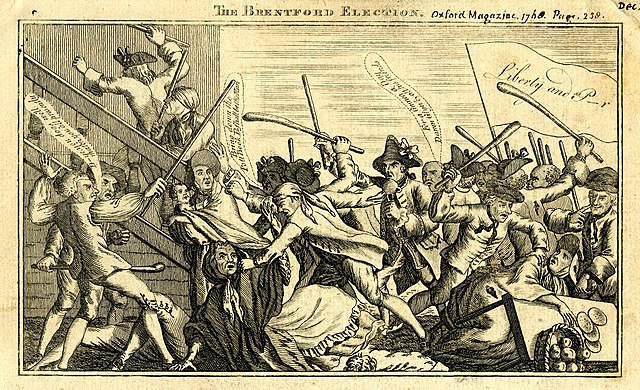

One account said, “There were so many divisions, and such strong and personally offensive expressions used during the course of this debate, that the Speaker [

Fletcher Norton, shown above] said, ‘This motion will go into the Journals—what will posterity say?’” After more votes Norton declared, “I am heartily tired of this business.” Barré spoke up: “I will have compassion on you, sir; I will move the adjournment of the House.” That motion produced another round of debate.

Of all the printers Onslow had named, two appeared in the House, ritually knelt in penance, and paid fines. The rest made excuses to stay away or just lay low. Some replied that they would come when the legal situation was resolved.

Wilkes orchestrated the next move. Wheble and Thompson let themselves be apprehended by fellow printers and brought before the aldermen of London—namely Wilkes and his political allies. Those officials demanded to know under what authority the printers had been seized. When the captors pointed to the proclamation, Wilkes declared such an order “contrary to the chartered rights of this city, and of Englishmen.”

The conflict between levels of government grew. The Crown arrested Alderman

Richard Oliver and the Lord Mayor,

Brass Crosby, for defying parliamentary authority. They remained in the Tower of London until the end of the legislative session, then came out to a twenty-one gun salute and a parade of carriages. Crowds hanged Onslow and Norton in effigy on Tower Hill.

Legally the “printers’ case” of 1771, as it was called, ended in a victory for the House of Commons. Courts upheld its authority to determine how its proceedings would be published. But politically everyone realized that the press and society were operating under new rules. British citizens now expected to read full reports of what their legislators were saying. Parliament never tried to exercise its authority so strictly again.

The only way legislative houses could regain control of the reporting process was to issue their own official or semi-official transcriptions of debates.

John Almon and

John Debrett launched the

Parliamentary Register in 1775.

William Cobbett began publishing more detailed

Parliamentary Debates in 1802, and that became the modern standard

Hansard Debates. That tradition transferred over to the U.S. of A., with the

Congressional Record, the Capitol press galleries, and C-SPAN as the offshoots.

_-_BHC2808_-_Royal_Museums_Greenwich.jpg/220px-British_School_-_Captain_George_Johnstone_(1730%E2%80%931787)_-_BHC2808_-_Royal_Museums_Greenwich.jpg)