“Not the only Instances of the unexampled Goodness”

As I quoted yesterday, on 24 May 1773 the Boston Gazette ran a delightfully bitter attack on Commissioner Charles Paxton for finding a job for Ebenezer Richardson in the Philadelphia Customs office.

A couple of paragraphs below that invective, Edes and Gill printed:

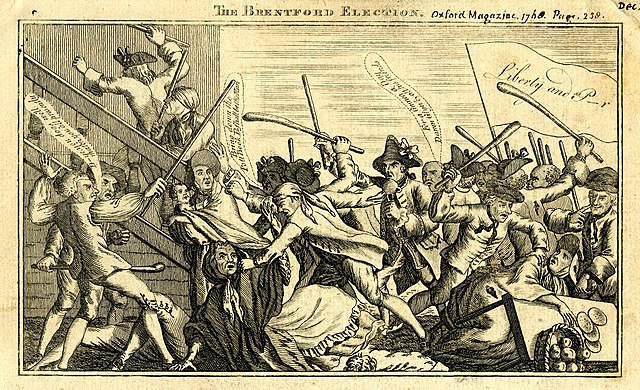

Laurence Balfe and Edward McQuirk (or Quirk or Kirk) were accused of hitting George Clarke on the head during a riot sparked by a by-election at Brentford in West London on 8 Dec 1768, as shown above.

The rival candidates in that election were Sir William Beauchamp-Proctor, a Rockingham Whig, and John Glynn, lawyer for the radical John Wilkes. (Glynn won and served in Parliament till his death in 1779.)

A “gentleman of very considerable fortune” testified that he had seen McQuirk and Balfe among Proctor’s supporters on the first day of voting. The two men were carrying clubs, and McQuirk was “very active in the fray.”

That night, the wealthy gentleman spoke to McQuirk and Balfe, letting them believe he was on their side. McQuirk admitted to having been in the brawl and hinted he might have to flee the country. Balfe said he’d been paid “a guinea for going down to Brentford.”

The gentleman took his information to a “parson Horne,” no doubt the political radical John Horne, then still a Wilkes ally. That man arranged for McQuirk and Balfe to be arrested by Sir John Fielding, the London magistrate. Clarke died on 14 December, elevating the charge to murder.

In January 1769 McQuirk and Balfe were convicted of murder at the Old Bailey, with the jury deliberating only twenty minutes. Proctor immediately launched a public campaign for royal clemency, calling this verdict unjust.

Advocates for mercy pointed out that the prosecutors never accused either defendant of hitting Clarke. Indeed, there was no evidence Balfe hit anyone, just that he was in the crowd. The Earl of Rochford also reported there was “some doubt whether Clarke’s death happened in consequence of the blow he received.”

On 10 March, the Crown pardoned McQuirk and Balfe.

Proctor was a supporter of the Marquess of Rockingham, and Rockingham had been mostly supportive of America during this first term as prime minister in 1765–1766. Furthermore, the case against McQuirk and Balfe really was flimsy, and they were obviously pawns in a much bigger game. We might therefore expect colonials to support clemency for them.

However, American Whigs were enamored of John Wilkes. They suspected any attack on his party as oppression by the establishment. Thus, Edes and Gill could present “Balf [and] McQuirk” as an example of George III or the ministers around him abusing the royal pardon power to benefit political supporters, just like Ebenezer Richardson.

TOMORROW: The case of the Kennedys.

A couple of paragraphs below that invective, Edes and Gill printed:

Some Time last Week Ebenezer Richardson, Esq; who lately had such a fortunate and surprizing Escape from the Gallows for the Murder of young SEIDER; through the extraordinary Clemency of our pious and gracious Monarch, set out for the City of Philadelphia, being appointed an Officer in the Customs, for this notable Exertions in Behalf of Government———This writer obviously expected readers to recognize those names, but I didn’t.

Balf, McQuirk & Kennedys are not the only Instances of the unexampled Goodness of George the Third.

Laurence Balfe and Edward McQuirk (or Quirk or Kirk) were accused of hitting George Clarke on the head during a riot sparked by a by-election at Brentford in West London on 8 Dec 1768, as shown above.

The rival candidates in that election were Sir William Beauchamp-Proctor, a Rockingham Whig, and John Glynn, lawyer for the radical John Wilkes. (Glynn won and served in Parliament till his death in 1779.)

A “gentleman of very considerable fortune” testified that he had seen McQuirk and Balfe among Proctor’s supporters on the first day of voting. The two men were carrying clubs, and McQuirk was “very active in the fray.”

That night, the wealthy gentleman spoke to McQuirk and Balfe, letting them believe he was on their side. McQuirk admitted to having been in the brawl and hinted he might have to flee the country. Balfe said he’d been paid “a guinea for going down to Brentford.”

The gentleman took his information to a “parson Horne,” no doubt the political radical John Horne, then still a Wilkes ally. That man arranged for McQuirk and Balfe to be arrested by Sir John Fielding, the London magistrate. Clarke died on 14 December, elevating the charge to murder.

In January 1769 McQuirk and Balfe were convicted of murder at the Old Bailey, with the jury deliberating only twenty minutes. Proctor immediately launched a public campaign for royal clemency, calling this verdict unjust.

Advocates for mercy pointed out that the prosecutors never accused either defendant of hitting Clarke. Indeed, there was no evidence Balfe hit anyone, just that he was in the crowd. The Earl of Rochford also reported there was “some doubt whether Clarke’s death happened in consequence of the blow he received.”

On 10 March, the Crown pardoned McQuirk and Balfe.

Proctor was a supporter of the Marquess of Rockingham, and Rockingham had been mostly supportive of America during this first term as prime minister in 1765–1766. Furthermore, the case against McQuirk and Balfe really was flimsy, and they were obviously pawns in a much bigger game. We might therefore expect colonials to support clemency for them.

However, American Whigs were enamored of John Wilkes. They suspected any attack on his party as oppression by the establishment. Thus, Edes and Gill could present “Balf [and] McQuirk” as an example of George III or the ministers around him abusing the royal pardon power to benefit political supporters, just like Ebenezer Richardson.

TOMORROW: The case of the Kennedys.

No comments:

Post a Comment