“The price of her husband’s blood”

This time the prosecutor wasn’t the Crown. Rather, as stated yesterday, Bigby’s widow Ann was suing them under an old and little-used English law that allowed murder victims’ families that privilege.

The Kennedy brothers had already been tried, convicted, and sentenced to hang in criminal court, but then reprieved by the Crown. They were about to be transported to America.

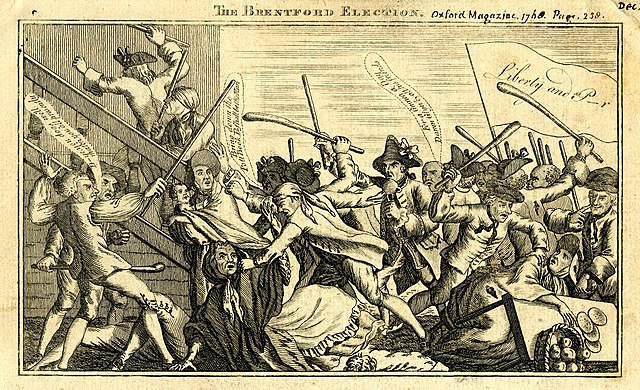

Activists opposed to British government corruption seized on this murder case because rich friends of the Kennedys’ sister Kitty, a popular courtesan, had obviously intervened on her brothers’ behalf.

In a public letter dated 28 May, the political writer Junius complained about “the mercy of a chaste and pious Prince extended chearfully to a wilful murderer because that murderer is the brother of a common prostitute.”

The Rev. John Horne and others in the Society of Gentlemen Supporters of the Bill of Rights encouraged Ann Bigby to sue. And if she won, the death penalty was back on.

So in May the Kennedy brothers were once again in a courtroom. Most of that first proceeding was filled with legalistic arguments of whether the procedure was even valid. The brothers were sent back to jail to await the next hearing. Their supporters complained that, too, was unjust (though other people were in the same jails for far less).

In August 1770, the American press started to run stories about the Kennedy brothers, catching their readers up with articles from London newspapers in March and May. Richard Draper devoted almost the entire fourth page of the 9 August Boston News-Letter to the case.

At the next court session in November, Ann Bigby “allowed herself to be non-suited.” Accounts offer different details, but they all agree that Kitty Kennedy’s friends paid off the widow.

One London publication said:

When she went to receive the money (£350) she wept bitterly, and at first refused to touch the money that was to be the price of her husband’s blood; but, being told that nobody else could receive it for her, she held up her apron, and bid the attorney, who was to pay it, sweep it into her lap.Decades later, John A. Graham wrote in his Memoirs of John Horne Tooke:

this gentleman [attorney Arthur Murphy, shown above] stepped in between them [the Kennedys] and the laws. The widow Bigby, the nominal prosecutor, was tempted by him, with a sum of money, to desist; and, after some hesitation between duty and avarice, actually accepted of three hundred pounds, which had been offered her in paper, on condition, that, to prevent the risk of forgery, the bank notes were converted into gold!Still, it took until the spring of 1771 for the murder case to be formally resolved. Then the criminal sentence and the commutation were both confirmed. As the 10 June Pennsylvania Chronicle told American readers, Matthew would be coming to America for life, Patrick for at least fourteen years—“which they accepted of.”

Drew D. Gray’s Prosecuting Homicide in Eighteenth-Century Law and Practice states that the Kennedy brothers arrived in Virginia before the end of the year. Like Elizabeth Canning, they seem to have shed their British notoriety and disappeared into colonial society—helped by having fairly common names.

(Or did they? In 1909 Horace Bleackley wrote in Ladies Fair and Frail that Matthew Kennedy was “seen in gaol at Calais, a prisoner for debt,” in 1775—but he offered no source for that statement.)

As for Kitty Kennedy, in August 1773 she married Robert Stratford Byron or Byram and retired from celebrity life. However, a few years later, she was back with the Hon. John St. John, one of her main lovers and helpers during her brothers’ court case. She died in late 1781 of consumption.

TOMORROW: This is supposed to be a story about Ebenezer Richardson.

.jpg)

Who was the source of those hints? I think the search has to start with the question of who in America would benefit from people believing that Gates wasn’t simply an ambitious child of hard-working servants who convinced their employer to help him become a British army officer. Who in American would like people to think that the retired general, remarried to a wealthy British heiress, was actually the son of a British lord? I can’t help but think that that list starts with Gen. and Mrs. Gates themselves.

Who was the source of those hints? I think the search has to start with the question of who in America would benefit from people believing that Gates wasn’t simply an ambitious child of hard-working servants who convinced their employer to help him become a British army officer. Who in American would like people to think that the retired general, remarried to a wealthy British heiress, was actually the son of a British lord? I can’t help but think that that list starts with Gen. and Mrs. Gates themselves.