Settling James Jackson’s Estate

James left no will, so on 25 September a probate judge appointed three people to administer the estate: William Speakman, baker; John Deacon, blacksmith; and Mary Jackson, widow. Speakman and Deacon’s names don’t appear in the probate file again.

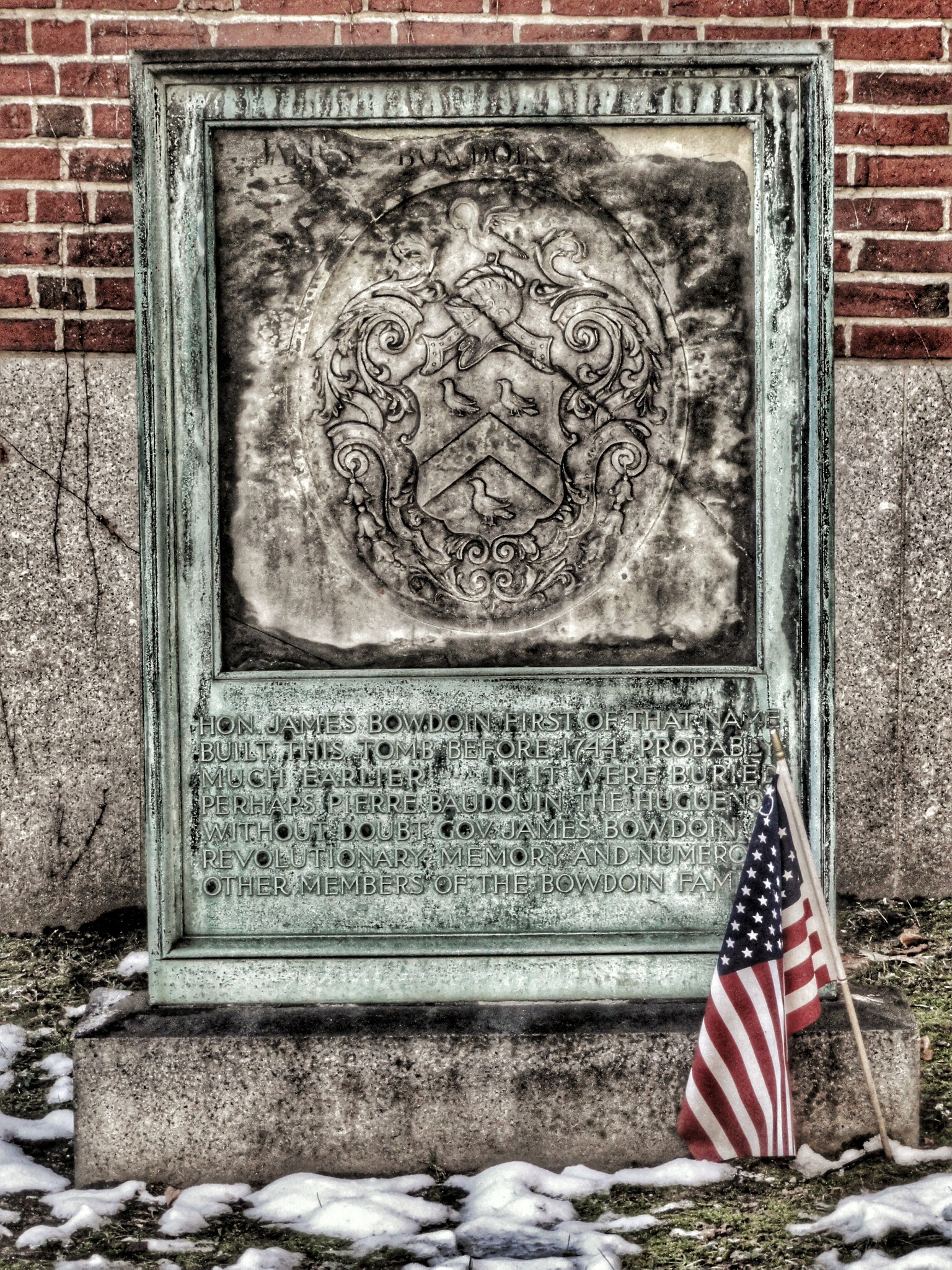

Mary Jackson in turn appears to have hired Leonard Jarvis, whose gravestone at Copp’s Hill illustrates this posting, to inventory the estate and settle some debts.

In January 1736, Jackson submitted a six-page inventory of her husband’s property. He owned no real estate. The hardware in the store started with “36 Pair of Large Brass Candlesticks” and totaled £1,469.11.8, plus about £100 of founder’s tools and raw metals. The household goods included a mahogany card table, an “old fashioned” looking glass, and 39 pieces of pewter tableware. All told, Jackson valued her late husband’s property at a little over £1,700.

That wasn’t the end of the probate process by a long shot, however.

In August 1737 the probate judge questioned five men about the Jackson estate, asking if they knew of any property not included in the inventory. From three of those men came news of:

- “old Iron & old brass carried into the Cellar to the value of one hundred weight”

- “some brass Patterns which were never shown to the Apprizers by William Who is run away”

- “old Cocks that came to be mended & a pair of old Hinges”

In November 1737 the court summoned Richard Fry, then back in Boston and feuding with Samuel Waldo. Fry owed money to the Jackson estate, with the security being a parcel of paper—“but it being So Bad that its for ye most part unvendible.” For papermaking fans, this parcel consisted of reams of “Large bag paper,” “Small Capp,” “Best Sorted Whited Brown,” “Whited Brown,” and a “Bundle.” Mary Jackson had sold most of the bag paper and best whited brown. The probate court empowered a committee to examine and value the rest.

The court had already commissioned those same men to sort out the debit side of the estate. On 24 July 1738, the Boston Gazette ran this notice:

The Commissioners to Examine the Creditors Claims to the Estate of Mr. James Jackson, late of Boston Founder, deceased, will meet once a Month at the usual time and place for Four Months longer, to Receive said Claims, of which the Creditors are to take notice.The commissioners filed their report in October 1738. They found that the James Jackson estate owed eighty-four creditors a total of £2,696.5.10. The biggest creditor, with over £1,650 due, was the wealthy merchant Charles Apthorp. The second largest, owed only £228, was James Bowdoin.

In yet another document for the probate court, Mary Jackson reported the total amount due to her husband as £1,787.6.9, and that she had collected £221 and a penny since his death. In that filing Jackson also included a list of expenses since her husband’s death, including payments to the commissioners and others who helped settle the estate, wages for a nurse, “weeds” for mourning, and necessary household expenses. That was enough for the judge to declare the estate settled in 1739.

Mary Jackson’s expense list reveals some details of her husband’s brazier business. She paid rent to William Dummer for the shop, separate from other rent, probably for where the family lived. She reported “the Expence of maintaining 7 persons during the Shops being shut up wch. was 4 Weeks.” I’m guessing those seven people included the five men interrogated about things removed from Jackson’s estate, plus the elusive William.

The four weeks’ closure sheds new light on this advertisement that had appeared in the Boston Gazette on 27 Oct 1735:

MARY JACKSON, the Widow of the late James Jackson Founder, at the Brazen Head in Cornhill Boston, sells all sorts of Founders Ware, and all sorts of bright Braziers Ware, and likewise Casteth all sorts of Mill Brasses.Having kept the Sign of the Brazen Head closed for a month, all the while paying the skilled staff to stay on, Mary Jackson had opened for business again.

TOMORROW: Mary Jackson, businesswoman.