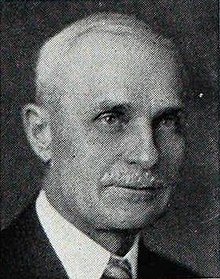

The

older boy wounded by

Ebenezer Richardson’s shot on 22 Feb 1770 was nineteen-year-old

Samuel Gore.

He appears here in his early-1750s portrait by

John Singleton Copley, a detail from a

painting now at

Winterthur. Of course, this when Sammy was still a toddler and Copley was still developing his technique.

In contrast to

Christopher Seider, a

servant born to poor German immigrant parents, Sammy Gore came from an old New England Puritan family that was rising swiftly in society. The portrait of the kids was one sign of that social ambition, even if the young artist might have done it for practice or in barter for paints.

Sammy’s father

John Gore had started as a decorative painter. Specializing in heraldic designs, he developed an upper-class clientele and began to move into that class himself—as a paint merchant, a

militia officer, and eventually an Overseer of the Poor, one of the most respected

town offices. By 1770 he was considered a gentleman.

Capt. John Gore’s oldest child, Frances, married

Thomas Crafts, Jr., another decorative painter. (I suspect he was one of Gore’s early apprentices, but I can’t confirm that.) Crafts became an active member of the “

Loyall Nine” who organized the first anti-

Stamp Act protests and looked after

Liberty Tree. He, too, was rising through militia service and town offices.

Capt. Gore’s first son, also named John, became a dry goods merchant. He married the niece of the Rev.

Henry Caner, minister of

King’s Chapel. Both John, Jr., and Samuel had tried

schooling at the South Latin School, which would have prepared them for

Harvard, but decided to drop out for more practical education. Their little brother

Christopher (Kit), however, was sailing through the Latin School curriculum.

In August 1769, Capt. Gore, his son John, and his son-in-law Crafts all dined with the Sons of Liberty at

Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in

Dorchester, as

described here. At the time John, Jr., advertised that he was sticking to the

non-importation agreement in the cloth he sold from his shop.

Of course, it was hard for a paint merchant to take that stance and stay in business—the

Townshend Act put a tariff on painter’s colors. Sammy, training under his father in decorative painting, had a close-up look at that situation. In late January 1770, the

Boston Chronicle published

Customs house documents revealing that Capt. Gore had paid duties on “4 barrels Painters colours” that had arrived on the

Abigail and more goods that had later come on the

Thomas.

That revelation might have motivated the family to demonstrate their commitment to non-importation. In the third week of February, the Gores—more probably, Frances Gore and her daughters and perhaps daughters-in-law—hosted a spinning bee at their house on Queen Street. This was a social occasion, but it also showed the

women’s support for local manufacturing.

Most spinning bees took place in rural towns, usually in

ministers’ houses, with the host accepting the gift of the spun yarn to benefit the poor. Of ten spinning bees that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich counted in and around Boston in 1766-70, the Gores’ was one of only two not in a minister’s home.

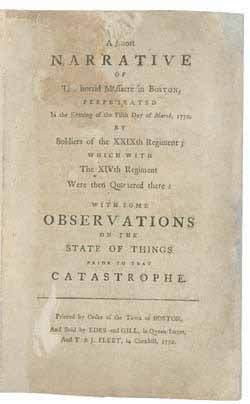

Early in its local news roundup, the 26 Feb 1770

Boston Gazette put a strong political spin on the Gores’ event:

One Day last Week a Number of Patriot Ladies met at the House of John Gore, Esq; of this Town, when their Industry at the Spinning Wheel was at least equal to any Instance recorded in our Paper.

It is principally owing to the indefatigable Pains of Mr. William Mollineux; and it will be said to his lasting Honor, that the laudable Practice of Spinning is almost universally in Vogue among the Female Children of this Town; whereby they are not only useful to the Community, but the poorer Sort are able in some Measure to assist their Parents in getting a Livelihood—

The Use of the Spinning-Wheel is now encouraged, and the pernicious Practice of Tea-drinking equally discountenanced, by all the Ladies of this Town, excepting those whose Husbands are Tories and Friends to the American Revenue-Acts; and a few Ladies who are Tories themselves.

By the time that item was published, Sammy Gore had made his own political statement about non-importation by showing up outside Ebenezer Richardson’s house on 22 February. We don’t know if he was among the boys who organized the demonstrations at

Theophilus Lillie’s shop or if he

threw garbage and rocks at Richardson’s house. But we do know Sammy Gore was close enough to the front of the crowd to be struck by pellets from Richardson’s gun.

The

Boston Gazette stated, “A youth, son to Captain John Gore, was also wounded in one of his hands and in both his thighs.” The

Boston Evening-Post reported:

Dr. [Joseph] Warren likewise cut two slugs out of young Mr. Gore’s thighs, but pronounced him in no danger of death, though in all probability he will lose the use of the right forefinger, by the wound received there, much important to a youth of his dexterity in drawing and painting.

As it turned out, Samuel Gore would enjoy a long and healthy career as a painter and manufacturer. In the 1830s a Boston barber recalled that he would show young people his scarred fingers and describe how he’d been wounded in the Revolution “with some relish.”

(For more about Samuel Gore’s Revolutionary activities and reminiscences,

see The Road to Concord.)

TOMORROW: A grand funeral.