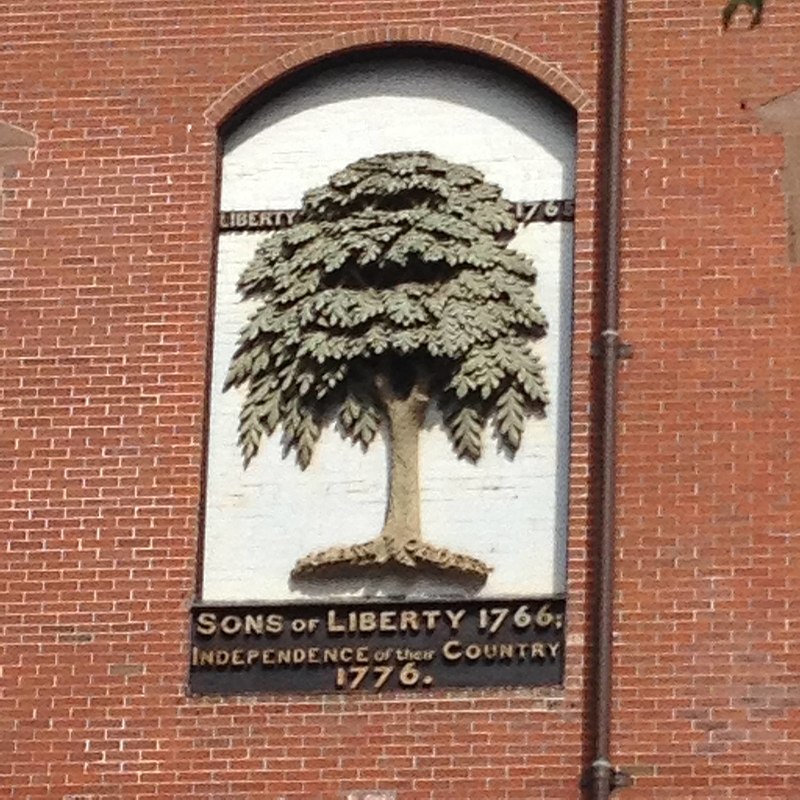

Dinner at the Sign of Liberty Tree

On 14 Aug 1769, 250 years ago today, Boston’s Sons of Liberty gathered to celebrate the anniversary of the first public protest against the Stamp Act, four years earlier.

Of course, they were also celebrating what they saw as their triumph over Gov. Francis Bernard, who had sailed away from Massachusetts at the start of the month, never to return.

The celebration actually began with fourteen toasts at Liberty Tree at eleven o’clock. Those started with “The KING” and “The QUEEN and Royal Family,” moved through John Wilkes, the “Glorious Ninety-Two,” Paschal Paoli and his Corsicans, “American Manufactures,” and finally “May the 14th of August be the annual Jubilee of Americans, till Time shall be no more.”

Then the company left town. The Sons had organized dinner for more than 300 at Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in Dorchester, the Sign of Liberty Tree. [In the winter of 1775, that tavern was a crucial spot in the story of The Road to Concord.] By dining outside of Boston, the upper-class politicians guaranteed that they could control their setting and the level of festivity.

This dinner was in honor of “the Farmer”—John Dickinson, author of The Farmer’s Letters and coauthor of “The Liberty Song.” He wasn’t there. But two of his friends from Philadelphia were: his brother, Philemon Dickinson, and Joseph Reed, then secretary of the colony of New Jersey.

John Hancock’s business protégé William Palfrey made a list of 355 gentlemen at the dinner. That list included far more than Boston's political activists. The most important elected officials were all there, including some who would later be Loyalists. The town’s schoolmasters had taken the day off, as had many merchants, doctors, lawyers, and militia officers. John Adams wrote in his diary about feeling pressure to attend: “many might suspect, that I was not hearty in the Cause, if I had been absent whereas none of them are more sincere, and stedfast than I am."

Adams described the banquet setting this way:

Because the fourteen toasts before noon weren’t enough, after dinner the party drank forty-five more. This series started with the “King, Queen and Royal Family,” followed by “A Discharge of Cannon, and three Cheers.” The toasters named fourteen British politicians considered friendly to America and the historian Catharine Macaulay. They honored “The Cantons of Switzerland,” “The States General of the seven United Provinces” of Holland, and “The King of Prussia.”

Some of the after-dinner toasts delineated the Whigs’ political ideals: “Annual Parliaments,” “A perpetual Constitutional Union and Harmony between Great Britain and the Colonies,” and “Liberty without Licentiousness.” Others identified enemies: “May the detested Names of the very few Importers every where, be transmitted to Posterity with Infamy” (more cannon). And finally “Strong Halters, Firm Blocks, and Sharp Axes, to all such as deserve either.”

Evidently the diners didn’t imbibe deeply at each and every toast because Adams declared, “To the Honour of the Sons, I did not see one Person intoxicated.”

As for the subsequent entertainment, the Sons of Liberty had provided…a hatter.

TOMORROW: But not just any hatter.

Of course, they were also celebrating what they saw as their triumph over Gov. Francis Bernard, who had sailed away from Massachusetts at the start of the month, never to return.

The celebration actually began with fourteen toasts at Liberty Tree at eleven o’clock. Those started with “The KING” and “The QUEEN and Royal Family,” moved through John Wilkes, the “Glorious Ninety-Two,” Paschal Paoli and his Corsicans, “American Manufactures,” and finally “May the 14th of August be the annual Jubilee of Americans, till Time shall be no more.”

Then the company left town. The Sons had organized dinner for more than 300 at Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in Dorchester, the Sign of Liberty Tree. [In the winter of 1775, that tavern was a crucial spot in the story of The Road to Concord.] By dining outside of Boston, the upper-class politicians guaranteed that they could control their setting and the level of festivity.

This dinner was in honor of “the Farmer”—John Dickinson, author of The Farmer’s Letters and coauthor of “The Liberty Song.” He wasn’t there. But two of his friends from Philadelphia were: his brother, Philemon Dickinson, and Joseph Reed, then secretary of the colony of New Jersey.

John Hancock’s business protégé William Palfrey made a list of 355 gentlemen at the dinner. That list included far more than Boston's political activists. The most important elected officials were all there, including some who would later be Loyalists. The town’s schoolmasters had taken the day off, as had many merchants, doctors, lawyers, and militia officers. John Adams wrote in his diary about feeling pressure to attend: “many might suspect, that I was not hearty in the Cause, if I had been absent whereas none of them are more sincere, and stedfast than I am."

Adams described the banquet setting this way:

We had two Tables laid in the open Field by the Barn, with between 300 and 400 Plates, and an Arning of Sail Cloth overhead, and should have spent a most agreable Day had not the Rain made some Abatement in our Pleasures.There’s that New England non-rhotic R in how Adams spelled “awning.”

Because the fourteen toasts before noon weren’t enough, after dinner the party drank forty-five more. This series started with the “King, Queen and Royal Family,” followed by “A Discharge of Cannon, and three Cheers.” The toasters named fourteen British politicians considered friendly to America and the historian Catharine Macaulay. They honored “The Cantons of Switzerland,” “The States General of the seven United Provinces” of Holland, and “The King of Prussia.”

Some of the after-dinner toasts delineated the Whigs’ political ideals: “Annual Parliaments,” “A perpetual Constitutional Union and Harmony between Great Britain and the Colonies,” and “Liberty without Licentiousness.” Others identified enemies: “May the detested Names of the very few Importers every where, be transmitted to Posterity with Infamy” (more cannon). And finally “Strong Halters, Firm Blocks, and Sharp Axes, to all such as deserve either.”

Evidently the diners didn’t imbibe deeply at each and every toast because Adams declared, “To the Honour of the Sons, I did not see one Person intoxicated.”

As for the subsequent entertainment, the Sons of Liberty had provided…a hatter.

TOMORROW: But not just any hatter.

3 comments:

I know the Sons weren't diligent record keepers for obvious reasons, but as a descendant of someone on that list, I can't help but wonder how many of these people were dedicated members, how many were "sunshine patriots", and how many were just looking for a free meal.

This list of attendees includes a lot of men who were prominent in Boston government without being active in imperial politics—all the selectmen, not just the fervent Whigs; all the Overseers of the Poor; all the teachers (except John Lovell); Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf; and so on. That reflects the Sons' political dominance at this moment, but it doesn't necessarily indicate how men would jump when the question was whether to obey the Crown in 1774 to 1776.

To take the family I know best, Capt. John Gore, an Overseer of the Poor, attended with his eldest son, John, Jr., and eldest son-in-law, Thomas Crafts. John, Jr., advertised non-imported products around this time but died before the war began. Crafts was one of the leading Whig activists, a member of the Loyall Nine and thus possibly an organizer of this dinner. John, Sr., became a Loyalist and spent the war years in Britain, though he returned to Boston afterward.

These Sons of Liberty held their dinner in distant Dorchester in order, many historians have argued, to keep it closed and genteel, not a public festival where anyone could get a "free meal" as some celebrations on the Common had been. The main benefit of being there wasn't the food but, as John Adams's diary entry admits, being seen as supporting the Whig cause.

It's good to see that my guy, Aaron May, was apparently sticking to his guns. He also signed the non-importation agreement in 1768.

Post a Comment