In 1843, the London bookselling firm of Thomas Thorpe issued its catalogue of manuscripts for sale, “Upon Papyrus, Vellum, and Paper, in Various Languages.”

Among those items was “A large Collection of interesting Papers, formed by the late

George Chalmers, Esq., relating to New England, from 1635 to 1780, in 4 vols. folio, neatly bound in calf, £21.”

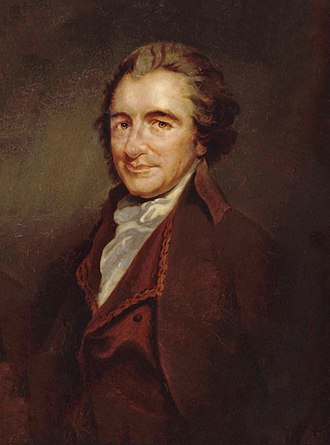

Chalmers (1742-1825, shown here) was born in Scotland and at age twenty-one settled in Maryland as a young lawyer. In early 1776 he published

Plain Truth, a point-by-point riposte to Thomas Paine’s

Common Sense. That went over so well that Chalmers soon moved back to Britain.

In 1780 Chalmers published

Political Annals of the Present United Colonies from Their Settlement to the Peace of 1763. Or rather, he published the first volume of documents about the colonial governments, tracing the history up to 1688, but never produced the second.

In 1786 Chalmers became a secretary to Britain’s privy council, and he kept that postion for decades. It provided him with the income and access he needed to collect manuscripts and write books and pamphlets about the history of Scotland, Shakespeare, other authors, controversial issues of the day, and much more.

In 1796, as Britain fought Revolutionary France, the government paid Chalmers to write a critical biography of Paine. He issued that under the pseudonym of Francis Oldys, supposedly a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania. Otherwise, he focused mainly on British topics, particularly the long history of Scotland.

Nevertheless, Chalmers’s manuscript collection shows that he never gave up on accumulating material about the old North American colonies. After his death, his papers went to a nephew, and two years after that man died in 1841, they were on the market.

Here’s a sample of what the collection included from the Revolutionary years, according to the bookseller’s catalogue:

- Various papers relating to the paper currency in the colonies, 1740-60.

- Account of the dispute at New London, at the burial of a corpse, 1764.

- List of graduates in Harvard College, who have made any figure in the world.

- Part of Mr. Otes’s speech in the general assembly at Boston, in 1768.

- Autograph letter from W. Molineux, relating to the riots at Boston, 1768.

- Letters relating to the seizure of the sloop Liberty, 1768, very curious.

- Information of Richard Silvester, of the speeches of the Boston leaders, 1769.

- Declaration of Nathaniel Coffin to Governor J. [sic] Bernard, on the designs to drive off the Governor and Lieutenant Governor, 1769.

- Key to the characters published in the Boston Chronicle of Oct. 26, 1769, (The Boston patriots characterized.)

- Autograph letter from George Mason, containing an account of the riot and attack of Mr. Mein’s house, 1769.

- Copy of a curious letter from Boston, relating to Franklin’s duplicity, &c. 1769.

- Autograph letters from John Mein and George Mason to Joseph Harrison, concerning the riot at Boston, 1769.

- Papers relating to the outrage on Owen Richards, an officer of the customs at Boston, 1770.

- Copy of a letter from Lord Dartmouth to Dr. Benjamin Franklin, about presenting a remonstrance of the court to the king, 1773.

- Account of the proceedings of Governor Hutchinson, relating to Massachusetts, &c., 52 pages, 1774.

- Account of an attack that happened on His Majesty’s troops, by a number of the people of the province of Massachusetts Bay, 1775.

It looks like Chalmers obtained many of those documents from Joseph Harrison, a Boston-based Customs official, or his estate.

Prof. Jared Sparks (1799-1866) of Harvard College must have seen the bookseller’s listing. He apparently arranged for the college library to buy some of Chalmers’s papers in 1847 while he bought others for himself, leaving them to the library on his death. Thus, the papers listed above are now at the Houghton Library and digitized as part of the university’s Colonial North America project.