Colonel Louis, Caesar Marion, and More

The Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site has posted Dr. Benjamin Pokross’s article “General Washington in the Native Northeast.” It begins:

It had been ten days since the Caughnawaga Mohawk men had arrived at the camp in Cambridge with their wives and families, and George Washington was still not sure what he was going to do. This was the second time that one of their leaders, Atiatoharongwen (also known as Col. Louis Cook), had come to Cambridge, and he had again made it known that he could raise four or five hundred men to fight for the colonists if he was given a commission in the Continental Army. But Washington was unsure how he would pay for all these additional soldiers if Atiatoharongwen did what he said, and even more apprehensive about the idea of engaging Indigenous allies at all. At least it had stopped snowing on the clear, cold, morning of January 31, 1776; this was the day Washington had promised to meet the Mohawk delegation outside.At the HUB History podcast, Jake Sconyers shared an episode on “The Well Known Caesar Marion.”

Washington’s “Out-Door’s Talk”, as he called the subsequent conversation in a letter to General Phillip Schuyler, would be the most extensive of several interactions with Indigenous people he had had while he lived in the Vassall House. These visits did not result in decisive alliances or enduring treaties. They matter, however, for two reasons. The first is that they emphasize how the Revolution—normally thought of as a conflict between American colonists and the British—occurred on Native land, in areas that had long been stewarded by Indigenous communities and where Native people continued to find ways to survive in spite of colonial upheaval. Secondly, these visits highlight the unsettled and transitional character of the very early days of the Revolution. For both Washington and the Native diplomats who came to visit him, this was a moment of experimentation, of exploring what a possible relationship between the Continental Army and Indigenous Nations could look like.

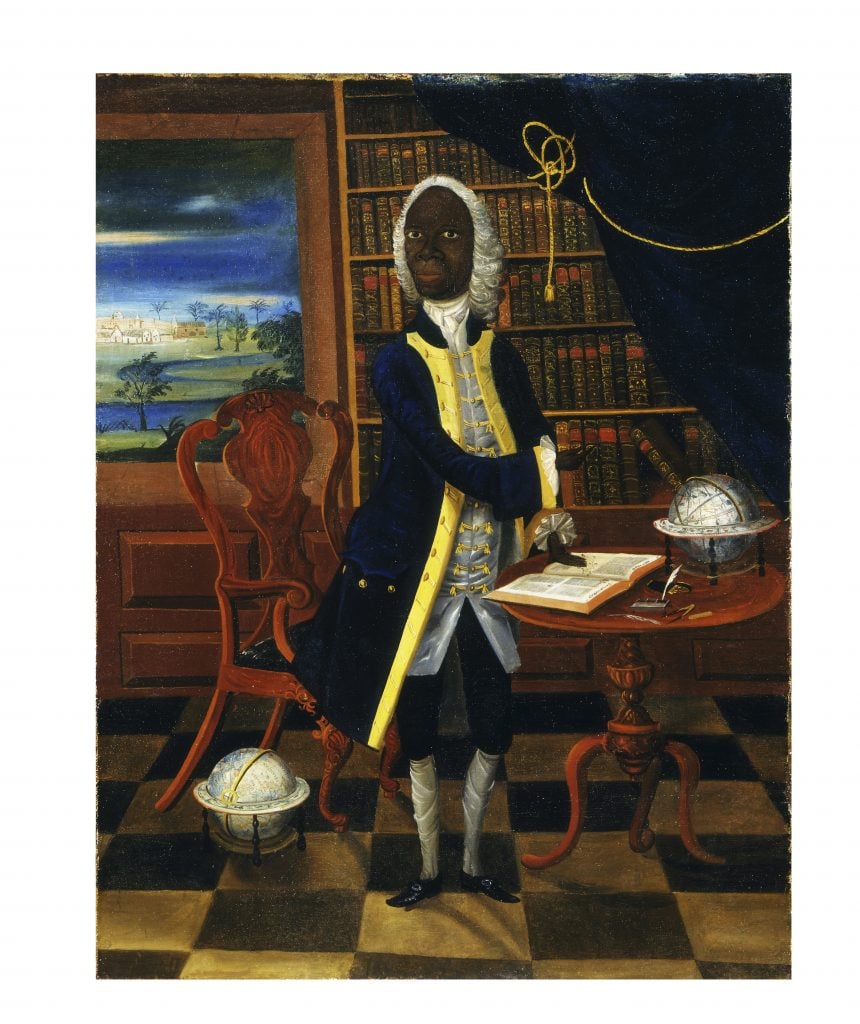

In this somewhat brief episode, we’re going to look at why Mr. Marion was thrown into Boston’s notorious jail 250 years ago this week, and then we’ll compare his treatment inside British-occupied Boston with the experience of Black volunteers in the Continental Army outside Boston, once Virginia enslaver George Washington took command.Both Pokross and Sconyers explore moments when Washington was pushed out of his comfort zone by encounters with men of color. And in both cases, while he never stopped being a planter with aristocratic ambitions, Washington was able to shift his habits and show respect for allies.

(Hearing the podcast also reminded me that I broke off a short series about Marion, promising more was “COMING UP,” nine years ago. I won’t get back to that story this week, but it’s back on my to-do list.)