Thursday, 22 Sept 1768, was not only the first day of the extralegal

Massachusetts Convention of Towns. It was also the anniversary of the coronation of

George III.

That royal holiday was accordingly observed in Boston, as the

Boston Evening-Post described:

by the firing of the Cannon at Castle William and at the Batteries in this Town, and three Vollies by the Regiment of Militia, which, with the Train of Artillery, were mustered on the Occasion.——

At the Invitation of his Excellency the Governor, his Majesty’s Health was drank at the Council-Chamber at Noon.

So much for ceremonial harmony. At that same meeting in the

Old State House, Gov.

Francis Bernard and the

Council were in a major dispute.

Three days before, the governor had formally told the Council the news that he’d leaked earlier—that

British army regiments were on the way to Boston. Under the

Quartering Act, the local authorities were required to provide housing and firewood for them. As John G. McCurdy argued at a

Colonial Society of Massachusetts session last February, we can think of the Quartering Act as one of

Parliament’s taxes on the colonies, requiring resources from local communities without their vote.

Gov. Bernard wanted the Council to start arranging to house four regiments, two on their way from

Halifax and two more to arrive later from Ireland. But the Council was determined not to cooperate. In a

report to London, Bernard claimed

James Otis, Jr., had laid out this strategy for the Whigs:

There are no Barracks in the Town; and therefore by Act of parliament they [the soldiers] must be quartered in the public houses. But no one will keep a public house upon such terms, & there will be no public houses. Then the Governor and Council must hire Barnes Outhouses &c for them; but no body is obliged to let them; no body will let them; no body will dare to let them.

The Troops are forbid to quarter themselves in Any other manner than according to the Act of parliament, under severe penalties. But they can’t quarter themselves according to the Act: and therefore they must leave the Town or seize on quarters contrary to the Act. When they do this, when they invade property contrary to an Act of parliament We may resist them with the Law on our side.

Bernard was anxious to head off such trouble. He wrote:

I answered, that they must be sensible that this Act of parliament (which seemed to be made only with a View to marching troops) could not be carried into execution in this Case. For if these troops were to be quartered in public houses & thereby mixt with the people their intercourse would be a perpetual Source of affrays and bloodsheds; and I was sure that no Commanding officer would consent to having his troops separated into small parties in a town where there was so public & professed a disaffection to his Majesty’s British Government.

And as to hiring barnes outhouses &c it was mere trifling to apply that clause to Winter quarters in this Country; where the Men could not live but in buildings with tight walls & plenty of fireplaces. Therefore the only thing to be done was to provide barracks; and to say that there were none was only true, that there was no building built for that purpose; but there were many public buildings that might be fitted up for that purpose with no great inconvenience.

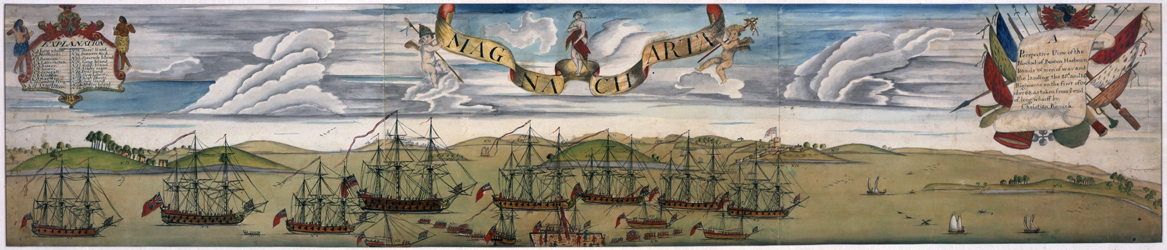

Bernard proposed that the province make the

Manufactory House available for the troops. This building had been put up in 1753 to house spinners and weavers. The province had loaned money to build it, expecting to be paid back from the profits of the cloth-manufacturing enterprise. The scheme never made money, the businessmen behind it defaulted on the loan, and Massachusetts was left with ownership of this big building near the center of town.

The Council formed a committee led by

James Bowdoin to consult with Boston’s

selectmen about the troops. On 22 September, the day of the toasts to the king, that committee reported that the selectmen “gave it for their Opinion that it would be most for the peace of the Town that the two regiments expected from Halifax should be quartered at the Castle.”

That was a new strategy, avoiding confrontations with the soldiers by housing them in the barracks on Castle William—which was on an island in the harbor. Of course, that meant those troops couldn’t patrol Boston and protect

Customs officers, which was the whole point of sending them into town. Bernard wrote, “I observed that they confounded the Words Town & Township; that the Castle was indeed in the Township of Boston but was so far from being in the Town that it was distant from it by water 3 miles & by land 7.”

The governor reproached his Council: “I did not see how they could clear themselves from being charged with a design to embarras the quartering the Kings troops.” Bernard thus hinted that the body was being disloyal to the king—and on the anniversary of his coronation! “I spoke this so forcibly,” he wrote, “that some of them were stagger’d, & desired further time to consider of it.” But one member warned the governor not to expect any progress, “pleasantly” adding, “what can you expect from a Council who are more affraid of the people than they are of the King?”

On 23 September, 250 years ago today, a smaller committee, also led by Bowdoin, was ready to present a formal report on the matter to Gov. Bernard.

Who was now at his country house out in

Jamaica Plain. This of course kept him distant from the Convention going on in

Faneuil Hall. Province secretary

Andrew Oliver told the Council “that the Weather being so stormy the Governor will not be in Town to-day, and desires they will meet him at the

Province-House to-morrow ten o’Clock, A.M.”

The next morning was stormy, too. Bernard finally came into town that Saturday afternoon to hear what the Council had to say. Which was the same thing as before, except longer: the only place for the troops was out at Castle William. After cleaning up some errors in their report, the Council had it published in the newspapers on 26 September, making the dispute a public matter.

COMING UP: Meanwhile, back in Faneuil Hall.