As I

discussed yesterday, despite how

Josiah Quincy characterized the situation in his biography of

Samuel Shaw, the Shaw family was not forced to host British

marine officers under the

Quartering Act.

Rather, in all likelihood, the merchant

Francis Shaw (1721–1784) chose to rent rooms to Maj.

John Pitcairn, Lt.

John Ragg, and perhaps other men.

We don’t have enough sources about Francis Shaw to know what his motivations might have been: money, a sense of obligation or deference to the military, a wish to mollify the royal authorities?

Shaw wasn’t a

Loyalist. He didn’t sign either of the addresses to the royal governors in 1774, nor leave town at the

evacuation in 1776. In preceding years, he hadn’t stood up to complain about any of the Whigs’ measures.

Nor, however, was Francis Shaw an active Patriot. He had joined the Boston Society for Encouraging Trade and Commerce back in the early 1760s. That was an early chamber of commerce, speaking for the merchant community, and it opposed the Sugar Act and what its members saw as overeager enforcement of that

law. In 1770 the Boston

town meeting added Shaw’s name to a committee to promote

non-importation, particularly by not selling

tea.

But other than those moments, the name of Francis Shaw doesn’t appear in connection with Whig politics. He didn’t dine with the Sons of Liberty in 1769. He wasn’t on the committee to promote the Continental Association of 1774. (He may have been a member of the St. Andrew’s Lodge of

Freemasons, meaning he knew some Whig leaders, but wasn’t forward in supporting them. Or that Freemason might have been Francis Shaw, Jr.)

The town meeting elected Shaw as a

fireward in the North End in 1772. The North End

Caucus endorsed his reelection the next year, and he kept at that job until 1784. Boston thanked him for his long service a few months before he died. But that was an apolitical job.

My impression is that Francis Shaw chose to stay out of the larger debate. His son Samuel, in contrast, was fervent for the Patriot cause in 1775. We can see hints of that difference in the anecdote about Samuel getting into an argument with Lt. Ragg,

quoted back here.

Francis Shaw had chosen to host British marine officers. The anecdote suggests he didn’t speak out against Ragg calling Americans “cowards and rebels” and then apparently moving toward a duel with twenty-year-old Samuel. The father didn’t, for instance, demand that his tenant leave his son alone—or if he did, it didn’t become part of the family lore. It was up to Maj. Pitcairn to calm matters.

Furthermore, I think the evidence suggests Francis Shaw told his son not to join the

Continental Army. Only on his twenty-first birthday, when he was no longer legally under his father’s control, did Samuel leave Boston and seek a commission in the

artillery regiment.

Once that happened, letters show that Francis Shaw supported his son, financially and otherwise. After the siege, the merchant served on Boston committees to collect taxes and record citizens’ military service. He may have invested a bit in

privateers (or this could have been a man of the same name from

Salem). In sum, Francis Shaw became a Patriot, even if he didn’t start out as one.

COMING UP:

Lt. Ragg’s war.

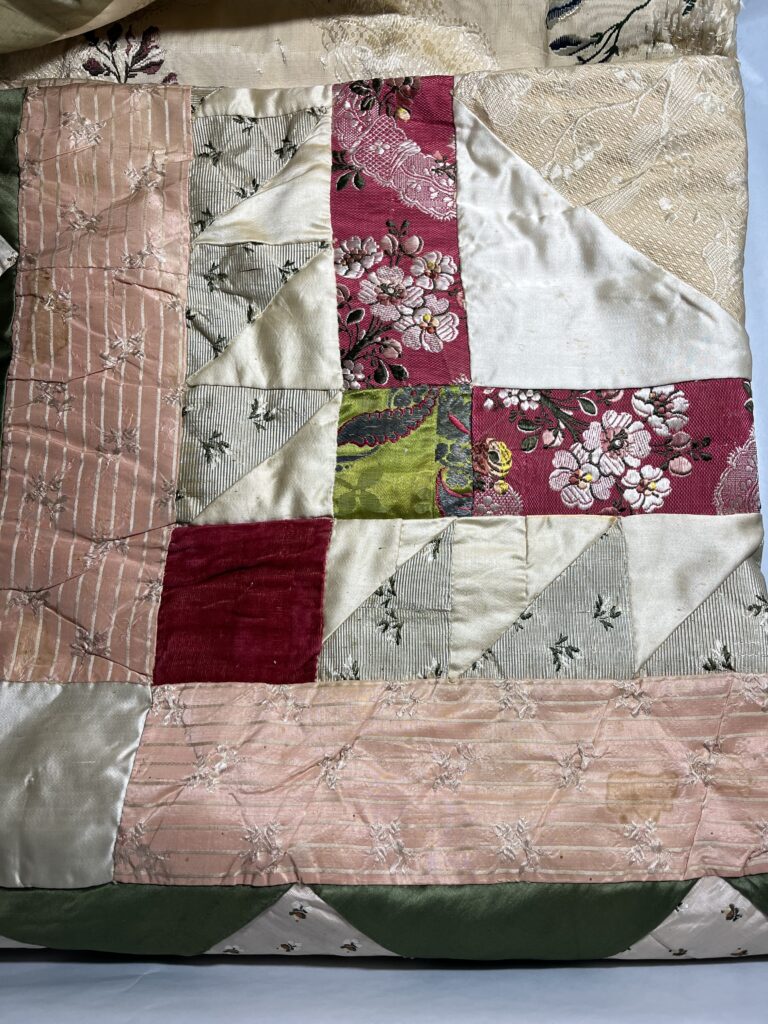

(The picture above,

courtesy of Old North, shows a sampler made by twelve-year-old Lydia Dickman in 1735. Nine years later she married Francis Shaw. They had one child together, but Lydia died in 1746 and her son the following year. Francis Shaw remarried and had more children, including Samuel. The sampler is now in the

collection of the National Museum of American History.)