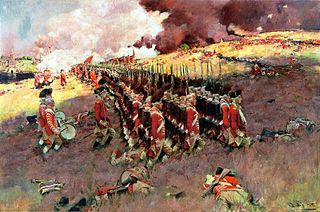

Two Lieutenants and the Battle of Bunker Hill

Lt. John Ragg of the Royal Navy’s marines entered our scene back here, in an anecdote from the Shaw family of Boston about how he got into an affair of honor with twenty-year-old Samuel Shaw.

I suspect that conflict happened before the war began, while Ragg, Maj. John Pitcairn, and perhaps other officers were boarding with the Shaw family in the North End.

It definitely happened before the Battle of Bunker Hill because Pitcairn died of his wounds that day, and the anecdote credited him with mediating the dispute.

By the date of that battle, Lt. Ragg had gotten into another argument, this time with one of his fellow British officers.

Lt. John Clarke was a veteran marine, having “served thirty six years with great credit” according to Adm. Samuel Graves. That said, Clarke had become a second lieutenant only in 1757 and a first lieutenant in 1771 (with a brief retirement on half-pay in between). He was assigned to H.M.S. Falcon.

According to British military documents that Allan French quoted in an article for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, on the evening of 19 April (i.e., the day the war began) Clarke got drunk.

Lt. Clarke was arrested “for being very much in Liquor and unfit for Duty on the Morning of the 20th of last April, for breaking his Arrest, and for grossly abusing and challenging Lieutenant John Ragg of the Marines to fight.”

On 7 June, Graves wrote, Clarke was “tried and dismissed for being in Liquor upon duty on the 19th of April last.” The admiral ordered the former lieutenant back to England.

Then, on 17 June, came the big battle in Charlestown. Lt. Ragg’s grenadier company was in the thick of the fight. Gen. Thomas Gage’s report included this casualty list from the first battalion of marines:

Not being in the Battle of Bunker Hill, or even in the British military at the time, didn’t stop Clarke from publishing An Authentic and Impartial Narrative of the Battle when he arrived back in London. That short book, credited to “John Clarke, First Lieutenant of Marines,” was one of the first descriptions of the battle to reach print and went through a second edition in London before the end of the year.

Many historians have tried to rely on Clarke’s Narrative, which offered details not found elsewhere, like Gen. William Howe’s speech to his soldiers and a description of Dr. Joseph Warren’s death. But ultimately most authors realized that Clarke was just piecing stuff together and making it up. French concluded, “it seems likely that it was written to relieve the tedium of his voyage to London, from such material as he could gather from his own observations and from the talk of the ship’s company.”

Despite his dispute with Ragg, Clarke described the first battalion of marines “behaving remarkably well, and gaining immortal honour, though with considerable loss, as will appear by the number of the officers killed and wounded.”

TOMORROW: Lt. Ragg, back in the fight.

I suspect that conflict happened before the war began, while Ragg, Maj. John Pitcairn, and perhaps other officers were boarding with the Shaw family in the North End.

It definitely happened before the Battle of Bunker Hill because Pitcairn died of his wounds that day, and the anecdote credited him with mediating the dispute.

By the date of that battle, Lt. Ragg had gotten into another argument, this time with one of his fellow British officers.

Lt. John Clarke was a veteran marine, having “served thirty six years with great credit” according to Adm. Samuel Graves. That said, Clarke had become a second lieutenant only in 1757 and a first lieutenant in 1771 (with a brief retirement on half-pay in between). He was assigned to H.M.S. Falcon.

According to British military documents that Allan French quoted in an article for the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, on the evening of 19 April (i.e., the day the war began) Clarke got drunk.

Lt. Clarke was arrested “for being very much in Liquor and unfit for Duty on the Morning of the 20th of last April, for breaking his Arrest, and for grossly abusing and challenging Lieutenant John Ragg of the Marines to fight.”

On 7 June, Graves wrote, Clarke was “tried and dismissed for being in Liquor upon duty on the 19th of April last.” The admiral ordered the former lieutenant back to England.

Then, on 17 June, came the big battle in Charlestown. Lt. Ragg’s grenadier company was in the thick of the fight. Gen. Thomas Gage’s report included this casualty list from the first battalion of marines:

1st battalion marines. — Major Pitcairn, wounded, since dead; Capt. Ellis, Lieut. Shea, Lieut. Finnie, killed; Capt. Averne, Capt. Chudleigh, Capt. Johnson, Lieut. Ragg, wounded; 2 sergeants, 15 rank and file, killed; 2 sergeants, 55 rank and file, wounded.While Lt. Ragg recovered from his wound, former lieutenant Clarke traveled back to London on H.M.S. Cerberus, which also carried Gage’s report.

Not being in the Battle of Bunker Hill, or even in the British military at the time, didn’t stop Clarke from publishing An Authentic and Impartial Narrative of the Battle when he arrived back in London. That short book, credited to “John Clarke, First Lieutenant of Marines,” was one of the first descriptions of the battle to reach print and went through a second edition in London before the end of the year.

Many historians have tried to rely on Clarke’s Narrative, which offered details not found elsewhere, like Gen. William Howe’s speech to his soldiers and a description of Dr. Joseph Warren’s death. But ultimately most authors realized that Clarke was just piecing stuff together and making it up. French concluded, “it seems likely that it was written to relieve the tedium of his voyage to London, from such material as he could gather from his own observations and from the talk of the ship’s company.”

Despite his dispute with Ragg, Clarke described the first battalion of marines “behaving remarkably well, and gaining immortal honour, though with considerable loss, as will appear by the number of the officers killed and wounded.”

TOMORROW: Lt. Ragg, back in the fight.

3 comments:

You may have mentioned this elsewhere, but promotion in the Marines (who, dear readers, were not Royal Marines until 1802) was agonizingly slow, done on seniority alone, in most cases. There was no system of purchase of commissions as the Army understood it. One had to be nominated by a person of influence to become an officer in the Marines, and, once in, there were few places to advance to, unless one wanted to spend time very far away. And even so, lieutenants would languish for decades before a captaincy opened up.

Thanks for adding that valuable detail. I’m more interested in the time between when Clarke said he started his service to the Crown, which would have been about 1740, and when he became a second lieutenant in the marines in 1757. Was he at a lower rank? In a different service?

Incidentally, John Ragg had been appointed a lieutenant in the marines in 1762, which may give some idea of his age.

In the Colonial Society of Massachusetts paper I linked to, Allan French made a big deal about John Clarke being the translator of an edition of a treatise by Vegetius, a Roman officer. That would have implications about his education, intelligence, and class.

However, in 2017 Michael King Macdona published an article in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research showing that another John Clarke, one who had become a captain in the early 1770s, was that translator.

That leaves us with even less information about the John Clarke who published on the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Post a Comment