The Continentals from the Lower Counties

From the start of nationhood Americans have spoken of the “thirteen colonies,” but really it was more like twelve and a half.

The Penn family were proprietors of both Pennsylvania and Delaware and always appointed the same man to govern both.

Though Delaware had an older history of European settlement, Pennsylvania became much bigger and wealthier. The “Lower Counties on the Delaware” had their own legislature, but many people treated that area as a mere adjunct.

Delaware didn’t rate its own part of the “Join, Or Die.” snake that Benjamin Franklin printed in 1754, for example. (Though I should also note that all of New England was one piece.)

Under the Stamp Act, the British government appointed John Hughes to collect the tax in both Pennsylvania and Delaware.

The First Continental Congress’s Articles of Association in 1774 still referred to “the three lower counties of Newcastle, Kent and Sussex on Delaware,” as did the Second’s commission for a commander-in-chief in 1775.

We might say that Delaware made itself a full-fledged state by participating in the American resistance. The three counties sent representatives to the Stamp Act Congress and then the Continental Congresses. Deriving their authority from the people through a legislature meant those men were separate from the Pennsylvania delegation. By late 1775, John Adams was writing of “Thirteen Colonies.”

Delaware also raised its own troops to support the Continental Army in January 1776. Not many, since it was a small colony: about 800 men in one big regiment under Lt. Col. John Haslet. In the summer of 1776 those Delaware Continentals marched north to New York.

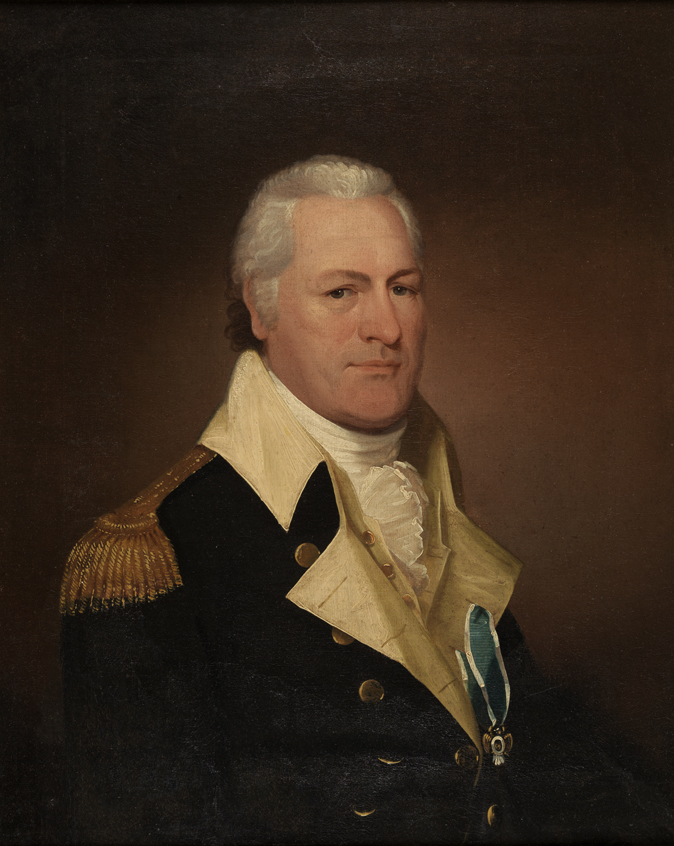

One young officer in that regiment was Lt. William Popham (1752–1847, shown above). He arrived in New York City on 21 August, and a few days later the Delaware Continentals crossed to Long Island. They were grouped with Marylanders under Gen. Stirling.

A few days later, Popham wrote:

One more thing about the Delaware regiment: They wore blue coats with red facings, not unlike the Hessians.

TOMORROW: Two lieutenants meet.

The Penn family were proprietors of both Pennsylvania and Delaware and always appointed the same man to govern both.

Though Delaware had an older history of European settlement, Pennsylvania became much bigger and wealthier. The “Lower Counties on the Delaware” had their own legislature, but many people treated that area as a mere adjunct.

Delaware didn’t rate its own part of the “Join, Or Die.” snake that Benjamin Franklin printed in 1754, for example. (Though I should also note that all of New England was one piece.)

Under the Stamp Act, the British government appointed John Hughes to collect the tax in both Pennsylvania and Delaware.

The First Continental Congress’s Articles of Association in 1774 still referred to “the three lower counties of Newcastle, Kent and Sussex on Delaware,” as did the Second’s commission for a commander-in-chief in 1775.

We might say that Delaware made itself a full-fledged state by participating in the American resistance. The three counties sent representatives to the Stamp Act Congress and then the Continental Congresses. Deriving their authority from the people through a legislature meant those men were separate from the Pennsylvania delegation. By late 1775, John Adams was writing of “Thirteen Colonies.”

Delaware also raised its own troops to support the Continental Army in January 1776. Not many, since it was a small colony: about 800 men in one big regiment under Lt. Col. John Haslet. In the summer of 1776 those Delaware Continentals marched north to New York.

One young officer in that regiment was Lt. William Popham (1752–1847, shown above). He arrived in New York City on 21 August, and a few days later the Delaware Continentals crossed to Long Island. They were grouped with Marylanders under Gen. Stirling.

A few days later, Popham wrote:

I marched toward the ground occupied by our army, in the summit of the high ground in front of Gowanus, near the edge of the river, where the enemy were landing from their ships, one or two lying near the shore to cover the landing. Many shots were exchanged between us and the enemy.The British and Hessians began to spread out and march toward the American positions. Haslet saw how “the enemy began to send detachments as scouts on our left.” Though the Continentals held the high spots, the Crown forces outnumbered them and might try to outflank them.

About 12 o’clock Gen. Stirling came to the east brow of the hill and ordered the Delaware regiment up. Here we received the first order to load with ball, and take care that our men (who were awkward Irishmen and others) put in the powder first.

We then marched up and joined the army which was drawn up in line, my regiment and my company on the left. The whole bay was covered with the enemy’s shipping. The firing continued all the time of the enemy’s landing, and we lost several men.

One more thing about the Delaware regiment: They wore blue coats with red facings, not unlike the Hessians.

TOMORROW: Two lieutenants meet.

No comments:

Post a Comment