Copy of the Proposed New Constitution for Sale in North Carolina

At the end of the Constitutional Convention, that body sent its report to the Confederation Congress, then meeting in New York. That report took the form of the draft constitution.

The Congress accepted that report and had 100 copies printed on 28 Sept 1787. Charles Thomson, the Congress’s secretary, sent official copies to the states with the invitation to convene ratification conventions.

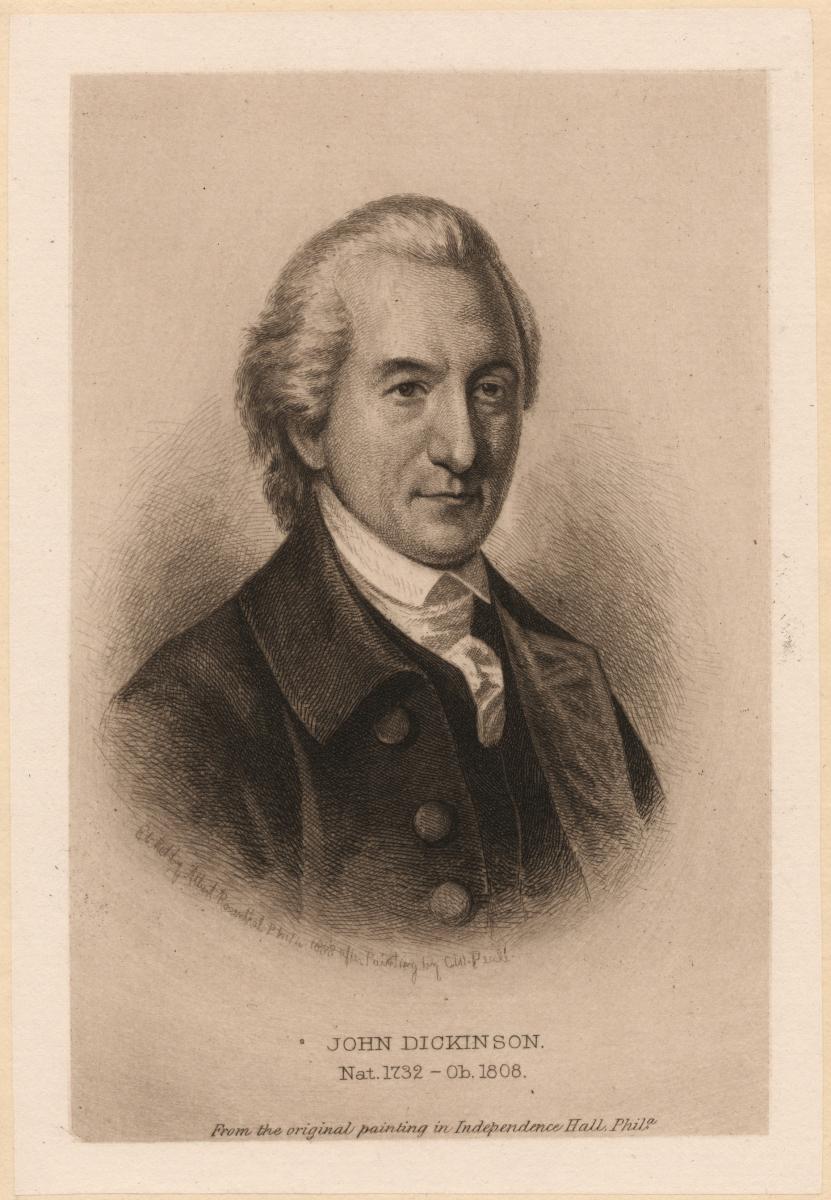

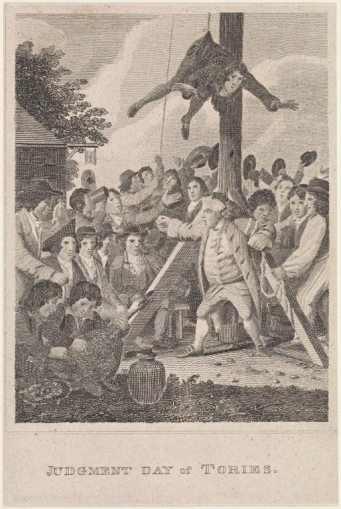

In North Carolina, Gov. Samuel Johnston presided over a convention in Hillsborough from 21 July to 4 August 1788. In the end they voted 184 to 84 to…reach no decision. The Anti-Federalist contingent insisted on a Bill of Rights, among other things. But they weren’t ready to reject the document outright.

All of the other states but Rhode Island did approve the new Constitution, however—some linking that approval to a Bill of Rights (saying “yes as long as…” rather than “no unless…”). The new federal government formed with only eleven states participating.

On 10 May 1789, Gov. Johnston and the North Carolina Council approved an address to George Washington, congratulating him on becoming President. That letter expressed hope that Congress would start the process of adding to the Constitution to “remove the apprehensions of many of the good Citizens of this State for those liberties for which they have fought and suffered in common with others.”

Washington was too ill to reply right away, but on 19 June he wrote back that he was “impressed with an idea that the Citizens of your State are sincerely attached to the Interest, the Prosperity and the Glory of America.”

In a letter to Rep. James Madison, Johnston responded, “Every one is very much pleased with the President’s answer to our Address. I have agreeably to your Wishes published them…” The exchange appeared in the State Gazette of North Carolina and in a broadside.

On 25 September, Congress approved twelve amendments to the Constitution. In November, North Carolinians gathered for another discussion of ratification, once again under Gov. Johnston. Public opinion had swung in favor of the new form of government, or at least not being left out of it. This time the vote was 194 to 77 for the Constitution.

Johnston then resigned as governor to become one of North Carolina’s first two U.S. Senators. On leaving Congress in 1793, he moved to another plantation, leaving his Hayes Farm in the hands of his son, James Cathcart Johnston. While having children with an emancipated mistress, Johnston never married, and in 1865 he bequeathed the property to his friend Edward Wood.

In recent years the Wood descendants started the process of turning that estate into a public historic site. In 2022, people cleaning the house looked through a file cabinet and found:

- A copy of the printed Constitution signed by Thomson and evidently sent to North Carolina. This is one of only seven such copies known and the only one in private hands. The last time a copy was sold was in 1891.

- A 1776 printing of the proposed Articles of Confederation.

- A printing of the proceedings of the Hillsborough Convention, the one that rejected the Constitution.

- A copy of the broadside promulgating North Carolina’s letter to Washington and the new President’s reply.