Who Should Pay for Mr. Molineux’s Cannon?

I’m at last getting to the original purpose of the 3 Feb 1775 petition to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress’s committee of safety that I’ve been discussing.

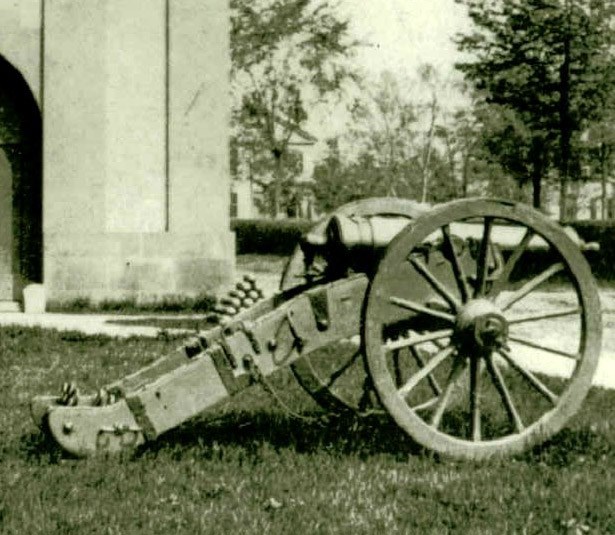

All four men who signed the petition were delegates to the provincial congress that started meeting in Cambridge on 1 February. After explaining that their towns had undertaken to mount and equip eight iron cannon obtained by William Molineux inside Boston in the fall of 1774, they wrote:

This example wasn’t about poor people needing relief or roads having to be mended, but about preparation for war. Yet the principle was the same. As long as the provincial congress was going to spend money on weapons, shouldn’t it also cover “the Expence of equiping Said Cannon for Service”?

The committee of safety actually met at Ebenezer Stedman’s tavern in Cambridge that day and came to some decisions about the provincial artillery. However, the only specific actions placed on the committee’s records involve the four brass cannon hidden at Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in Dorchester. (Yes, those are the Four Stolen Cannon at the center of The Road to Concord.)

The men of Watertown were hoping for a positive response to the petition. On 6 February, the town meeting voted “that the Committe appointed to mount ye great Guns do not Compleat the Same till after the Congress Rises.” On 11 February the congress took up the question of how its committees should handle military supplies, but four days later it decided to defer that decision until the next session at Concord in late March. On 20 February, the Watertown voters gave up waiting and decided “that the Committe appointed to mount the Great Guns Compleat the Same as Soon as may be.”

The delay and uncertainty had consequences. As of 21 February, committee of safety member Dr. Benjamin Church secretly reported to Gen. Thomas Gage, “Gun Carriages are making at Water Town by McCurtain—an Irishman, who has fallen out with the Select Men there, as he will not permit them to be taken away untill the Cash is forthcoming.”

It’s not clear to me who came up with the necessary cash. But starting on 23 February, the joint committee of safety and supplies became more involved in managing the nascent artillery force. It appointed officers and divvied out guns.

Among other things, the committee directed “That eight field pieces, with the shot and cartridges, and two brass morters with their bombs, be deposited at Leicester,” just west of Worcester, with militia colonel Joseph Henshaw. Those might be the same eight cannon that the towns of Watertown, Concord, Lexington, and Weston had been working on, or they might be eight other cannon. There were dozens being quietly moved around Massachusetts in those months.

TOMORROW: Ready for war?

All four men who signed the petition were delegates to the provincial congress that started meeting in Cambridge on 1 February. After explaining that their towns had undertaken to mount and equip eight iron cannon obtained by William Molineux inside Boston in the fall of 1774, they wrote:

Since which the late Congress held [in] Cambridge have Agreed to to [sic] provide Warlike Stores, &c, at the Expence of the provinceIn other words, this petition is rather similar to what sometimes seems like the majority of correspondence among towns and other governmental bodies in colonial New England—trying to get someone else to pay for something.

Wherefore the Inhabitants of Said towns think it Reasonable that the Expence of equiping Said Cannon for Service Should be borne in the Same manner as other Supplys and Desire yould Consider the matter & act thereon [as] you Shall think proper

This example wasn’t about poor people needing relief or roads having to be mended, but about preparation for war. Yet the principle was the same. As long as the provincial congress was going to spend money on weapons, shouldn’t it also cover “the Expence of equiping Said Cannon for Service”?

The committee of safety actually met at Ebenezer Stedman’s tavern in Cambridge that day and came to some decisions about the provincial artillery. However, the only specific actions placed on the committee’s records involve the four brass cannon hidden at Lemuel Robinson’s tavern in Dorchester. (Yes, those are the Four Stolen Cannon at the center of The Road to Concord.)

The men of Watertown were hoping for a positive response to the petition. On 6 February, the town meeting voted “that the Committe appointed to mount ye great Guns do not Compleat the Same till after the Congress Rises.” On 11 February the congress took up the question of how its committees should handle military supplies, but four days later it decided to defer that decision until the next session at Concord in late March. On 20 February, the Watertown voters gave up waiting and decided “that the Committe appointed to mount the Great Guns Compleat the Same as Soon as may be.”

The delay and uncertainty had consequences. As of 21 February, committee of safety member Dr. Benjamin Church secretly reported to Gen. Thomas Gage, “Gun Carriages are making at Water Town by McCurtain—an Irishman, who has fallen out with the Select Men there, as he will not permit them to be taken away untill the Cash is forthcoming.”

It’s not clear to me who came up with the necessary cash. But starting on 23 February, the joint committee of safety and supplies became more involved in managing the nascent artillery force. It appointed officers and divvied out guns.

Among other things, the committee directed “That eight field pieces, with the shot and cartridges, and two brass morters with their bombs, be deposited at Leicester,” just west of Worcester, with militia colonel Joseph Henshaw. Those might be the same eight cannon that the towns of Watertown, Concord, Lexington, and Weston had been working on, or they might be eight other cannon. There were dozens being quietly moved around Massachusetts in those months.

TOMORROW: Ready for war?