“The Revolution belongs to all Americans”

The New Republic just published Neem’s essay “Unfit to Lead: Trump Is the Enemy of the American Revolution.”

Here are some passages:

Today, as we approach the Declaration of Independence’s semiquincentennial, Donald Trump and his allies claim the Revolution for themselves. They have made fealty to the American Revolution part of their culture war against “woke” progressivism. The Revolution has become a pawn in Trump’s politics of retribution against the country’s supposed cultural enemies. Trump and his allies claim to be patriots while regularly violating the principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence and undermining the government established by our Constitution. . . .The New Republic article on the web has links to show some of the events Neem refers to.

For Trump, [Chief Justice John] Roberts, and their allies, the actual principles of the Revolution matter less than its capacity to signify tribal loyalty by distinguishing “real Americans” from domestic enemies. Trump conflates respect for the Revolution with loyalty to him. The gross spectacle of Trump hosting a military parade on his birthday—as do kings and dictators—and connecting it to the birth of the Continental Army illustrates all too well that he seeks to legitimize his own rule by wrapping himself in the Revolution.

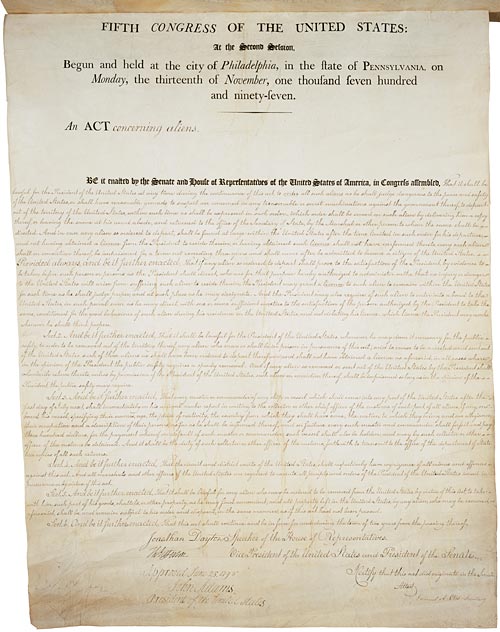

To our Founders, there was a causal relationship between legislative consent and liberty. Today, we often think freedom is the ability to do what one wants. To our Founders, in contrast, freedom was a collective possession, not a private one. Freedom was only possible in a free state in which the people or their representatives actively made the rules that govern their shared life. . . .

Trump’s violations of the Constitution are too long to list here, but among them are illegally suspending laws and violating court orders. He has sought to dominate the other two branches of government by encouraging extralegal violence against legislators, judges, and their families. He has weaponized the Justice Department to go after his political enemies. He threatens the media, universities, and other civil society institutions that dare to question his edicts. Indeed, he seeks to destroy any person or institution that checks his will. . . .

Trump and his allies distort the past to convince their followers that respecting the American Revolution is somehow compatible with supporting a tyrant. They want to turn the Revolution into a symbol for tribal loyalty, but the Revolution belongs to all Americans. The United States was born from a revolt against lawless tyranny and arbitrary power. Today, future generations of Americans are counting on us to protect the republic. Like those who sacrificed so much to secure our freedom two and a half centuries ago, once again we Americans must pledge our sacred honor to uphold the legacy of the American Revolution from those who invoke it only to betray it.