All Roads Lead to Windham County

One claim is that the father, Francis Akley, Sr., died at the Battle of Bunker Hill. His name doesn’t appear on any of the American casualty lists, however. He would have been about fifty years old at the time, and as of September 1772 he had been admitted to the Boston almshouse and designated “Lame.” So I’m skeptical.

Similar family tradition says that the youngest brother, William, born in 1769, was killed at the Battle of Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain in 1814. I haven’t found a casualty list to address that.

Rather, the big mystery about the Akley family that I’d love to be revealed, but doubt ever will be, was how they stayed in touch.

The Akleys fell on hard times in the 1760s. The Boston Overseers of the Poor largely split up the family, sending children to far-flung towns in the province. Then came the disruption of the war.

Eventually four of the brothers applied for Revolutionary War pensions from the federal government. None of those documents described their birth family, upbringing, or other relatives not directly germane to proving their military service or need. Only one brother even mentioned being born in Boston.

Nevertheless, those pension applications offer evidence of a bond still holding the family together. Namely, all four of those brothers ended up in the same southeastern corner of Vermont.

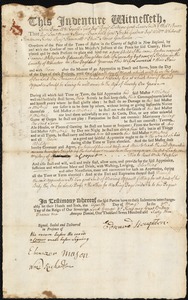

The first was Francis Akley, Jr. He was indentured to Edward Houghton of Lancaster from 1763 until he came of age in 1772. There were two Edward Houghtons in that town in the mid-eighteenth century, and I’m guessing Francis’s master was the Edward Houghton born in 1730 and married to Lucretia Richardson in 1760. He evidently moved to Holden around the time he took in Francis since the Boston Overseers of the Poor got a character reference from Lancaster but listed Houghton as coming from Holden.

In 1773 that Houghton family moved to Guilford, Vermont. This new community had had its first town meeting just the year before. It had charters from Gov. Benning Wentworth of New Hampshire in 1754 and 1764, but there was also a competing land grant from New York in 1771, and that conflict took decades to sort out. The initial slate of officials elected in 1772 included constable David Goodnough and clerk and assessor John Shepardson.

Edward Houghton died in Guilford in 1782, having achieved the militia rank of lieutenant. His widow Lucretia ran a tavern that was focus of fighting between ”Vermonters” and “Yorkers” two years later, and their sons, including another man named Edward, became prominent property-owners in the following decades.

According to Francis Akley’s pension application, he was living in Guilford, Vermont, when the war began. He had evidently followed the Houghtons north, either to continue working for them or to seek his own farmland.

In early 1776 Francis’s younger brother Thomas Akley also came to Guilford. He had grown up in Dedham and spent most of the preceding year serving in a Dedham-based company of the Continental Army. For a while that company was stationed in Roxbury. Had Thomas met Joseph Akley and his young family there when they were refugees from Boston or when Joseph was doing militia duty on the siege lines?

In any event, the only reason Thomas Akley would have traveled out to Guilford after his army service was to rendezvous with big brother Francis. In June 1776, Thomas Akley decided to go back into military service, enlisting under Guilford official John Shepardson.

Six months later, in January 1777, Francis Akley also signed up for the army. He recalled being recruited by David Goodnough, who in May 1775 had been elected as first lieutenant of Guilford’s militia company.

Thomas was in his New Hampshire regiment for a year. Francis did a longer stint as a ranger. He was at the surrender of Gen. John Burgoyne after Saratoga—and so was their younger brother John, by then drum major for a Massachusetts regiment. Did Francis and John Akley seek each other out around the surrender ceremony?

After the war all three of those brothers returned to southeastern corner of Vermont. I can’t find primary records about Francis’s family, but he was living in the town of Halifax, next to Guilford, when he applied for a pension in 1819.

Thomas settled in Brattleboro, also next to Guilford. He married Abigail Wilder in 1783, and they had several lots of children who remained in the region, spelling their surname Akeley. The photo above shows Thomas and Abigail Akley’s house when it was on the market last year.

Francis and Thomas’s younger brother John returned to the Springfield, Massachusetts, area after the war and married in Connecticut. At some point, however, he and his wife Miriam Ward joined his brothers in southeastern Vermont. According to a Ward family genealogy, they lived with their children in Brattleboro for a while before moving to Connecticut in the early 1800s.

Finally, brother Samuel Akley grew up, married, and had children in Topsham, Maine. Nonetheless, he was living in Halifax, Vermont, in 1827 when he first applied for a Revolutionary War pension. Quite possibly his older brothers’ success at getting such pay inspired him to try. Later Samuel moved back to Maine.

That pattern means these Akley brothers somehow kept in touch even though they grew up from fairly early ages in different corners of Massachusetts. Had they been able to make periodic visits back to Boston to see their parents and siblings remaining there? Were they writing back and forth the whole time? We’ll probably need to find private correspondence to know.