Searching for Revolutionary Charlotte

Fortunately for me, I was in Charlotte, away from the worst damage by wind and flooding.

After speaking at a convention, I’d planned to spend another day and a half in the Asheville area, just relaxing. Well, that became impossible.

I made new arrangements and saw more of Charlotte. In particular, I checked out the markers along what the city calls its Liberty Walk, obviously inspired by Boston’s Freedom Trail.

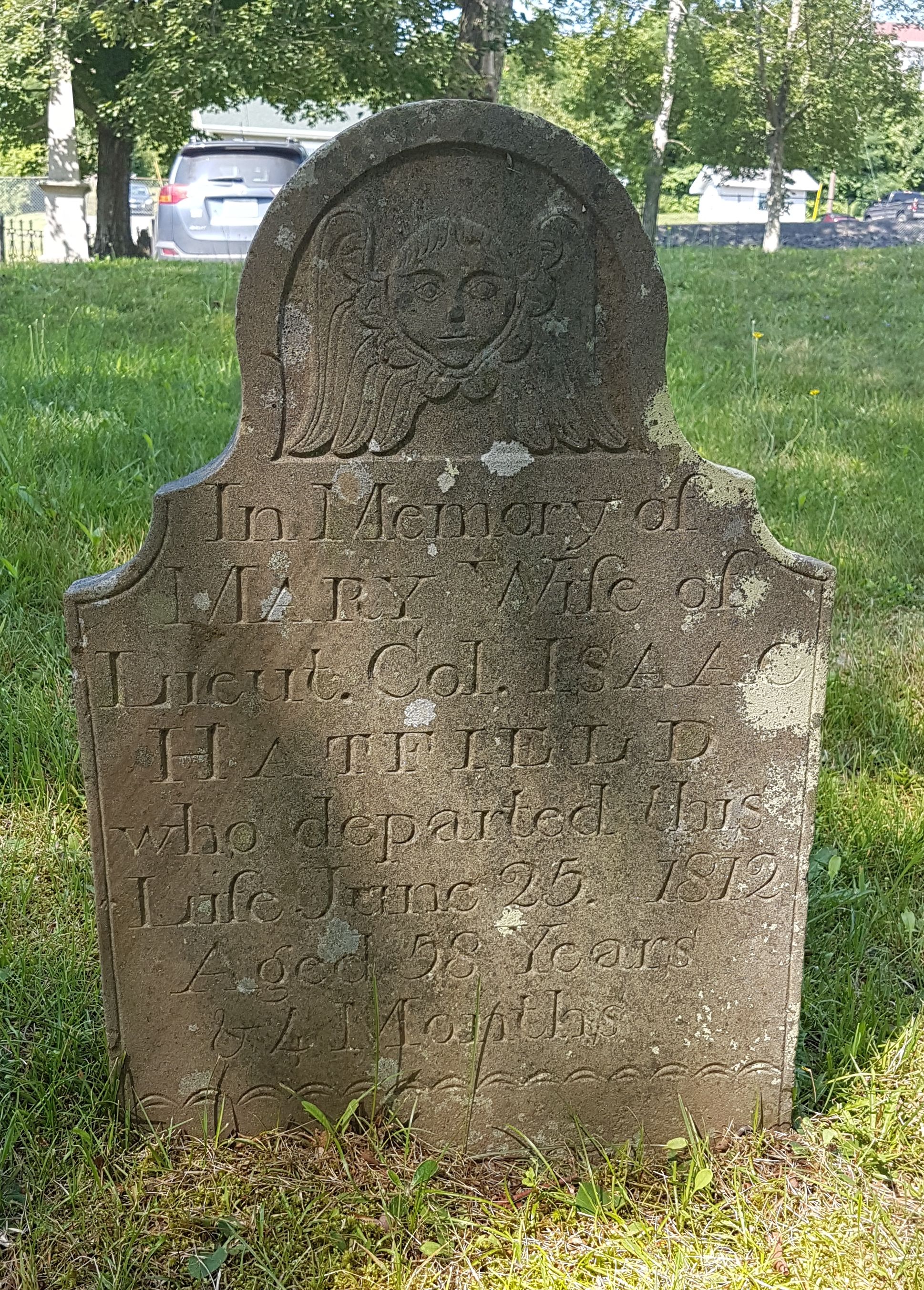

Signs, linked by tablets in the sidewalk, mark the locations of long-gone buildings and events. The walk doesn’t pass the sort of historic houses, churches, or civic structures that Boston has preserved. Instead, the city is quite new, with lots of construction and recent skyscrapers styled to recall earlier decades. To be sure, the Settler’s Cemetery, where I took the photo above, dates back to the eighteenth century.

About half of the markers along the Liberty Walk refer to one of two events:

- The Battle of Charlotte on 26 Sept 1780, in which Gen. Cornwallis’s forces seized the town after a short resistance by local militia companies under Col. William R. Davie.

- The so-called “Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.”

As for the Mecklenburg Declaration, that’s a myth that only people from North Carolina speak up for. Since it’s referred to on the state flag, though, everyone is brought up believing in it.

The strong historical consensus outside of North Carolina is that a Mecklenburg County convention on 31 May 1775 issued twenty radical resolutions, printed in newspapers that same year. There’s no historical dispute about that event, but it gets only one marker on the trail instead of several.

Imperfect memories of that gathering, tinged by later events, grew into a claim in 1819 that locals had made a full-throated declaration of independence from British government on 20 May 1775. There’s no contemporaneous documentation of that putative event. The reconstructed “Declaration” actually provides evidence that it was composed later.

The Liberty Walk has some other miscellaneous markers, such as one for a soldier of African ancestry named Ishmael Titus. However, I couldn’t find that marker, and the audio tour gave no details about what it called Titus’s “remarkable life” after he was born enslaved in 1759.

I therefore looked up information about Ishmael Titus after getting home. That webpage gives an earlier birth year and states that he lived to be about 112. In later life Titus lived in Savoy and Williamstown, Massachusetts. William Cooper Nell described him in The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. That passage and an application for a Revolutionary War pension (rejected) are the two big sources on Titus’s life, and they don’t always mesh.

Most of the stops on the Liberty Walk are just metal or stone signs, such as one reporting that Gen. Nathanael Greene took command of the Continental Army’s southern forces in Charlotte.

But there is a fully modeled, though less than full-sized, statue of Queen Charlotte with two little dogs. A main avenue through the city still bears the name of Gov. William Tryon, who moved on to New York in 1771. So the royal government still has a presence in the “Queen City.”

Also in Charlotte, the university library where I spoke displays N. C. Wyeth’s painting of Patrick Henry bathed in heavenly inspiration.