“Once cut for the Simples, but never cured”?

For example:

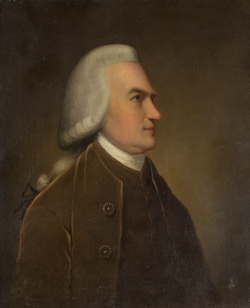

Samuel Plunder, a Senator, formerly a Receiver of the Tribute of the Parish, Master of the black Art, can cheat without a Mask of Honesty, supported by Contribution, and the Votes of a Mobb.That’s Samuel Adams, whom political opponents often criticized for his performance as a tax collector in the early 1760s.

And “Charles Spiritual, Guide and Protector of the Junto,” surely meant the Rev. Dr. Charles Chauncy, minister of the First Meeting and a close ally of the Boston Whigs.

But does that make “Samuel Tubb, private Chaplain to Simple John,” the Rev. Dr. Samuel Cooper, minister of the Brattle Street Meeting that included John Hancock, already called “John Dupe”?

That seems almost certain, but right after “Samuel Tubb” comes “John Simple, a mighty Coxcomb, very important and bigg with Nothing, well known for the Drubbings he has received.” So is “Simple John” in one sentence different from “John Simple” in the next? This “John Simple” doesn’t resemble Hancock, but who is he?

Speaking of Hancock, that “John Dupe” is called “remarkably melancholy on his Loss of Lady Beaver.” A couple of months earlier, on 22 February, the printer John Boyle wrote in his journal:

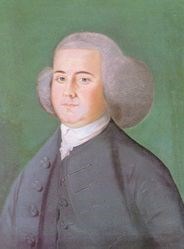

Married, Mr. Henderson Inches, Merchant, to Miss Sally Jackson, Daugh. Of Joseph Jackson, Esq.—Mr. John Hancock hath paid his addresses to Miss Jackson for about ten years past, but has lately sent her a Letter of Dismission.So was Sarah Jackson (1739–1771), shown above, courtesy of the Huntington) “Lady Beaver”? If so, does that let us interpret this entry among the characters:

Alderman Hemp, Son of the transported Cobler, well known for his great Judgment as a Politician, Chief of the grand Committee, by his wond’rous Capacity has cut off John Dupe’s Pretensions to Miss Beaver.Henderson Inches (1726–1780) was a selectman (“Alderman”?) and active on merchants’ committees. He was born in Dunkeld, Scotland, and his father, Thomas Inches, brought the family to Boston when Henderson was a child. The town meeting voted to make Thomas Inches a sealer of leather for several years in the 1730s, so was he indeed involved in making shoes? But what might “transported” have meant? And why the name “Hemp,” which first made me think of ropemaker and selectman Benjamin Austin?

And as for profiles like these:

Edward Shallow, Friend and Neighbour to Squire Lemon, once cut for the Simples, but never cured, Carrier of Intelligence, full freight’d with Absurdities.I’m at a loss.

William the Gunner, or the one ey’d Philosopher, Brother to Shallow, formerly kept a chop House in one of the Danish Islands.

William Homer, Esq; the Jew, famous for his Treatise on Cuckoldom, well known for his Humanity and publick Spirit.

TOMORROW: Did John Mein write this article?