The Paragraphs James Otis Cooked Up

In his diary John Adams described how he spent the evening of Sunday, 3 Sept 1769, in the Edes and Gill print shop: “preparing for the Next Days Newspaper—a curious Employment. Cooking up Paragraphs, Articles, Occurences, &c.—working the political Engine!”

James Otis, Jr., and Samuel Adams evidently brought the young lawyer along as they prepared propaganda for the next day’s readers. Media historians often quote that entry in discussions of how Boston’s Whig press operated.

While that writing process might have been typical, the paragraphs that the Whig leaders came up with after that particular Sabbath had unusual consequences. What Otis wrote that night broke whatever gentlemen’s truce he’d forged the day before with the Commissioners of Customs.

Three items appeared over Otis’s signature on page 2 of the 4 September Boston Gazette. At the top of the first column, labeled “ADVERTISEMENT,” was a paragraph that began:

Next was the text of an 11 August letter from Joseph Harrison, the long-time Customs Collector, denying he’d meant to “cast any person reflection or censure” on Otis in a report to his bosses. Otis had asked Commissioner Robinson about that issue on Saturday and received no answer. In the newspaper he had more to say, which I’ll quote tomorrow.

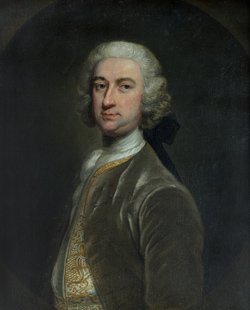

The third item consisted of extracts from a 1761 deposition by Charles Paxton (shown above) about a political alliance of rival Customs officer Benjamin Barons, the Boston merchants, and Otis. I started out to explain that issue, and after two long paragraphs I realized the most important detail in 1769 was that nobody cared. Eight or more years before, Otis reportedly was heard to “speak disrespectfully and threateningly of the Governor.” So what? Gov. Francis Bernard had left Boston under a cloud. That political fight was over. Otis had won.

As far as I can tell, the accusations Otis was responding to hadn’t appeared in any local newspaper. There were actually very few mentions of him in the Customs office documents recently leaked from London. Those few references were mostly about how he had moderated town meetings in late 1768 just before and after the arrival of the troops.

It looks to me like Otis was seeing direct accusations against him in what were at most oblique descriptions of him leading a generally obstreperous town. Furthermore, he thought it was a good idea to publicize those charges of disloyalty instead of letting them fade away. This doesn’t seem like a canny, rational political response. It seems a manifestation of the manic mood that comes through in John Adams’s other diary comments that week.

TOMORROW: How Otis lashed out verbally.

James Otis, Jr., and Samuel Adams evidently brought the young lawyer along as they prepared propaganda for the next day’s readers. Media historians often quote that entry in discussions of how Boston’s Whig press operated.

While that writing process might have been typical, the paragraphs that the Whig leaders came up with after that particular Sabbath had unusual consequences. What Otis wrote that night broke whatever gentlemen’s truce he’d forged the day before with the Commissioners of Customs.

Three items appeared over Otis’s signature on page 2 of the 4 September Boston Gazette. At the top of the first column, labeled “ADVERTISEMENT,” was a paragraph that began:

WHEREAS I have full evidence that [Commissioners] Henry Hulton, Charles Paxton, William Burch, and John Robinson, Esquires, have frequently and lately treated the character of all true North Americans in a manner that it not to be endured, by privately and publickly representing them as Traitors and Rebels, and in a general combination to revolt from Great Britain.Otis concluded by asking the government in London to “pay no kind of regard to any of the abusive misrepresentations of me or my country.” So there.

And whereas the said Henry, Charles, William, and John, without the least provocation or color, have represented me by name as inimical to the rights of the Crown, and disaffected to his Majesty…

Next was the text of an 11 August letter from Joseph Harrison, the long-time Customs Collector, denying he’d meant to “cast any person reflection or censure” on Otis in a report to his bosses. Otis had asked Commissioner Robinson about that issue on Saturday and received no answer. In the newspaper he had more to say, which I’ll quote tomorrow.

The third item consisted of extracts from a 1761 deposition by Charles Paxton (shown above) about a political alliance of rival Customs officer Benjamin Barons, the Boston merchants, and Otis. I started out to explain that issue, and after two long paragraphs I realized the most important detail in 1769 was that nobody cared. Eight or more years before, Otis reportedly was heard to “speak disrespectfully and threateningly of the Governor.” So what? Gov. Francis Bernard had left Boston under a cloud. That political fight was over. Otis had won.

As far as I can tell, the accusations Otis was responding to hadn’t appeared in any local newspaper. There were actually very few mentions of him in the Customs office documents recently leaked from London. Those few references were mostly about how he had moderated town meetings in late 1768 just before and after the arrival of the troops.

It looks to me like Otis was seeing direct accusations against him in what were at most oblique descriptions of him leading a generally obstreperous town. Furthermore, he thought it was a good idea to publicize those charges of disloyalty instead of letting them fade away. This doesn’t seem like a canny, rational political response. It seems a manifestation of the manic mood that comes through in John Adams’s other diary comments that week.

TOMORROW: How Otis lashed out verbally.

2 comments:

Dunno. Looks to me like he could be establishing his "street cred".

Starting static without your homies watching your back doesn't always end well...

Post a Comment