“To submit myself to all the orders and regulations of the army”

I, A. B. do hereby solemnly engage and enlist myself as a soldier in the Massachusetts service, from the day of my enlistment to the last day of December next, unless the service should admit of a discharge of a part or the whole sooner, which shall be at the discretion of the committee of safety; and, I hereby promise, to submit myself to all the orders and regulations of the army, and faithfully to observe and obey all such orders as I shall receive from any superior officer.Most men were already required to serve in the militia, but the committee was now thinking about “the army.”

It took until 1 May before another committee of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress came up with language for an officer’s commission:

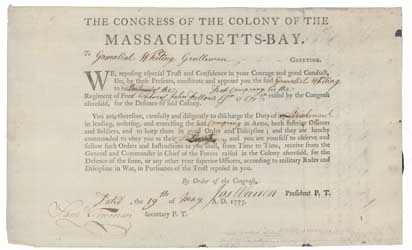

THE CONGRESS OF THE COLONY OF THE MASSACHUSETTS BAY.The congress ordered a thousand copies of that form to be printed.

To Greeting:

We, reposing especial trust and confidence in your courage and good conduct, do, by these presents, constitute and appoint you, the said to be of the regiment of foot raised by the Congress aforesaid for the defence of said colony.

You are, therefore, carefully and diligently to discharge the duty of a in leading, ordering and exercising the said in arms, both inferior officers and soldiers, and to keep them in good order and discipline; and they are hereby commanded to obey you as their ; and you are yourself to observe and follow such orders and instructions as you shall, from time to time, receive from the general and commander in chief of the forces raised in the colony aforesaid, for the defence of the same, or any other your superior officers, according to the military rules and discipline in war, in pursuance of the trust reposed in you.

By order of the Congress, the , of A. D. 1775.

The Massachusetts Historical Society shares the image of one of those forms, given to Lt. Gamaliel Whiting of Great Barrington on 19 May.

The provincial congress listed Whiting as an ensign when it issued commissions for Col. John Fellows’s regiment on 7 June. It looks like “Ensign” was scraped off and the word “Lieutenant” inserted in three places, and by August the province did list Whiting as a lieutenant.

Someone added a note to this document about an “officer resigning and leaving the company at Springfield on the march to Boston,” allowing/necessitating Whiting’s promotion. Contrary to that note, there’s no evidence he achieved another promotion to captain before the end of the year. So I think family members recalled him stepping in for another man, but they mistakenly thought that happened after this commission rather than before.

(Until recently, the webpage for this document identified it as “Appointment as lieutenant in Massachusetts militia,” but now it correctly says, “Appointment as lieutenant in Massachusetts Bay Colony Regiment of Foot.” That reflects the misconception I discussed back here, that until Gen. George Washington arrived the Americans at the siege of Boston were all militia men. We’re all working on getting that transition right!)

TOMORROW: In the neighboring colonies.