“The said Marr further declared…”

Multiple people nonetheless reported hearing Bateman as a prisoner blame the regulars for shooting first, which was definitely what his provincial captors wanted to hear. Whether he was speaking honestly, or planning to defect, or felt he had to curry favor with the local doctors to get his wound treated, that’s what he said.

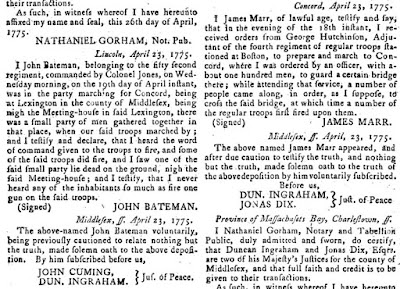

However, another captured redcoat, Pvt. James Marr of the 4th Regiment, almost certainly was at the common at the crucial time. The light infantry company of the 4th was near the front of the British column. What’s more, Marr told the Rev. William Gordon that he was part of “the advanced guard, consisting of six, besides a sergeant and corporal.”

Marr told Gordon:

They were met by three men on horseback before they got to the meeting-house a good way; an officer bid them stop; to which it was answered, you had better turn back, for you shall not enter the Town; when the said three persons rode back again, and at some distance one of them offered to fire, but the piece flashed in the pan without going off. I asked Marr whether he could tell if the piece was designed at the soldiers, or to give an alarrm? He could not say which.That matches the report of Lt. William Sutherland, riding at the head of the column. He wrote:

I went on with the front party which Consisted of a Serjeant & 6 or 8 men, I shall Observe here that the road before you go into Lexington is level for about 1000 Yards, Here we saw Shots fired to the right and left of us, but as we heared no Whissing of Balls I conclude they were to Alarm the body that was there of our approach. On coming within Gunshot of the village of Lexington a fellow from the corner of the road on the right hand Cock’d his piece at me, burnt priming…Sutherland and Lt. Jesse Adair of the marines reported this encounter to Maj. John Pitcairn, who in turn informed Gen. Thomas Gage a few days later:

When I arrived at the head of the advance Company, two officers came and informed me, that a man of the rebels advanced from those that were assembled, had presented his musket and attempted to shoot them, but the piece flashed in the pan.Pvt. Marr thus confirmed a Crown talking-point about the battle, though he probably didn’t know Gage and his officers were making a big deal about that early shot. (It’s also striking that Gordon wrote down Marr’s remark and had it published within a few weeks of the battle, even though it didn’t help his side of the conflict. He left that detail out of his History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of America, however.)

As for the shots on the Lexington common, Gordon went on:

The said Marr further declared, that when they and the others were advanced, Major Pitcairn said to the Lexington Company, (which, by the by, was the only one there,) stop, you rebels! and he supposed that the design was to take away their arms; but upon seeing the Regulars they dispersed, and a firing commenced, but who fired first he could not say.Marr’s account agrees with what a lot of British eyewitnesses described—but not with the testimony that the Massachusetts Provincial Congress published in April 1775. Those depositions, collected from provincials and Pvt. Bateman, chorused that Maj. Pitcairn had ordered the regulars to fire the first shots. In contrast, Marr said Pitcairn yelled something else, and he didn’t know which side fired first.

Marr was at the front of the British column at Lexington and thus had an excellent view of what happened. He cooperated with the magistrates collecting evidence for the congress, but his description was of no value to those Patriot authorities. As a result, they published a deposition from Marr—but about the first shots at Concord instead.