“The blood continued to dribble, for two days after”

In another book Neale identified himself as “formerly surgeon to the Duke of Northumberland’s regiment, of fifth battalion of infantry, and the Royal Hospital at Chatham.”

The Duke of Northumberland was previously Earl Percy, colonel of the 5th Regiment. The 1781 Army List names Neale (rendered as “St. John Neill”) as surgeon of that regiment, appointed November 1780. He may have previously been a surgeon’s mate, or he may have drawn from his predecessors’ accounts of what they did earlier in the war.

Chirurgical Institutes contains a description of Lt. Thomas Hawkshaw’s condition and treatment by the 5th’s medical staff after he was wounded on 19 Apr 1775.

Neale’s section labeled “History of the wound of the gallant Captain Hawkshaw.” reported:

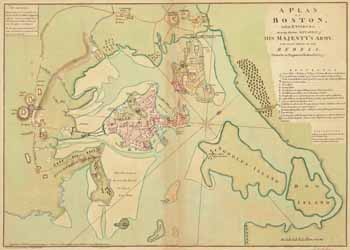

The most remarkable wound in the neck, which happened during the American war, was that of Captain Hawkshaw, of his Majesty’s 5th regiment of infantry, This gallant officer was wounded in the neck, by a musquet ball, which entered the coraco hyoideus muscle, on the right side, passing through and through behind the gullet, which it grazed in its passage.Thomas Hawkshaw was a lieutenant when he was wounded, but he was promoted to be a captain-lieutenant in the 5th Regiment in November 1777 and then captain in November 1778. Neale probably knew him by that rank. There was certainly no other officer named Hawkshaw in the regiment.

The sufferings of that brave soldier, in the course of his cure, is far above my abilities to express, which he bore with the greatest fortitude. The instant after he received his wound, the blood gushed out in torrents from his mouth and nostrils, and the wound also bled profusely. At first it was feared that the large blood vessels had suffered, but they fortunately escaped from the blow: although the ball had passed within a hair’s breadth of the COROTID ARTERIES.

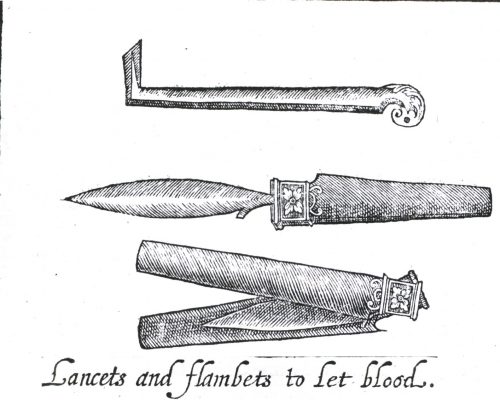

An external dilatation [stretching] was soon made, as much as the situation of the parts would admit, a soft dressing applied, and as soon as was possible, his neck covered with an emollient poultice. Soon after he was bled copiously, although he had lost a large quantity from the wound, and the blood continued to dribble, for two days after, from his mouth and nostrils.

In the evening he had a clyster [enema], and towards bed time, a few drops of laudanum, which was got down with great difficulty. He spent a restless night, and as we were fearful of a hæmorrhage, a surgeon was constantly with him. The next day all his powers of deglutition [swallowing] were impeded, so that he could scarcely get down fluids into his stomach, which was contrived to be conveyed through a small tube by suction: and the same method was used for his anodyne [painkiller] at night. The second and third night was something better than the first, but attended with considerable spasms at intervals.

On the third morning the dressings were removed, which came off with ease, from the suppuration which had taken place, and the wound dressed with warm balsamic digestives. The inflammation of the surrounding parts, was very considerable, which had communicated to both the larynx and pharynx.

From the third to the twentieth day, matters went on (all circumstances attending this extraordinary wound being considered) as well as could be expected. He was supported solely by fluids, which he sucked down through the small tube above mentioned, for the space of thirty days, sometimes cows milk, at other times panada [bread soup], with now and then a spoonful of wine.

About the end of this period, he was enabled to swallow spoon meat, but was reduced to great weakness. The peruvian bark [quinine] was now administered copiously, and in three weeks more he was enabled to get down solid food.

In another fortnight his wound was perfectly healed, and in every respect he was restored to his pristine health, to the great joy of all who were acquainted with the great merit of this brave officer.

It’s striking how these eighteenth-century military surgeons decided that a patient who just had blood gushing from his mouth, his nostrils, and a wound in his neck really needed to be “bled copiously.” And it’s a testament to Lt. Hawkshaw’s constitution that he survived.

TOMORROW: A deathbed admission?