A City Project to Reconstruct Charlestown in June 1775

Last month, on the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Boston’s Archaeology Program announced the release of research on the people who lived in Charlestown at that time.

During the battle, most of the town burned to the ground. That event provided a physical marker in the ground, and also a documentary milestone as inhabitants filed claims for their losses. However, the department notes, “Despite multiple attempts over half a century, no funds were ever granted.”

Using real estate records compiled by Thomas Bellows Wyman in The Genealogies and Estates of Charlestown (two volumes, 1879), the City Archaeology Team produced a map of property ownership in June 1775 that can be viewed here. The announcement says, “Each property is clickable, with details including a direct link to the property deed (via free familysearch.org account).”

The next step: “property descriptions based on deeds and claims documents to better understand the layout of buildings, structures, wharves, agricultural spaces, fences, and other landscape features for a future 3D landscape reconstruction of 1775 Charlestown.”

Another product of this effort is a reconstructed “census” for Charlestown in 1775, here in spreadsheet form.

Finally, there are multiple databases about the claims themselves, now housed in the Boston Public Library. Those documents have been scanned and are being transcribed, but the index is already available.

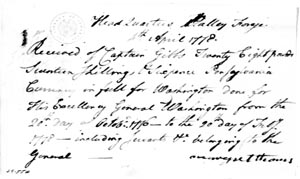

One name that stood out for researchers and myself was Margaret Thomas, filing for the loss of a house and furnishings worth £68.9, as shown here.

Was this the same Margaret Thomas who worked at Gen. George Washington’s Cambridge headquarters by February 1776, joined the general’s traveling domestic staff, and married William Lee before the end of the war? We know that other people who came to work at the commander’s headquarters in 1775–76 had been burned out of Charlestown.

The handwriting on the “Summary Accompt.” filed with the town doesn’t match the signature on a receipt Margaret Thomas signed in Valley Forge in April 1778. But it’s possible that the claim was filed by someone else on Thomas’s behalf, or that this summary was copied by someone else. It’s definitely a lead worth following up.