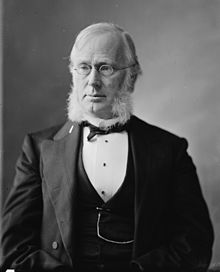

George Frisbie Hoar (1826–1904, shown here) was born in

Concord. His father, Samuel Hoar, represented the area in the U.S. Congress and

contributed to the wording of the town’s monument at the North Bridge.

In his autobiography Hoar wrote fondly about growing up in Concord, and particularly about living reminders of the Revolutionary War:

Scattered about the church were the good gray heads of many survivors of the Revolution—the men who had been at the bridge on the 19th of April, and who made the first armed resistance to the British power. They were very striking and venerable figures, with their queues and knee-breeches and shoes with shining buckles. Men were more particular about their apparel in those days than we are now. They had great stateliness of behavior, and admitted of little familiarity.

They had heard John Buttrick’s order to fire, which marked the moment when our country was born. The order was given to British subjects. It was obeyed by American citizens. Among them was old Master [Thaddeus] Blood, who saw a ball strike the water when the British fired their first volley. I heard many of the old men tell their stories of the Battle of Concord, and of the capture of Burgoyne.

I lay down on the grass one summer afternoon, when old Amos Baker of Lincoln, who was in the Lincoln Company on the 19th of April, told me the whole story. He was very indignant at the claim that the Acton men marched first to attack the British because the others hesitated. He said, “It was because they had bagnets [bayonets]. The rest of us hadn’t no bagnets.”

One day a few years later, when I was in college, I walked up from Cambridge to Concord, through Lexington, and had a chat with old Jonathan Harrington by the roadside. He told me he was on the Common when the British Regulars fired upon the Lexington men.

He did not tell me then the story which he told afterward at the great celebration at Concord in 1850. He and Amos Baker were the only survivors who were there that day. He said he was a boy about fifteen years old on April 19, 1775. He was a fifer in the company. He had been up the greater part of the night helping get the stores out of the way of the British, who were expected, and went to bed about three o’clock, very tired and sleepy. His mother came and pounded with her fist on the door of his chamber, and said, “Git up, Jonathan! The Reg’lars are comin’ and somethin’ must be done!” . . .

A very curious and amusing incident is said, and I have no doubt truly, to have happened at this celebration. It shows how carefully the great orator, Edward Everett, looked out for the striking effects in his speech. He turned in the midst of his speech to the seat where Amos Baker and Jonathan Harrington sat, and addressed them. At once they both stood up, and Mr. Everett said, with fine dramatic effect, “Sit, venerable friends. It is for us to stand in your presence.”

After the proceedings were over, old Amos Baker was heard to say to somebody, “What do you suppose Squire Everett meant? He came to us before his speech and told us to stand up when he spoke to us, and when we stood up he told us to sit down.”

In Concord, George F. Hoar became lifelong friends with Henry David Thoreau. They met as

schoolboys at different grades, and George later attended the Thoreau brothers’ Concord Academy for a while. It’s unclear whether he

overlapped with Edmund Quincy Sewall, Jr.

However, in an 1891 letter Hoar wrote that as a boy he attended a lecture in Concord where the speaker exhibited the skull of a British soldier killed in 1775. That could only have been

Walton Felch at the town’s lyceum in the spring of 1840.

After the obligatory years at

Harvard, George F. Hoar went into the

law, establishing his practice in

Worcester. Then he went into politics. He served in the

Massachusetts General Court, then the U.S. Congress after the Civil War, and finally the U.S. Senate from 1877 to 1904.

Back home, Hoar helped found what became the Worcester Polytechnic Institute and served as president of the American Antiquarian Society. He also sat on boards of the Smithsonian Institute and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, so he didn’t have a complete aversion to museums holding human remains.

But Sen. Hoar didn’t like the idea of the Worcester Society of Antiquity holding that skull of a British soldier killed on 19 Apr 1775.

TOMORROW:

A private arrangement.