I’ve now

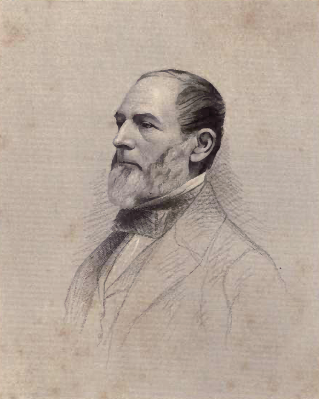

quoted two nineteenth-century accounts from descendants of

Elbridge Gerry,

Azor Orne, and

Jeremiah Lee (shown here) saying that

British soldiers searched the tavern in

Menotomy where they were staying on the night of 18–19 Apr 1775.

The three men, all delegates from

Marblehead to the

Massachusetts Provincial Congress, fled out the back of the tavern and hid outside in the cold.

Less than a month later, Lee died of an illness, which his family attributed to the stress of that night. That obviously made the men’s choices in the early hours of 19 April carry more weight.

There are, however, big problems with the story that part of the British army column searched

Ethan Wetherby’s Black Horse tavern that night.

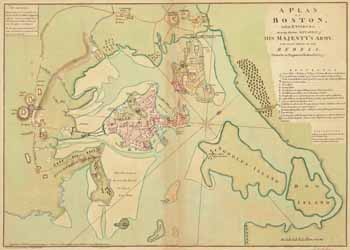

First, Gen.

Thomas Gage’s orders for the march said nothing about looking for committee of safety members along the way. His

intelligence files have no information on the whereabouts of those committee men. Rather, the general wanted his troops to get to

Concord as quickly as possible.

Furthermore, none of the British army officers who wrote reports on that march described searching a tavern in west Cambridge, or anywhere else on their way out.

Finally, no contemporaneous accounts from the provincial side—neither depositions, letters, nor newspaper articles—complained about this search, either. And people made a

lot of complaints in the wake of the Battle of

Lexington and Concord.

There might be a seed of truth at the start of the story. Both versions say a small number of soldiers approached the tavern after the vanguard passed by. It’s conceivable that some redcoats turned aside to use the tavern’s well or outhouse before catching up with the column. But the lore goes much further than that, saying soldiers spent “more than an hour” searching every room in the building, “even the beds.”

The lore offers no corroborating evidence for that detail, such as the landlord’s testimony. In fact, the nineteenth-century versions specify that the committee men

couldn’t point to anything missing as a sign that the soldiers had visited their room:

-

“a valuable watch of Mr. Gerry’s, which was under his pillow, was not disturbed.”

-

“Mr. Gerry’s watch was under his pillow, but it was not disturbed, nor was any of their property taken.”

Ordinarily if everything in a room looks the same as before, we treat that as a sign it

wasn’t searched.

By 1916, Thomas Amory Lee might have spotted that weakness in the traditional tale because his article “Colonel Jeremiah Lee: Patriot” for the

Essex Institute Historical Collections stated: “Gerry’s silver watch and French great coat disappeared.” That’s a direct contradiction of earlier Gerry family lore, and even that new version said Orne’s watch went untouched.

Given the totality of evidence, I think the Marblehead delegates were more worried about arrest than Gerry’s exchange of notes with

John Hancock let on. Seeing hundreds of British soldiers outside their inn, perhaps seeing some of those soldiers coming closer to the building, they bolted for an exit.

There are reports Gerry and perhaps Lee sustained injuries in their flight. Then they stayed outside in the cold until it felt safe to return. Waiting for the whole army column to pass by and go out of sight may have

felt like an hour, but it probably took less time than that.

Finally the three men came back inside, grateful to have escaped arrest. Then came news of the shooting at Lexington, the redcoat reinforcement column, the outbreak of war. The delegates fled the tavern again, this time with their possessions. Lee fell ill soon after, and died on 10 May.

Looking back on the episode decades later, Gerry and Orne—and perhaps even more so their and Lee’s descendants—would have resisted the thought that those sacrifices weren’t really necessary. That the three Marblehead men could have stayed in their warm bedroom, watched the glittering troops march by, and never faced arrest. That Lee might have lived longer.

So they convinced themselves that running outside had been necessary. Not just prudent but necessary. Which meant believing that soldiers came into the tavern and searched the bedrooms, leaving no sign of their presence.