“Ye. uncommon size & penetration of his genius”

The Lockes owned a “large convenient Dwelling-House” situated “near the Northerly side of the Common on the road to Holliston” and “opposite the Meeting-House.”

The attached estate included “two Barnes, and other Out-Houses,” and ninety-two acres of land, including “Pasturage, Arable land, Meadow, &c with a large quantity of good Fruit Trees; as also a valuable Lot of Wood.”

There had been some hurt feelings when Locke had left Sherborn’s pulpit in 1769, but the congregation found a replacement within a year, with the college providing some settlement money. The townspeople didn’t seem to hold a grudge against Locke personally.

In fact, Locke’s neighbors continued to refer to him with the honorifics “Reverend” and “Doctor.” In March 1774 they voted to put him on the committee of correspondence, which after the war started became the committee of public safety.

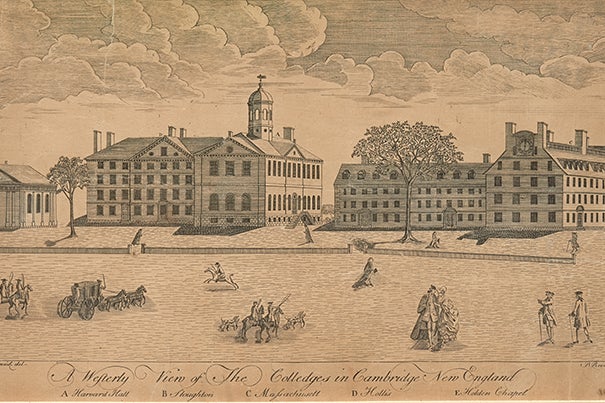

To supplement his income, Locke prepared boys for Harvard, having them board at his house. One student, John Welles, recalled him as “the most learned man in America,” and “a perfect gentleman, dignified.”

The Continental Journal for 22 Jan 1778 reported: “Thursday morning last [i.e., 15 January] died suddenly of an apoplectic fit, the Rev. Dr. Samuel Lock of Sherburn.” According to John Goodwin Locke’s Book of the Lockes, “He died from the bursting of a blood-vessel, when aiding in driving some cattle from his field.” (Sherborn’s published town records say the date was 15 Jan 1777, but apparently someone forgot to start writing the new year. That error confused later people, like the person who carved the headstone shown above.)

Contemporaries glossed over Locke’s adultery. A neighbor wrote: “Some domestic troubles embittered the last years of his life, but he was never known to make a complaint, but bore them with Christian resignation.” His successor at Harvard, the Rev. Dr. Samuel Langdon, is credited with this eulogy:

In Memory of ye. Revd. Samuel Locke D. D. [sic]For the president of a college Locke had embarrassed by having an affair to say he was in “conjugal & parental relations kind, & officious” suggests that some contemporaries shared John Andrews’s opinion that his wife had somehow driven him into the arms of his housekeeper. But Mary Locke left no account herself, and no one else commented on her.

As a Divine he was learned and judicious—In ye. pastoral relation vigilant and faithfull—as a christian devout & charitable—In his friendships firm & sincere—humane affable & benevolent in his disposition—in ye. conjugal & parental relations kind, & officious—ye. uncommon size & penetration of his genius—ye. extensiveness of his erudition—yt. fund of useful knowledge wh. he had acquired—ye. firmness & mildness of his temper & manners—his easiness of access & patient attention to others-join’d with his singular talents for government, procur’d him universal esteem, especially of ye. governers & students of Harvard College over wh. he PRESIDED four years with much reputation to himself & advantage to ye. public—after wh. he retired to ye. private walks of Life, entertaining & improving ye. more confined circle of his friends until his Death wh. was very sudden on ye. 15th: day of January 1778—aged 45.

Be that as it may, Locke left an estate worth over £3,600. The widow Locke continued to live in Sherborn and to raise their three children. There’s an advertisement for settling her estate in the 11 June 1789 Independent Chronicle.

Of Mary and Samuel Locke’s children, Samuel, Jr., became the local doctor. He married Hannah Cowden, and they had four daughters, one dying in infancy. He died in 1788, aged twenty-seven, thus probably before his mother.

In 1792 the Locke family farm was put up for sale. The sellers were the couple’s daughter Mary, the doctor’s widow Hannah, and Samuel Sanger, the same man who had administered the widow’s estate. It evidently did not sell because in 1794 the widow Hannah Locke advertised it again, now on her own.

Mary Locke the daughter died in 1796, aged thirty-three. The family historian wrote: “She had been an invalid for some years before she died.” He also stated: “She was a lady of considerable personal and mental attractions, and if we may judge from the wardrobe which she left, not inattentive to that personal adornment to which many of her sex are addicted.” That judgment seems to be based entirely on the number of gowns in her probate inventory.

The youngest sibling, John Locke, moved from Sherborn to Union, Maine, and then to “Northampton, where he died, as it is said, by drinking cold water when heated.” That death wasn’t so sudden, however, as to preclude seeking medical attention and writing a will. John Locke was only thirty-four years old, continuing the family tradition of dying young.

The Rev. Dr. Samuel Locke’s grave went unmarked for decades. A sexton found his skeleton in 1788 when he was burying the eldest son. By 1853 the former minister’s remains had been dug up and reinterred in a new town cemetery. At the time his skull was judged to show “those phrenological developments which indicate great mental powers.”

When the younger Mary Locke died in 1796, both the Sherborn town records and the local Moral and Political Telegraphe newspaper described her as the minister’s “only daughter,” making a point. According to Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, however, the child Samuel Locke fathered in 1773 was also a girl, named Rebecca Locke. Clifford K. Shipton wrote that “she became a well-known figure in Boston and Worcester,” but I haven’t unearthed any sign of her.