“An oath, certified by a magistrate to be by them taken”

Earlier this summer, I spent a few days discussing Albert Matthews’s 1915 analysis of two forms of the Solemn League and Covenant, and then laying out how I came to the opposite conclusion about which text came from Boston and which from Worcester.

Part of Matthews’s argument was that one of the texts was “more drastic.” But the main pledge of both texts is:

we will not buy, purchase or consume, or suffer any person, by, for or under us to purchase or consume, in any manner whatever, any goods, wares, or merchandize which shall arrive in America from Great Britain aforesaid, from and after the last day of August next ensuing.In that regard, the two versions were equally strict.

One text had this additional promise:

That from and after the first day of October next ensuing, we will, not by ourselves, or any for, by, or under us, purchase or use any goods, wares, manufactures or merchandize, whensoever or howsoever imported from Great Britain, until the harbour of Boston shall be opened, and our charter rights restored.That left the month of September to buy and use goods from Britain imported before 31 August. But nobody seems to have complained about that clause, or the lack of it.

Instead, the sticking point for some opponents was language that appeared in the other text (language which I believe was added to the Boston draft by Worcester’s committee of correspondence, and then endorsed by Boston and adopted by other towns):

That such persons may not have it in their power to impose upon us by any pretence whatever, we further agree to purchase no article of merchandize from them, or any of them, who shall not have signed this, or a similar covenant, or will not produce an oath, certified by a magistrate to be by them taken to the following purpose: viz.The newspaper letter I quoted yesterday specifically complained about “The multiplication of Oaths.” Bringing sworn oaths into this boycott was a step too far for that writer (even though people who signed any form of the covenant didn’t need to swear separate oaths).I —————— of —————— in the county of —————— do solemnly swear that the goods I have now on hand, and propose for sale, have not, to the best of my knowledge, been imported from Great Britain, into any port of America since the last day of August, one thousand seven hundred and seventy four, and that I will not, contrary to the spirit of an agreement entering into through this province import or purchase of any person so importing any goods as aforesaid, until the port or harbour of Boston, shall be opened, and we are fully restored to the free use of our constitutional and charter rights.

In a devout society like colonial New England, sworn oaths carried more weight than other sorts of public promises. Bringing up an oath therefore made this text stronger, thus more radical than the other.

The letter writer seems to have expected people to break their strict non-importation promises, offering excuses or seeking exceptions as many Boston merchants had done in 1769–70. Having people swear to strictly adhere to this boycott wouldn’t make them any more careful about its terms, that writer suggested—it would simply give them an incentive to “disregard” an oath. The letter concluded:

…Society cannot exist when Oaths shall cease to be religiously observed. When that dreadful Event happens among any People, their Lives, Liberties and Properties cannot be safe.Evidently, society depends on us being able to shade the truth in front of our neighbors without worrying about the hereafter.

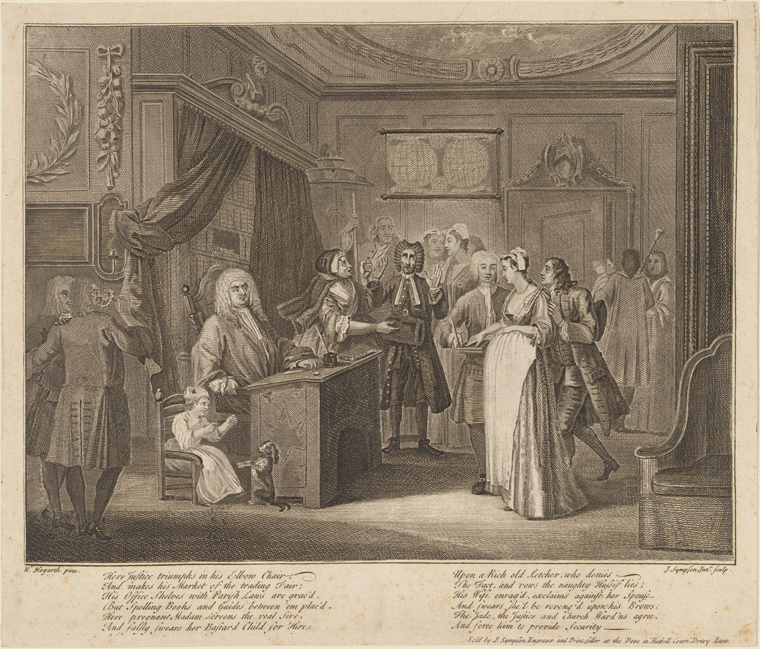

(The engraving above is “Woman Swearing a Child to a grave Citizen” by William Hogarth, courtesy of the New York Public Library.)