Here’s the lineup of upcoming talks at the

David Library of the American Revolution in Pennsylvania. That’s a striking venue with a loyal audience, and its offerings cover the entire war—note how many different people and events proved absolutely crucial to the Revolution.

Thursday, 20 September, 7:30

John Oller, “A Patriot (But Not THE Patriot)”

The author of

The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion Saved the American Revolution will explore the life and military campaigns of

Francis Marion. Like Robin Hood of legend, Marion and his men attacked from secret hideaways before melting back into the forest or swamp, confounding the

British. Although Marion bore little resemblance to the fictionalized portrayals in television and film, his exploits were no less heroic. He and his band of

militia freedom fighters kept hope alive for the patriot cause in one of its darkest hours, and helped win the Revolution.

Thursday, 4 October, 7:30

Bob Drury, “The Existential Moment: How The Valley Forge Winter Saved the Revolution, Created the United States, and Changed the World”

Bob Drury is co-author (with Tom Clavin) of the new book

Valley Forge. In his talk, he will outline how

George Washington and his closest advisers spent six months on a barren plateau 23 miles from enemy-held Philadelphia fighting a war on two fronts—militarily against the British, and politically against a Continental faction attempting to depose him as Commander in Chief of the

Continental Army. How he deftly prevailed on both of these fronts shaped the world as we know it today.

Sunday, 7 October, 3:00

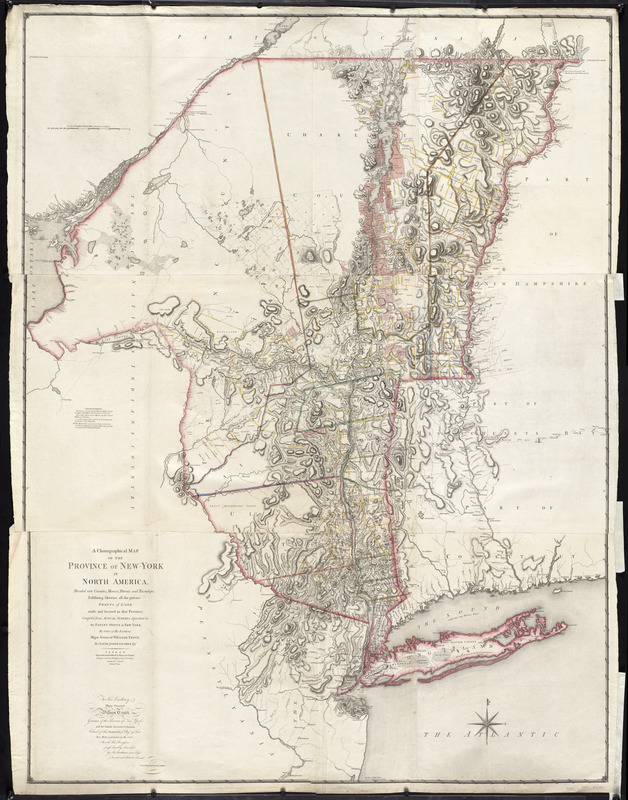

Robert Selig, “The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail in the State of Pennsylvania”

In 2008, President Obama signed legislation establishing the land and water routes that were traveled by the allied

French and American armies to and from

Yorktown in the summer of 1781 as a National Historic Trail. That trail stretches from Newport,

Rhode Island, and Newburgh,

New York, and includes Pennsylvania from Trenton south to Marcus Hook. Yet the very existence of this trail is still largely unknown. Robert Selig, Ph.D., serves as project historian to the National Park Service for the

Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail Project. His lecture will introduce the trail and its historic significance, showing contemporary and modern

maps, and important sites he has identified in his research, some of which was conducted at the David Library!

Wednesday, 17 October, 7:30

An Evening with Nathaniel Philbrick

This program comes in cooperation with nearby Washington Crossing Historic Park, which will host the event. The

New York Times best-selling author, hailed by the

Wall Street Journal as “one of America’s foremost practitioners of narrative nonfiction,” will give a talk about his newest book,

In the Hurricane’s Eye: The Genius of George Washington and the Victory at Yorktown. Tickets are $50 for a single seat, and $80 for two. Each individual or couple admission price includes an autographed copy of

In the Hurricane’s Eye. Proceeds benefit the David Library and the Friends of Washington Crossing Historic Park. Visit

this site to buy tickets in advance.

Thursday, 25 October, 7:30

Stephen Fried, “Reclaiming Dr. Benjamin Rush, Our ‘Lost’ Founding Father”

Bestselling author Stephen Fried, whose latest book is

Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father, will help us see the American Revolution, the Federal Period and the human saga of the entire birth of our nation from the unique, fascinating perspective of founding father, physician, philosopher and confidant

Benjamin Rush.

Thursday, 1 November, 7:30

Ricardo A. Herrera, “American Citizens, American Soldiers: Civic Identity and Military Service from the War of Independence to the Civil War”

From 1775 through 1861, American soldiers defined and demonstrated their beliefs about the nature of the American republic and how they, as citizens and soldiers, were part of the republican experiment. Despite uniquely martial customs, organizations, and behaviors, the United States Army, the states’ militias, and the war-time volunteers were the products of their parent society. Understanding American soldiers of all ranks, in war and in peace, helps us understand more about American society writ large and how that society shaped its armed forces in the years of the Early Republic. A former David Library Fellow, and currently Professor of Military History at the School of Advanced Military Studies in Kansas, Ricardo A. Herrera, Ph.D., is the author of

For Liberty and the Republic: The American Citizen as Soldier, 1775-1861.

Thursday, 8 November, 7:30

Christopher S. Wren, “Vermont: The Most Rebellious Race”

Before

Vermont was Vermont, it was a British territory fought over by such figures as

Ethan Allen, who helped form the American Revolutionary War militia known as the Green Mountain Boys. This lecture, by the author of

Those Turbulent Sons of Freedom: Ethan Allen's Green Mountain Boys and the American Revolution, will consider the story of the tough, brave, and wild crew of characters who faced some of the harshest combat in the American Revolution, and made their own rules to create an independent Vermont.

Sunday, 18 November, 3:00

Tilar J. Mazzeo, “The Private Lives and Loves of the Schuyler Sisters”

Mazzeo is the author of the new biography

Eliza Hamilton: The Extraordinary Life and Times of the Wife of Alexander Hamilton. Her lecture will take a lively look into the lives of

Eliza,

Angelica and Peggy, the daughters of

Philip Schuyler, and the context of colonial and early national

women’s lives in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The lecture will draw on information from private family letters and documents, and will cover everything from Eliza Hamilton’s first crushes to the Schuyler family wedding

cake recipe to how colonial women leveraged coterie networks to support

spy rings in the Revolution.

Thursday, 6 December, 7:30

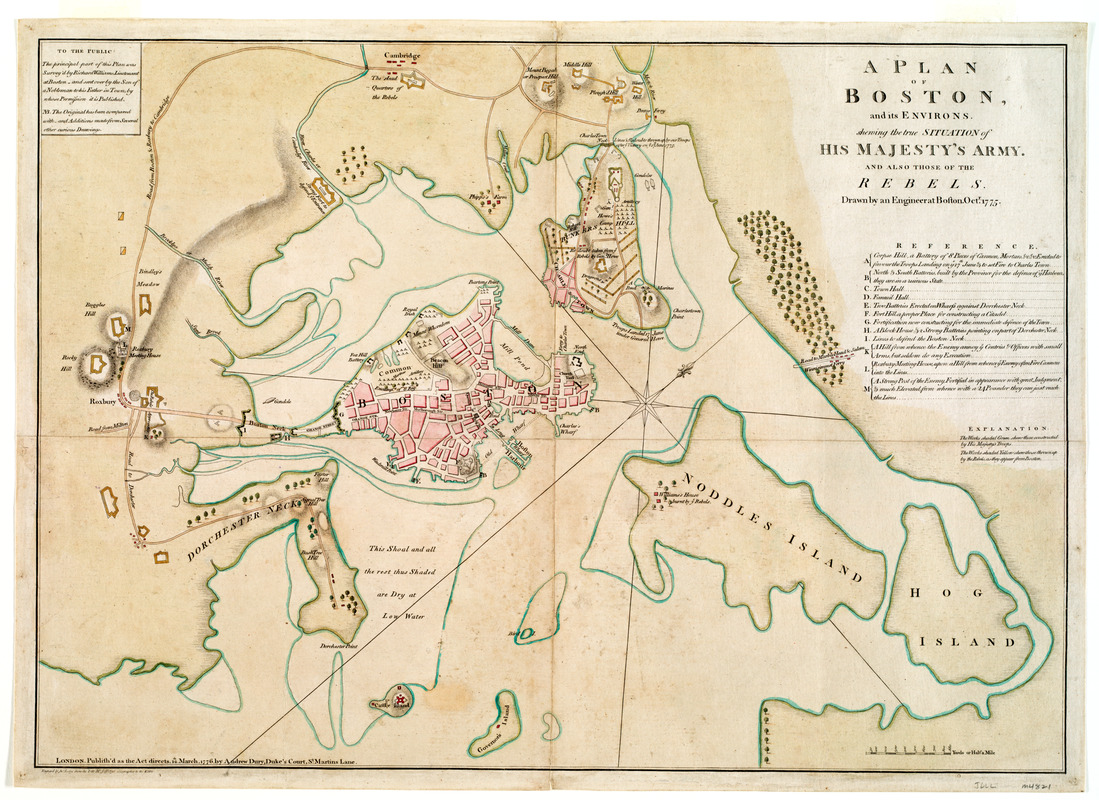

Christian di Spigna, “‘The Greatest Incendiary in all America’: The Rise and Fall of Dr. Joseph Warren”

Joseph Warren was the Boston physician who played a prominent role in the earliest days of the Revolution. As president of the revolutionary

Massachusetts Provincial Congress, it was he who enlisted

Paul Revere and

William Dawes on April 18, 1775, to leave Boston and spread the alarm that the British garrison in Boston was setting out to raid the town of

Concord. Christian di Spigna is the author of

Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution's Lost Hero. His lecture will trace Warren’s rise from humble beginnings to his bloody death at

Bunker Hill, and examine Warren’s postmortem journey over the years from Revolutionary hero to relative obscurity.

(My own talk at the David Library a couple of years back can be

viewed here.)