A Boston Boy Rebuilding the British Empire

Yesterday’s précis of the life of Charlotte Biggs promised a connection to pre-Revolutionary Boston.

You remember that young man whom Charlotte fell in love with as a teenager before her marriage? The one who went off to India to make his fortune?

His name was David Ochterlony, and he came from Boston.

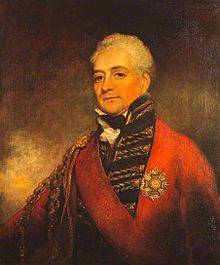

Ochterlony (shown here) was born on 12 Feb 1758, eldest son of a Scottish merchant captain with the same name. His mother was Katherine Tyler, a niece of the first Sir William Pepperrell. The family house from 1762 was a brick mansion on Back Street.

In 1766 David entered John Lovell’s South Latin School. The year before, however, his father had died on a voyage to the Caribbean. The estate was in debt, not paid off until well after the war.

What happened next to young David and his siblings isn’t easy to sort out. There’s evidence he spent some time studying under Samuel Moody at the Byfield school endowed by Lt. Gov. William Dummer, now the Governor’s Academy.

Katherine Ochterlony moved to Britain and in the early 1770s married Sir Isaac Heard, a Royal Navy veteran, merchant, and, of all things, heraldric official.

The Ochterlony children joined their mother in Britain, and Heard welcomed them into his family. It’s said that David developed a close relationship with his stepfather.

When the American War began, David Ochterlony showed his loyalty to the British Empire by joining the army, or pledging to. During this time in London, the teenager evidently met Charlotte Williams, and she fell in love with him.

Ochterlony shipped out to India as an army cadet. In 1778 he gained the rank of ensign, and in three years became quartermaster for the 71st Regiment. During the Second Anglo-Mysore War, connected with Britain and France’s fight on the other side of the world, Ochterlony was captured and spent two years as a prisoner. Then he returned to army staff positions.

The loss of the most populous North American colonies turned British attention to India, and Ochterlony’s career rose with the empire there. In 1812 he became a major general, and in 1816 a baronet and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. (Those are the sorts of honors his stepfather loved studying.) In the first quarter of the nineteenth century Ochterlony was among the British Empire’s most powerful administrators on the subcontinent.

Gen. Sir David Ochterlony was known for adopting the local aristocratic lifestyle rather than maintaining British, or Boston, ways. He had thirteen concubines or wives, who reportedly paraded around Delhi on elephants. A son by one of those women became the heir to his baronetcy after the general died in India in 1825.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, the teen-aged girl who had become Charlotte Biggs, author and intelligence source, was still carrying a torch for the aspiring officer she had met in the 1770s. When she wrote an autobiography late in life, she addressed it to Ochterlony, evidently still hoping to see him again. (That manuscript became the basis of Joanne Major and Sarah Murden’s biography, A Georgian Heroine.)

You remember that young man whom Charlotte fell in love with as a teenager before her marriage? The one who went off to India to make his fortune?

His name was David Ochterlony, and he came from Boston.

Ochterlony (shown here) was born on 12 Feb 1758, eldest son of a Scottish merchant captain with the same name. His mother was Katherine Tyler, a niece of the first Sir William Pepperrell. The family house from 1762 was a brick mansion on Back Street.

In 1766 David entered John Lovell’s South Latin School. The year before, however, his father had died on a voyage to the Caribbean. The estate was in debt, not paid off until well after the war.

What happened next to young David and his siblings isn’t easy to sort out. There’s evidence he spent some time studying under Samuel Moody at the Byfield school endowed by Lt. Gov. William Dummer, now the Governor’s Academy.

Katherine Ochterlony moved to Britain and in the early 1770s married Sir Isaac Heard, a Royal Navy veteran, merchant, and, of all things, heraldric official.

The Ochterlony children joined their mother in Britain, and Heard welcomed them into his family. It’s said that David developed a close relationship with his stepfather.

When the American War began, David Ochterlony showed his loyalty to the British Empire by joining the army, or pledging to. During this time in London, the teenager evidently met Charlotte Williams, and she fell in love with him.

Ochterlony shipped out to India as an army cadet. In 1778 he gained the rank of ensign, and in three years became quartermaster for the 71st Regiment. During the Second Anglo-Mysore War, connected with Britain and France’s fight on the other side of the world, Ochterlony was captured and spent two years as a prisoner. Then he returned to army staff positions.

The loss of the most populous North American colonies turned British attention to India, and Ochterlony’s career rose with the empire there. In 1812 he became a major general, and in 1816 a baronet and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath. (Those are the sorts of honors his stepfather loved studying.) In the first quarter of the nineteenth century Ochterlony was among the British Empire’s most powerful administrators on the subcontinent.

Gen. Sir David Ochterlony was known for adopting the local aristocratic lifestyle rather than maintaining British, or Boston, ways. He had thirteen concubines or wives, who reportedly paraded around Delhi on elephants. A son by one of those women became the heir to his baronetcy after the general died in India in 1825.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, the teen-aged girl who had become Charlotte Biggs, author and intelligence source, was still carrying a torch for the aspiring officer she had met in the 1770s. When she wrote an autobiography late in life, she addressed it to Ochterlony, evidently still hoping to see him again. (That manuscript became the basis of Joanne Major and Sarah Murden’s biography, A Georgian Heroine.)