Revisiting the Spies of 1775

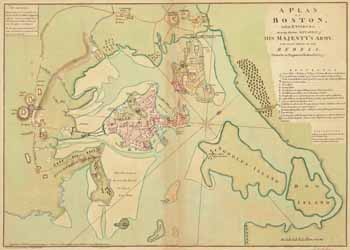

My topic was “The Spies of 1775,” reeling off stories of disparate people drawn into intelligence-gathering efforts on both sides of the siege lines around Boston.

Since I didn’t want to go back over the spies at the center of The Road to Concord, I talked about:

- Henry Knox

- William Jasper

- Dr. Benjamin Church, Jr.

- Benjamin Thompson

- Julien-Alexandre Achard de Bonvouloir et Loyauté

- Rev. John Carnes

- Thomas Machin

- Mary Wenwood

- John Skey Eustace

Speaking to a capacity audience in the Francis Falkner Hearing Room on March 31, author and historian John L. Bell related a fascinating story of the spies used by the commanders on both sides of the conflict. While many informants chose to provide information due to loyalty to their cause, others were primarily driven by money, property, revenge, or self-promotion.Acton 250 television has now posted its video recording of the event, neatly edited to remove evidence of some technical difficulties.

And here’s a postscript to that evening. On Friday I participated in the conference “1775: A Society on the Brink of War and Revolution” hosted by the Concord Museum and organized by the David Center for the American Revolution at the American Philosophical Society and and the Massachusetts Historical Society.

That program included Iris de Rode from the University of Virginia presenting on “French Observers of Early American Unrest: How Lexington and Concord Shaped France’s Entry into the American Revolution.” Among other people she discussed Bonvouloir, one of the spies I’d described in Acton, so I gossiped with her afterwards.

Bonvouloir and his companion, the Chevalier d’Amboise, were in London in the late summer of 1775. A British government agent pumped them for information. The Frenchmen described witnessing “the Affair of Lexington, and the Affair of the 17th [Bunker Hill].” They claimed to have met “Putnam and Ward.”

But Dr. de Rode said that there’s no evidence of similar reports in French government sources. Even though Bonvouloir lobbied to become his government’s agent to the American rebels, which would make his experience with the war relevant, he doesn’t appear to have told those stories to the French ambassador to pass on to the Foreign Ministry. So she thinks he was just talking through his no doubt fashionable hat.

The British intelligence service was definitely shadowing Bonvouloir in London, and he was definitely involved in a secret mission to Philadelphia at the end of 1775. So he fits into a talk on spies. But whether he was in New England in 1775 is in question. I must consider the possibility that in London he engaged in a disinformation campaign—not to help the Americans or the French but to make himself look more important.

.jpeg)