After the royal authorities published the private letters they had captured on

Benjamin Hichborn in August 1775, what was the fallout for the men who had written those letters?

Unfortunately for unabashed gossips, there aren’t a lot of good sources on

Benjamin Harrison’s reaction. We can imagine that he quickly wrote another letter to Gen.

George Washington promising that his earlier one had never really hinted that they might both enjoy a pretty washerwoman’s daughter. (If so, that follow-up letter doesn’t survive.)

It’s conceivable that Harrison volunteered to be part of the

Continental Congress committee that met with Washington in

Cambridge in October in order to confirm their personal relationship.

In November, Harrison was

very insistent on having a ball in Philadelphia to honor

Martha Washington, passing through the city on her way north. Was he so passionate because he wanted to make up for embarrassing her? That’s possible, but it’s also possible that Harrison had laughed off the publication of the falsified letter and just liked parties.

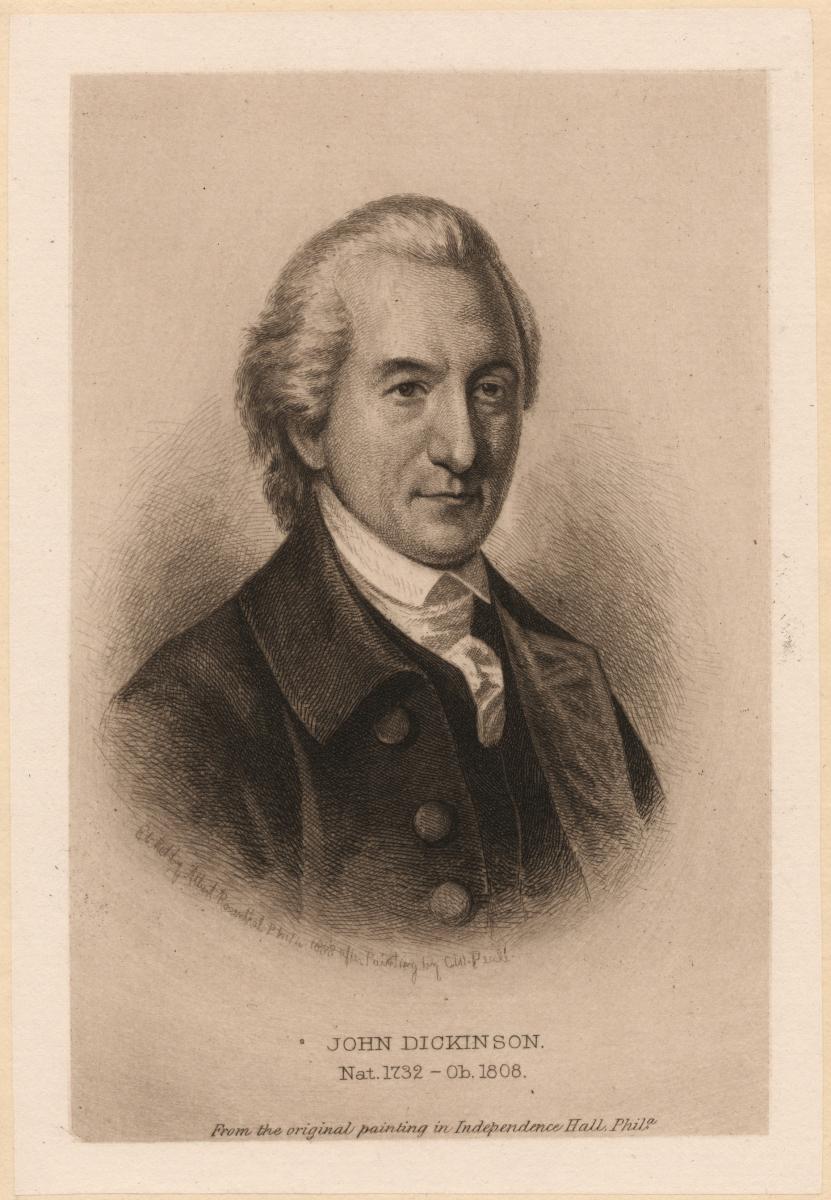

As for

John Adams, the letters published over his initials had managed to denigrate most of the Congress in general,

John Dickinson (shown above) in particular, and Gen.

Charles Lee in passing.

Printers in Philadelphia chose not to reprint the letters from the

Boston News-Letter, but things were still pretty bad for a while. On 16 September Adams wrote in his diary:

Walking to the Statehouse this Morning, I met Mr. Dickinson, on Foot in Chesnut Street. We met, and passed near enough to touch Elbows. He passed without moving his Hat, or Head or Hand. I bowed and pulled off my Hat. He passed hautily by. The Cause of his Offence, is the Letter no doubt which Gage has printed in Drapers Paper.

And Dickinson wasn’t the only one snubbing Adams, according to the memoir of his friend

Dr. Benjamin Rush:

It exposed him to the execrations of all the prudent and moderate people in America, insomuch that he was treated with neglect by many of his old friends. I saw this profound and enlightened patriot…walk our streets alone after the publication of his intercepted letter in our newspapers in 1775 an object of nearly universal detestation.

A British

spy in Philadelphia named

Gilbert Barkly reported that local

Quakers had decided that Adams was dangerous to America; he also planned to push that sentiment along by circulating his own copies of the letters.

Adams might have told people he hadn’t written exactly what was published. In his autobiography decades later he said: “Irritated with the Unpoliteness of Mr. Dickinson and more mortified with his Success in Congress, I wrote something like what has been published. But not exactly. The British Printers made it worse, than it was in the Original.” And the originals are gone, so there’s no proof one way or the other.

But historians generally think that the

Boston News-Letter quoted Adams accurately. Unlike the Harrison letter, there are no copies

without the embarrassing lines. Adams never identified what bits he hadn’t written, but instead tried to justify one of the more controversial parts (

as I quoted yesterday). Most tellingly, Adams had written quite similar things in previous letters, including two he’d sent the previous day.

Looking back, Adams claimed that the publication of his letters had actually

benefited him, and he may have been right. For one thing, he liked to think of himself as unpopular because of his principled stands. At times he exaggerated the criticism and downplayed the support he received to justify that feeling. But in the summer of 1775, he could feel that way naturally.

Furthermore, the publication of the letters opened a public discussion on the possibility of independence, and raised his profile as an advocate for it. In his autobiography Adams even wrote that

Joseph Reed had told him, “Providence seemed to have thrown these Letters before the Public for our good.”

Meanwhile, events were bending Adams’s way. Before copies of his letters arrived in London, the royal government had already declared all the colonies at the Congress to be in rebellion and rejected the

Olive Branch petition. Thus, by the end of the year Dickinson’s moderate position had lost some credit and Adams’s advocacy of independent governments seemed smart.

In fact, on 1 Jan 1776, while Adams was back home in Massachusetts, the

Boston Gazette reprinted the letters. Obviously, printer

Benjamin Edes, working out of his temporary quarters in

Watertown, didn’t view those documents as too awkward or scandalous to share with the world.

But there was still that comment about the “Oddity” of Gen. Lee.

TOMORROW: Abigail Adams extends the hand of friendship.