“The infamous Capt. Beeman”

Three of those people were well known Patriot leaders: Dr. Joseph Warren, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock.

The fourth was a Loyalist scout for the British troops identified as “the infamous Capt. Beeman.” Is there any more evidence about such a figure, especially evidence not publicized by October 1775? If so, that would suggest that Belknap truly heard some inside information.

And indeed we can identify “Capt. Beeman.” That must be Thomas Beaman (1729–1780), a Loyalist refugee from Petersham, Massachusetts.

Beaman was born in Lancaster. He joined Gov. William Shirley’s 1755 expedition against Acadia as a sergeant under Capt. Abijah Willard, and before the end of that war he was a captain under Col. Willard at the capture of Montréal. From then on people called him “Captain Beaman” even in peacetime.

In the 1760s Beaman was married and settled in Petersham. The first and so far only minister of that town was the Rev. Aaron Whitney (1714–1779). Unlike most of his Congregationalist colleagues in New England, Whitney strongly supported the royal government in the political disputes of the 1760s and 1770s.

So did Beaman. There was an argument and lawsuit over a schoolhouse around 1770 that I’ll save for later. Instead, let’s skip ahead to late 1774 after royal authority outside Boston broke down. According to Petersham town records, Beaman was among fourteen local men who banded together and agreed:

That we will not acknowledge or submit to the pretended Authority of any Congresses, Committees of Correspondence or other unconstitutional Assemblies of Men, but will at the Risque of our Lives, and if need be, oppose the forceable Exercise of all such Authority.A 2 January Petersham town meeting summoned those men by name to explain themselves or repent. Only two showed up, defiantly maintaining their position. The meeting then determined:

Therefore as it appears that those persons still remain the incorrigable enemies of America and have a disposition to fling their influences into the scale against us in order to enslave their brethren and posterity forever, and after all the friendly expostulations and entreaties which we have been able to make use of, we are with great reluctance constrained to pronounce those, some of which have heretofore been our agreeable neighbors, traitorous paricides to the cause of freedom in general and the United Provinces of North America in particular…The meeting urged townspeople not to have any commercial dealings with those men, even planning to print up 300 handbills at town expense. The Boston newspapers reported on that resolution.

Customs Commissioner Henry Hulton left this version of what happened next, starting in February 1775:

A number of Inhabitants in the town of Petersham, who had entered into an association for their mutual defence, finding the spirit of persecution very strong against them, assembled together in an house, resolving to defend themselves to the utmost.Petersham’s local historian says that siege concluded on 2 March.

The house was soon surrounded by many hundreds of the people, and they were obliged after some days to capitulate and submit. The people, after disarming them, ordered them to remain each at his own house, not to depart from thence, or any two of them to be seen together upon pain of death.

Beaman then probably moved his family into Boston, as many other prominent Loyalists did. [ADDENDUM: Further research cited in the comments below shows that Beaman’s wife and children remained in Petersham until early 1779, when the Massachusetts legislature permitted them to travel through Newport to join him in New York City.] But according to the account his heirs later gave the Loyalists Commission, paraphrased in E. Alfred Jones’s The Loyalists of Massachusetts, “he, at the request of General Gage, frequently traveled the country to discover the real designs of the leaders of the rebellion.”

The Beaman family’s claim also stated that “he was a volunteer (as a guide to Lord Percy) with the military detachment to Concord.” Percy got only as far as Lexington, however. According to Belknap’s informant, Beaman was actually a scout for the first British column under Lt. Col. Francis Smith; those soldiers “landed on Phips’s Farm, where they were met by the infamous Capt. Beeman, and conducted to Concord.”

Furthermore, the New-England Chronicle newspaper of 12 Sept 1776 referred to “Capt Beeman, of Petersham (who piloted the ministerial butchers to Lexington).” And Lemuel Shattuck’s 1835 history of Concord, published before many Loyalist sources became available, stated: “It is also intimated that tories were active in guiding the regulars. Captain Beeman of Petersham was one.” Those sources suggest that locals recognized Beaman among the redcoats, as Belknap’s information implies.

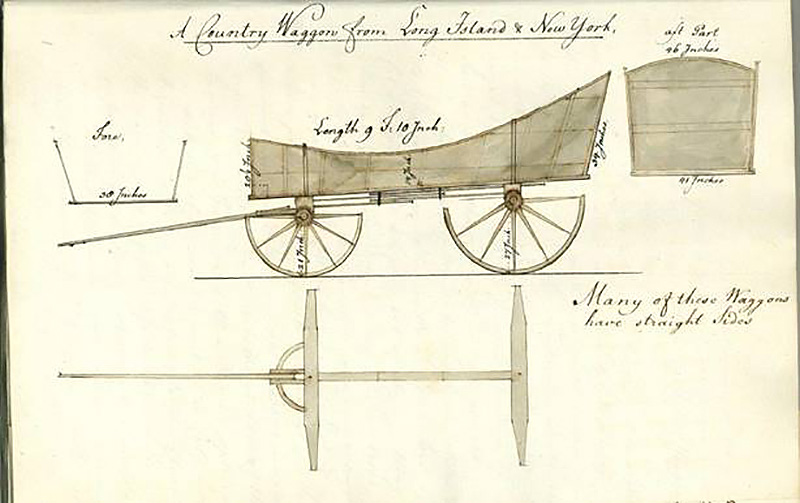

Back in Boston, Gen. Gage rewarded Thomas Beaman in May by appointing him wagon-master to the army. Later in 1775 Beaman became a first lieutenant in the Loyal American Association, a militia company led by his old commander Abijah Willard, which never saw combat.

Beaman kept the position of wagon-master under Gen. William Howe. He traveled with the king's army, working in and around British-occupied New York until he died in November 1780. By then the state of Massachusetts had banished him and confiscated his property. Beaman's widow and children settled in Digby, Nova Scotia.

We thus have our first indication that Belknap’s October 1775 account of the march to Concord came from someone who had at least some reliable, little-known information.