“You shake it within an Inch of my Nose”

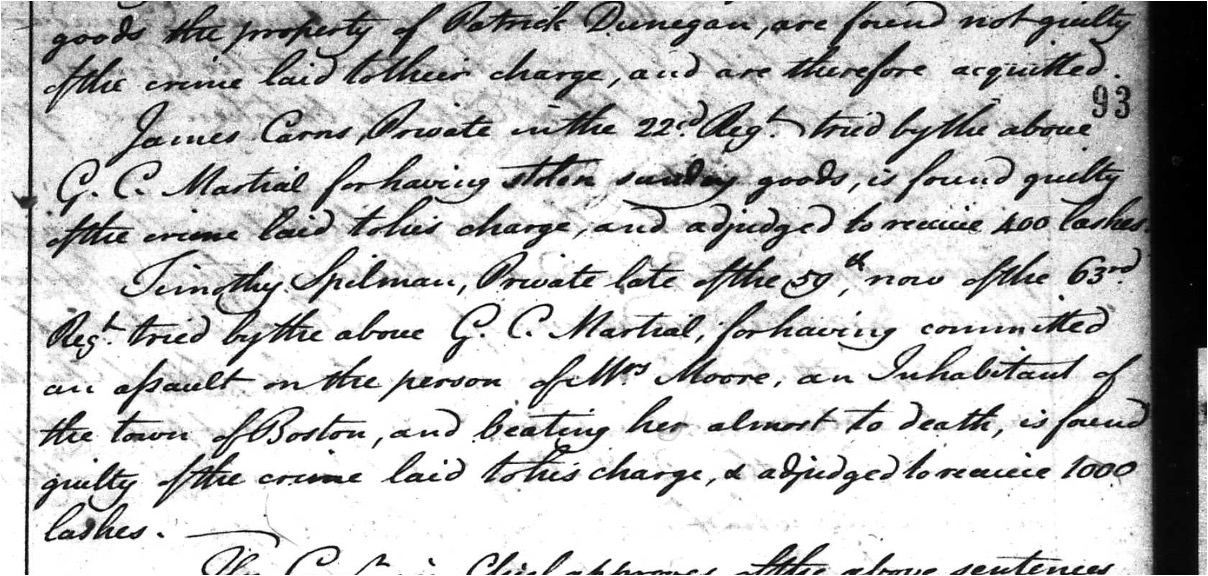

I’m therefore retelling that story in more detail using the court documents published by the Rhode Island Historical Society in 2006 (available as a P.D.F. from Family Search) and other sources.

In 1761 Potter was a wealthy gentleman in Bristol, Rhode Island. He’d been born in that town forty-one years earlier to a poor or middling family. He’d therefore grown up without much schooling, trained to be a cooper. But because of a privateering windfall at the start of King George’s War, Potter had made himself into one of the richest men in the whole colony.

Reflecting his new genteel status, Capt. Potter took on prestigious positions in politics and the church. He became a warden of the local Anglican church, St. Michael’s. Few New England towns of Bristol’s size—about 1,200 people in 1774—had an Anglican church, but this was at the coast and therefore served mariners.

The minister of St. Michael’s was the Rev. John Usher. He was the son of a wealthy bookseller who had risen to be lieutenant governor of New Hampshire. After graduating from Harvard College, Usher had joined the Church of England, defying the New England orthodoxy. The missionary Society for the Propagation of the Gospel paid part of his salary, and his congregants sometimes paid the rest.

In 1761 Usher was over sixty years old. His exact age is unclear since his tombstone says he was seventy-five when he died in 1775, but a memorial plaque later installed in his church says he was eighty. Either way, he’d been the minister at St. Michael’s since 1724, when Simeon Potter was still a little boy.

According to Usher’s report back to the S.P.G., the trouble started because

Notwithstanding he [Potter] has an agreeable wife, he has by report for some years back kept a criminal conversation with a young woman, one of my parish. . . . After many general hints from the Pulpit…I told her what reason I had to suggest she was guilty of the notorious sin of Adultery. . . . Upon this she told the man immediately what I had saidFrankly the minister shouldn’t have been surprised by that.

On the morning of 14 August, Charles Munro said, “the Rev. Mr. John Usher and Capt. Simeon Potter…engaged in warm words or Differing” on the street. Richard Smith added that Usher told Potter, “wherever he went there was whoring carried on.” Smith also quoted the men as saying:

[Potter:] if it wont for your Age and Gown I would not have your Cane shook over my headSimeon Potter, despite his fearsome reputation, was “small in stature,” according to Father Elzear Fauque. Also, in the manners of the time clubbing another man with a cane implied that the caner was a gentleman and the canee was not; given Potter’s background, his class status might have been a sensitive spot.

[Usher:] I don’t shake it over your head nor mean to shake it over

[Potter:] you shake it within an Inch of my Nose

The minister’s son, Hezekiah Usher, called this “Ill treatment” of his father. Potter may also have said something about the minister’s daughter, but I can’t find another trace of her.

On 18 August, Usher and Potter met yet again on Church Lane. They picked up where they had left off. Hezekiah Usher stated:

I heard my Father say to sd. Potter if ever he cast any more reflections on his Family especially on his daughter twould cause him to reflect on his family and upon that the said Potter came up to my Father who was then on the edge of the Gravell’d Walk and said who of my Family and my Father said Your FatherPotter’s father, Hopestill Potter, was in fact sitting in a chair at his own front door nearby.

The quarrel caught the ears of several neighbors, though trees along the street blocked some people’s views. Witnesses agreed that Usher was holding his walking-stick in the middle, waving it around as he spoke. Some said this was “Usher’s naturall way of Shaking his Cane at any Person when he is earnest in talk.” One said the cane was “up as if he was agoing to strike.” But all the trial witnesses agreed they never saw the minister actually touch the captain.

According to Hezekiah Usher, after his father mentioned the captain’s father, Capt. Potter “rusht close up to my Father and said what reflections can you cast on him”? Usher replied, “I’ll blow him up.”

The captain then punched his sexagenarian minister in the face.

TOMORROW: In court.