“Ought to be paid by the United States”

One came from William Burbeck, who before the war had a job managing munitions in Castle William as well as helping to lead Boston’s militia artillery train.

I quoted Burbeck’s account last month. Because Williams took the risk of helping him get out of town, Burbeck was able to become second-in-command of Massachusetts’s artillery regiment.

As for Williams’s loyalty, Burbeck wrote:

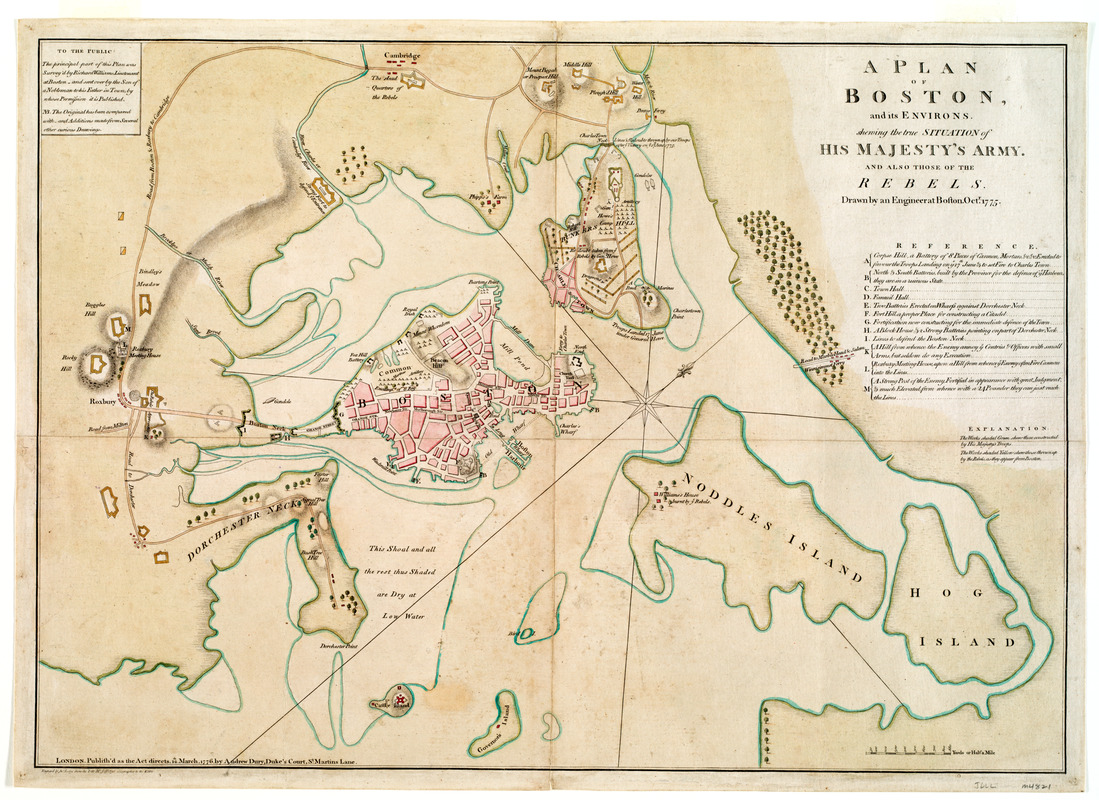

it was Done at ye Risque of Every thing that is Dear And [he] informd. me that he was ready to save me or his Country in any thing that he CouldBurbeck signed that account (it’s not written in his handwriting) on 17 Apr 1776, just after the siege, as the Massachusetts legislature was moving to fortify Noddle’s Island. Obviously that document was meant to answer suspicions about Williams’s loyalty and willingness to provide provisions, even passively, to the British military the previous spring.

I know of but few men if Any in America that would have taken such Risques they being in his then situation (on an Island Surounded by men of war)—

Mr. Williams Complaynd. to me of the Ill treatment he Recd. from the Enemy that his family had been abused And his Interest taken from him & Recd. nothing therefor and that his situation was Dredfull, That he wished his Interest was off the Island and himself in the Country.

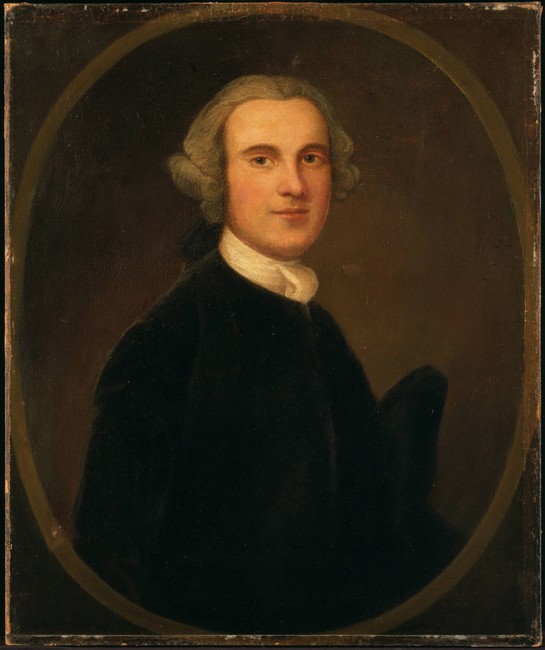

Williams also collected two statements signed by Moses Gill (shown above), prominent Patriot politician from the town of Princeton. One is dated 20 Mar 1786 and written in what looks like the same hand as the Burbeck statement. That document was composed for multiple people to sign, but only Gill did. It said:

in the year 1775 we were appointed by the Government A Committee of Supplies for the Army that when Genrl. [Israel] Putnam Removed the Stocks from Noddles Island, Among which were a Number of Horses which were Committed to our Care, And Upon Genrl. [George] Washington taken the Command of the Army they were with other Stores turnd. over to Colo. [Joseph] Trumbell the Continental Commissary Genrel at CambridgeThe other document signed by Gill isn’t dated, but it responds to an “account above”—probably meaning Williams’s inventory of lost property. As quoted yesterday, that accounting included “43 Elegant Horses...@ 30£.” The statement said:

I cannot with precision recollect the number, yet I believe the above amount is too high charged either with respect to the number or value of the horses.And then the scribe inserted “not” in front of “too high.” I think that was the intended meaning all along, given the rest of the sentence, but that particular edit does raise eyebrows.

Williams also claimed to have lost “3 Cattle” and “220 Sheep.” Gill responded:

As to the Cattle & Sheep charged above, I have no personal knowledge in what manner they were applied, but I have no doubt they were used for the benefit of the American Army. as I was informed so by officers & others at that timeThe bottom line for Gill:

Upon the whole, the account above charged is in my opinion just & ought to be paid by the United States.Williams was already in discussions with a representative of the national government.

TOMORROW: A federal agent.