“With Geat diffickalty We Exaped With our Lives”

The royal governor moved back to Boston in the last week of that month after an unsuccessful confrontation with the local committee of safety.

Richardson and Wilmot went to the Stoneham home of Kezia and Daniel Bryant, Richardson’s sister and brother-in-law, as I recounted yesterday. They were there on 3 September.

When I first wrote about Wilmot’s story for what was then New England Ancestors magazine, I didn’t realize the significance of that date. That was the day after the “Powder Alarm.”

That event showed how powerless Gov. Gage was outside of Boston. Up to five thousand militiamen had marched into Cambridge, demanded that royal appointees resign, chased Customs Commissioner Benjamin Hallowell for miles, and surrounded Lt. Gov. Thomas Oliver’s mansion until he signed a resignation. And there was no response from the royal government.

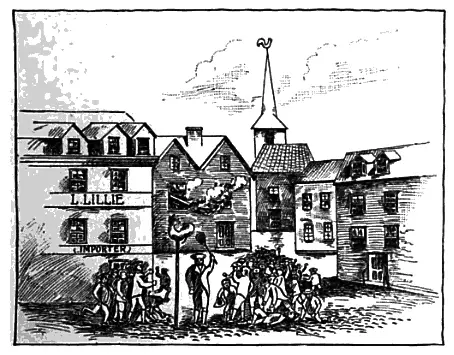

If Gage couldn’t protect high officials in Cambridge, right across the Charles River, he certainly couldn’t protect an infamous child-killer up in Stoneham. And on 3 September, a rural mob came for Richardson.

According to Wilmot’s petition to Secretary of State Dartmouth:

about Eleven a Clock at Night thee came forty men armed with Goons and Suronded the house of Mr. Brayant—and broke his Windows Strocke out on of his Wife Eyes, and swore they would distroy us for we Ware Toary and Enemys to there Countery—and With Geat diffickalty We Exaped With our Lives and Came to Boston under the protection of the fourth Rigment of foot Quartred there.His Majesty’s 4th Regiment of Foot was camped on Boston Common.

Richardson and Wilmot must eventually have gotten on board H.M.S. St. Lawrence as planned. They were in London on 19 January when they signed their petitions to Lord Dartmouth. Judging by the handwriting (and spelling), Wilmot wrote both petitions, and Richardson added his signature.

On January, undersecretary John Pownall sent those papers to his counterpart at the Treasury Office, Grey Cooper. He wrote:

As the inclosed Petitions relate to Services performed and Hardships sustained by the Petitioners as Officers of the Revenue, I am directed by the Lord of Dartmouth to transmit them to you and to desire that you will communicate them to Lord North.In other words, this is a Customs service problem, so it’s up to your department to deal with it.

Treasury officials read the papers on 26 January, and a note on the outside of the bundle states that the two men were paid £10 each.

And with that, “the rank, bloody, and as yet unhanged Ebenezer Richardson” departed from the historical record.