New York Magazine’s Curbed website just

shared an extraordinary article by Reeves Wiedeman titled “The Battle of Fishkill.”

It details the long and ongoing conflict between a

New York restaurateur and property developer named Domenic Broccoli and a group of local preservationists named the

Friends of the Fishkill Supply Depot.

The land in question was part of a

Continental Army logistics site.

Archeologists have found bodies buried there, with ground-penetrating radar turning up signs of more. This has raised the question whether the land should be mostly set aside for study and commemoration, partially preserved, or developed as planned into a retail site called

Continental Commons.

Wiedeman writes:

For more than a decade, the Friends [of the Fishkill Supply Depot] have argued — based on some evidence, but not as much as they would like — that there are more Revolutionary War soldiers buried on [Domenic] Broccoli’s land than anywhere else in the United States.

Broccoli argues that this is rubbish and accuses his foes — with some evidence, but not as much as he would like — of going so far as to plant human remains on his lot in their effort to make it seem more grave-stuffed than it actually is. . . .

The Friends of the Fishkill Supply Depot are a group of history buffs and retiree volunteers, and yet Broccoli claimed he had found it necessary to spend more than a million dollars battling them with archaeologists, lawyers, and the private investigators he hired as “spies” to infiltrate the Friends. As it happened, one of his spies was at the Memorial Day protest holding up a STOP CONTINENTAL COMMONS sign while surreptitiously recording the group in case anything might help the RICO case Broccoli was building.

Broccoli insists that he’s not anti-history. He doesn’t dispute the fact that people are buried on his land or that the area is steeped in Revolutionary significance; his vision for the IHOP [in Continental Commons] involves a wait staff in tricorne hats and bonnets. But it was still a bit of a mystery exactly whose bones were buried on his property and who put them there.

And, besides, if there really were hundreds of soldiers beneath the ground, Broccoli believed it to be self-evident that he was the one pursuing the vision of life, liberty, and happiness that George Washington’s troops had fought and died for: the right to sell pancakes where they were buried.

In that last point, Broccoli’s not wrong. The Founding generation didn’t value landscape preservation. They put up small monuments in a few spots, like the hard-to-farm crest of Breed’s Hill in

Charlestown, but plowed and built over most battlefields and other military sites. That’s why the only

fortifications remaining from the

lines around Boston are the small, late-built earthworks in Washington Park in

Cambridge, preserved solely by the Dana family for generations.

Historical preservation became an American value in the late 1800s. By then, of course, the Revolutionary generation had died out. Fewer sites survived. What remained seemed all the more precious. With industrialization, it became easier to preserve (or restore) battlefields in rural areas, but urban sites got swallowed even faster.

The Fishkill Supply Depot didn’t make the cut for preservation then. The local culture barely remembered it, in fact. It was a logistical site, well away from the fighting. There was no ‘Battle of Fishkill’ to commemorate. Compared to other places (most, but not all, already preserved or commemorated in some way), its significance might fade.

Nonetheless, many Continental soldiers died at the site.

Diseases spread naturally when eighteenth-century people gathered in large numbers. Andrew Wehrman, author of

The Contagion of Liberty, has tweeted that Fishkill was also a site of mass inoculation against

smallpox, which (given the use of the actual live virus at that time) meant a site of many smallpox deaths.

Our contemporary culture is more squeamish about

dead bodies and graveyards than our ancestors were. Many of greater Boston’s hallowed burying-grounds have actually been excavated and relandscaped over time before arriving at what we now perceive to be their historic shape. We’d have a harder time stomaching that process now, even though there are probably fewer Revolutionary remains than ever.

As for the Fishkill Supply Depot, there doesn’t seem to be any resolution in sight. Though Sen. Charles Schumer supports the idea of making some of the land into a new national park, there are lots of details to be worked out and support to line up. This deadlock might end only when more people die out.

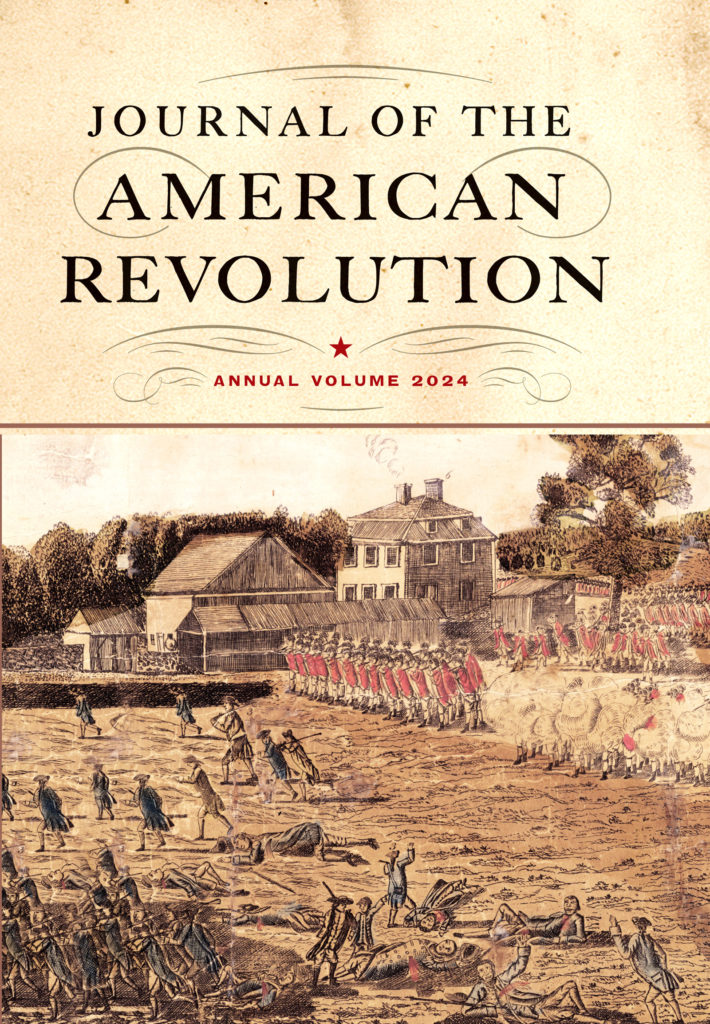

(The photograph above shows the

Van Wyck Homestead, once the administrative center for the supply depot and now the only surviving structure from that large complex. It’s a New York state

museum.)