“There are always joys while going through manuscripts”

Ptolemy, who’s on the staff of the William L. Clements Library in Ann Arbor, wrote:

The Clements holds the papers of Charles Townshend (1725-1767), who served as Secretary of War during the Seven Years’ War and the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the decades leading up to the American Revolution. These days, he is mostly known as the straw man for incendiary British taxation policies due to his role in sponsoring the infamous Townshend Acts.“The Record Scratch” is a fine metaphor for that moment, though I don’t think it gives a good sense of the rest of this article.

Internally at the library, however, we mostly grumbled about him under our breath because his papers were in a complicated arrangement, the finding aid was difficult to navigate, and the boxes even harder to pull for researchers. It needed someone to puzzle out what was in each box and add descriptive information to the finding aid to make it more manageable. Unfortunately, I don’t have a penchant for economic history, so figuring out how to describe the contents of “Miscellaneous Treasury Papers” meant trying to disambiguate a great many reports on tariffs, duties, and excises.

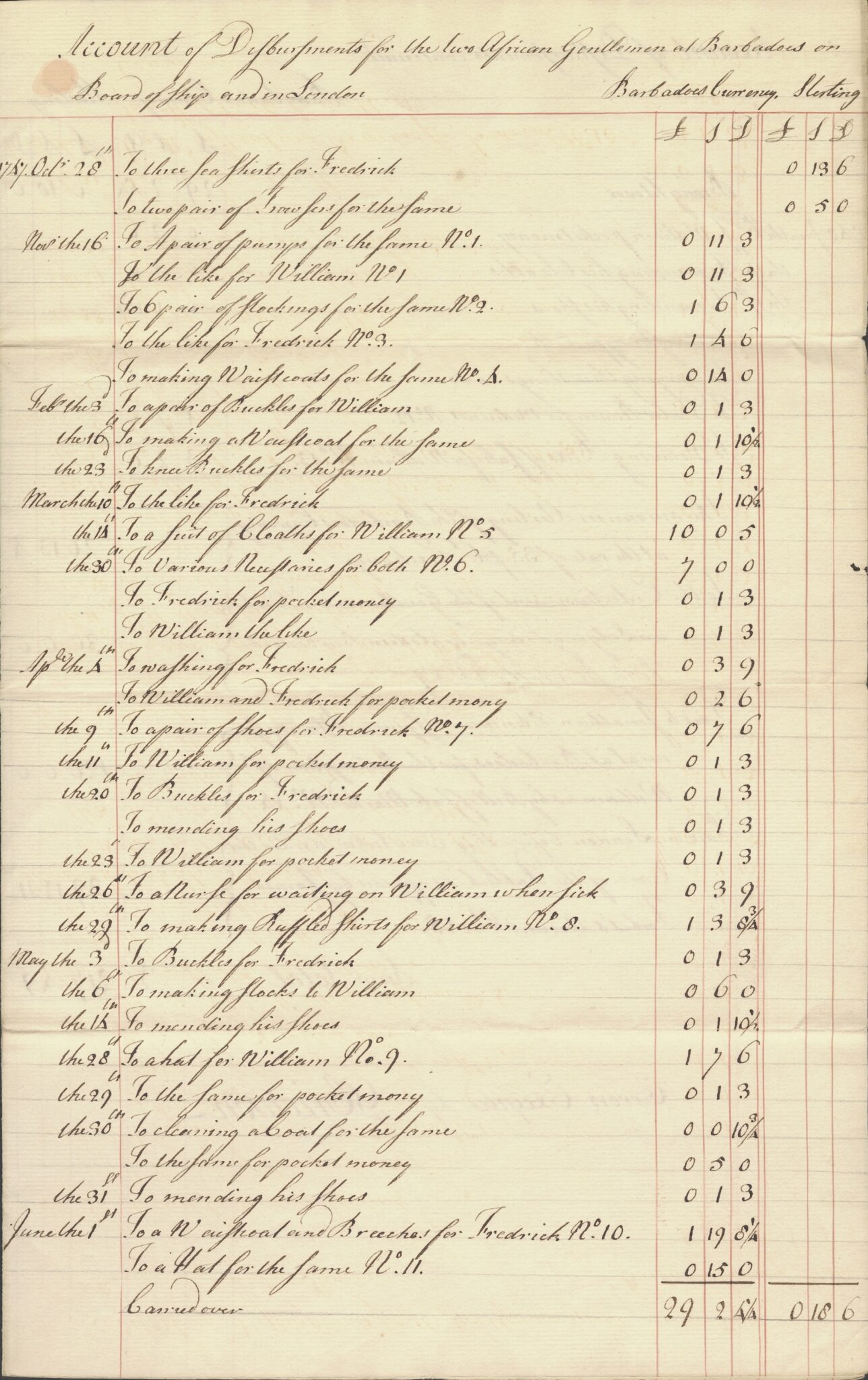

There are always joys while going through manuscripts—an unexpected doodle, a funny quote, beautiful papers—but most of what I was encountering was financial document after financial document–Until one stopped me right in my tracks. It referred to expenses “for the two African Gentlemen at Barbadoes.” Written in 1747, the use of “Gentlemen” to describe African peoples was eye-catching enough, but glancing down at the accounts, the entries for making waistcoats, providing pocket money, buying ruffled shirts, and more signaled something extraordinary. . . .

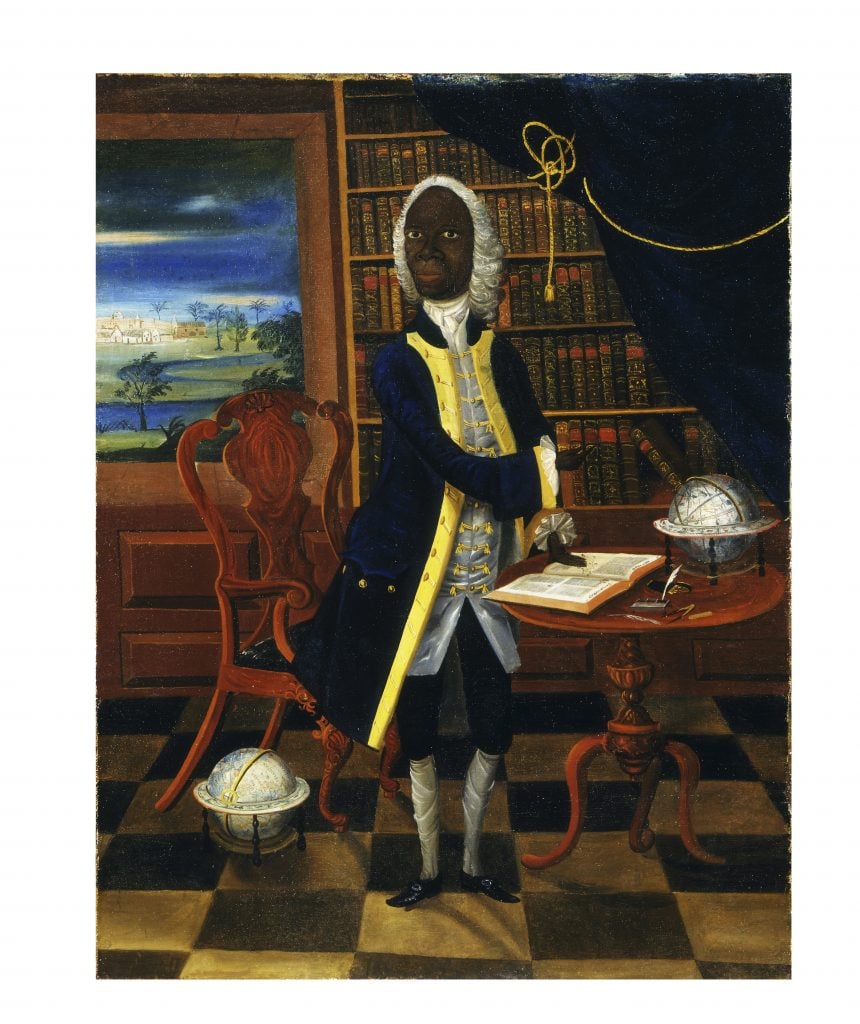

And then, a document written from Bridgetown, Barbados, laid it all out:Whereas John Corrantee and the Caboceers of Annamabo are at present exceedingly well disposed towards the British Nation, and beg the resettlement of that place by the English, and the fort to be rebuiltOH.

And whereas a Son of John Corrantee’s Named Ansah was sold here by Captain Hamilton who he (Corrantee) is very anxious to have redeemed

We hereby give it as our Opinion that the Redemption of the said Ansah will be very acceptable to John Corrantee (who is the leading man at Annamabo) . . . and will be a means to conciliate Corrantee to, and rivet him in the Interest of the British Nation in opposition to the French, who have been aiming for some Years past at the aforesaid settlement.

OH NO.