Where Did Lucy Flucker and Henry Knox Marry?

The next week’s newspaper reports confirm that the rector of that church, the Rev. Dr. Henry Caner, presided at the wedding.

There’s another disagreement about that marriage, however: where it took place. Writers have come to different conclusions.

The most likely site would seem to be King’s Chapel itself. Nothing in its records suggests the Knoxes’ wedding was any different from others. Most biographers who describe the ceremony state that it happened in the chapel.

However, in The Revolutionary War Lives and Letters of Lucy and Henry Knox Phillip Hamilton wrote that the marriage took place in the building on Cornhill that Henry was renting as his house and shop. Lucy’s older sister Hannah Urquhart and “Aunt Waldo” attended, but her parents didn’t.

Hamilton appears to have relied on Henry Knox’s 29 August letter to his close friend Henry Jackson, which I haven’t seen in full. It’s now in the collection of the Gilder Lehrman Institute. Barring new discoveries, that’s the closest contemporaneous source about the young bookseller’s strained relationship to his new in-laws.

There are also a couple of memoirs written in the nineteenth century by members of the extended family that preserve their understandings about the marriage.

The Massachusetts Historical Society holds a manuscript called the “Winslow Family Memorial.” It was written by Isaac Winslow (1774–1856), a first cousin of Lucy Knox, and his daughter Margaret Catharine Winslow (1816–1890). The oh-so-handy transcript (P.D.F. download) offers this story of the marriage:

they were married at the house of her uncle Mr [Isaac] Winslow in Roxbury. I always understood, that he rather favor’d this union, and aided in its favorable issue. For this friendly disposition Gen Knox, as I have been led to think, from the little I know of the circumstances of the case, evinced more grateful feeling’s towards Mr Winslows family than his lady, who though not unkind to her cousins, yet when living in a good deal of style, after the peace in Boston, did not much notice her cousins, who were then in quite narrow circumstancesHamilton’s citations show he looked at this manuscript, but he didn’t accept its statement that the Knox wedding took place in Roxbury.

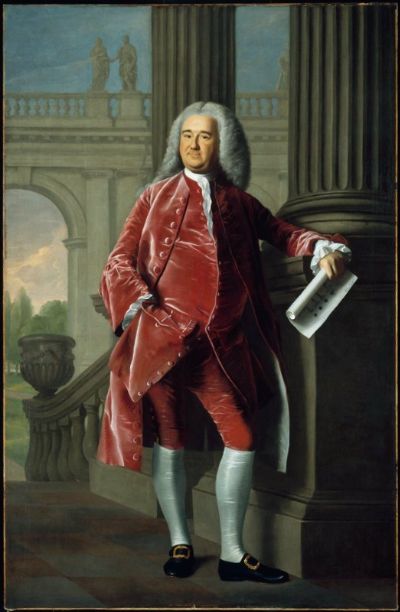

Finally, the “Reminiscences” of the Knoxes’ longest lived daughter, Lucy Knox Thatcher (1776–1854, shown above), is held at the headquarters of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution in Washington, D.C. Nancy Rubin Stuart quoted from it in Defiant Brides. It agrees that Lucy’s parents didn’t attend the wedding but says her sister Hannah and their half-sister Sallie did. Again, I’ve seen only a bit of this document and plan to check it out on a future trip.

(The portrait above shows Lucy Knox Fletcher in the mid-1800s. Because there’s no portrait of Lucy Knox, and because of the similarities of the mother’s and daughter’s names, websites often mistakenly present this as a picture of Henry Knox’s wife.)