Thomas Newell and “that Detestable Tea”

But what did Newell do to support that stance?

On 17 November the young man made clear he didn’t participate in the attack on the Clarke family’s warehouse, discussed back here: “This evening a number of persons assembled before Richard Clarke’s, Esq., one of the consignees of tea; they broke the windows, and did other damage. (I was at fire meeting this evening.)”

On 2 December, the same day Capt. Bruce arrived, Newell’s diary contains one of the longer bits of cipher in the diary. The word “Junr” is legible among the little symbols, and a squiggle that doesn’t fit the cipher turns out to be “St.” What was Newell hiding?

Not a whole lot, it turns out. Once deciphered, the line reads: “This Eving. was at St. Andrew’s Lodge, I was chosen Junr Deacon of said Lodge.” Well, good for Thomas Newell.

Some people credit that lodge of Freemasons with being at the heart of the anti-tea operation. (None give it more credit than the lodge itself.) And indeed Newell got more involved the next night.

On 3 December, Newell recorded: “This evening I was one of the watch on board of Captain Bruce (with twenty-four more), that has tea for the Clarkes & Co.” That patrol was to keep the tea from being landed so the tax could be collected.

Finally, here’s Thomas Newell’s account of 16 December:

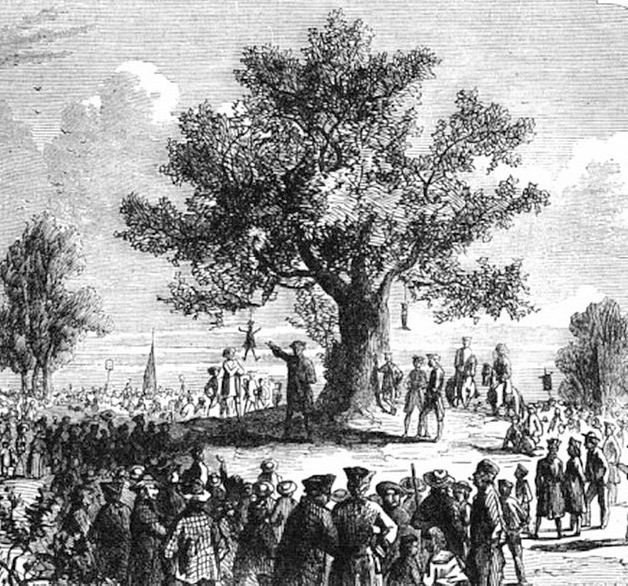

Town and country sons mustered according to adjournment. The people ordered Mr. [Francis] Rotch, owner of Captain [James] Hall’s ship, to make a demand for a clearance of Mr. [Joseph] Harrison, the collector of the custom house (and he was refused a clearance for his ship). The body desired Mr. Rotch to protest against the custom-house, and apply to the governor for his pass for the castle. He applied accordingly, and the governor refused to give him one. The people, finding all their efforts to preserve the East India Company’s tea, at night dissolved the meeting. But behold what followed the same evening: a number of brave men (some say Indians), in less than three hours emptied every chest of tea on board the three ships, commanded by Captains Hall, Bruce, and [Hezekiah] Coffin (amounting to 342 chests), into the sea.Was Newell among those “brave men”? I’d guess not. But he surely knew some of them.

A couple of details struck me Newell’s writing about the Boston tea protesters. First, he consistently referred to the people meeting in Old South Meeting-House as ”sons of liberty.” He didn’t worry about calling them the “body of the people.”

Second, in Newell’s telling the crowd that afternoon was trying “to preserve the East India Company’s tea.” By having it shipped back to Britain, that is. Would be a shame if anything else happened to it.

TOMORROW: A mystery name.