“Richard Fry, Stationer, Bookseller, Paper-maker, and Rag Merchant”

Another Boston merchant, Samuel Waldo (1696-1759, shown here) also saw potential in paper. He made a partnership with Thomas Westbrook (1675–1744) of the district of Maine, securing title to a large swath of land between the Penobscot and Muscongus Rivers. Waldo headed to Britain to recruit skilled craftsmen while Westbrook set about building a settlement to receive them.

One of the men Waldo met in England was Richard Fry. According to A. H. Shorter’s Paper Making in the British Isles (1971), Fry, a “rag merchant,” paid to insure a paper mill at Long Wick in Buckinghamshire in 1726. John Bidwell’s American Paper Mills (2013) adds that Fry oversaw two more paper mills in Berkshire and owned part of a paper warehouse in London. Bidwell also reported that in 1730 Fry went bankrupt, and thus at liberty to make a new start in America.

Fry and Waldo signed an indenture contract in 1731. Fry promised to move to New England, and Waldo promised that within ten months Westbrook would finish building a paper mill on their land in Maine for Fry to run.

Richard Fry reached Boston by the end of that year. He had to support himself for a while, so in April and May 1732 he ran the same advertisement in the New-England Weekly Journal, Weekly Rehearsal, and Boston Gazette:

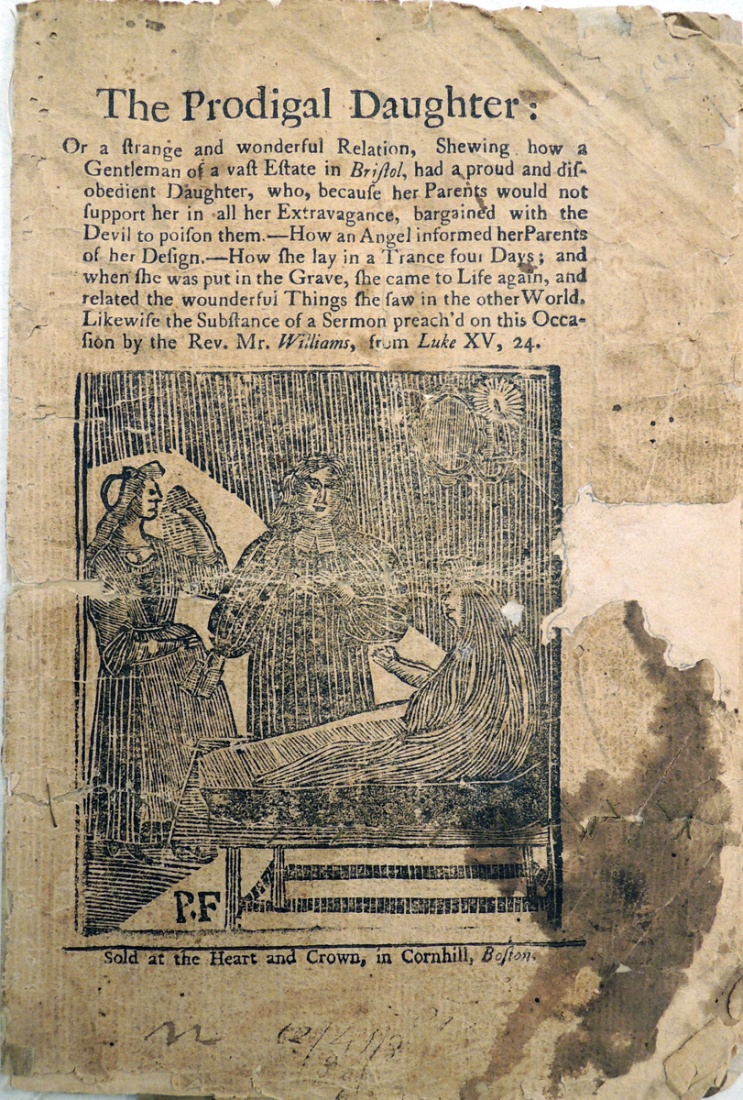

This is to give Notice, That Richard Fry, Stationer, Bookseller, Paper-maker, and Rag Merchant, from the City of London, keeps at Mr. Thomas Fleet’s Printer at the Heart & Crown in Cornhill, Boston; Where the said Fry is ready to accommodate all Gentlemen, Merchants, and Tradesmen, with sets of Accompt Books, after the neatest manner: And whereas, it has been the common Method of the most curious merchants in Boston, to Procure their Books from London, This is to acquaint those Gentlemen, that I the said Fry, will sell all sorts of Accompt-Books, done after the most acurate manner, for 20 per Cent. Cheaper than they can have them from London.I haven’t found any “former Advertisement.” If Fry had indeed collected 7,000 pounds of rags and sold 1,200 copies of the Duck poetry collection, most of that work might have been in Britain. The Boston print shop of Kneeland and Green did issue Duck’s Poems on Several Subjects in 1732, but it’s not clear whether they were working with Fry or inspired by him.

I return the Publick Thanks for following the Directions of my former Advertisement for gathering of Rags, and hope they will continue the like Method; having received seven thousand weight & upwards already.

For the pleasing entertainment of the Polite part of Mankind, I have Printed the most Beautiful Poems of Mr. Stephen Duck, the famous Wiltshire Poet: It is a full demonstration to me that the People of New England, have a fine taste for Good Sense & Polite Learning, having already Sold 1200 of these Poems.

On 29 May, Fry announced another scheme in the New-England Weekly Journal:

This is to Acquaint the Publick, that I have Printed a Specimen of a new Sett of Letters, lately Imported from London, on which I propose to print the Spectators by Subscription, at Three Pounds the Sett, neatly Bound; and that the Publick may be intirely satisfied, the Subscriptions in Boston are to be taken in at the Office of Mr. Joseph Marion, Notary Publick, & Deposited in his hands.Unaccountably, Fry’s type sample and hortatory advertisement didn’t bring in three hundred subscriptions, and he never printed the Spectator.

It will be needless to acquaint the Learned and Polite part, that nothing more demonstrates the fine Genius of a Country, than to have the curious Art of Printing brought to Perfection, wherein the present Age have Opportunity to convey their Ideas in fine Characters to succeeding Ages. The vast Returns the Dutch make only in this Branch of Trade is most prodigious, for they Print for all the Known parts of the World; and it was really the Grand Oppressions they suffer’d that gave them that Keen Edge, to such a pitch of Industry, as hath brought them to make that glorious Figure they now make in the World: Therefore the Rod is sometimes very Convenient to reform Common-wealths of those things which would certainly be destructive of their Happiness: and there is no way of bringing any Common-wealth out of any Calamity but Industry, and jointly to promote every Art and Science that has the least view of being useful to the Publick: Therefore I don't doubt but every Gentleman that is a true Lover of his Country will Subscribe.

And I justly flatter my self I shall have a Number of Ladies Subscribers, the Authors of these Books having always been justly esteem'd among them.

Richard Fry.

N.B. Subscriptions will be taken in at Newport, New-York, Philadelphia, Piscataqua, and South-Carolina, and after Three Hundred Subscriptions, the work to be committed to the Press, and finish’d with all possible Expedition. 20 s. to be paid at Subscribing, & 40 s. at Delivery.

Meanwhile, Westbrook was still building up in Maine. The paper mill wasn’t finished within ten months. In fact, the building wasn’t ready for Fry to move in until 1734. He then signed a twenty-one-year lease, promising Waldo and Westbrook £64 sterling each year.

TOMORROW: The Brazen Head connection.