“Quite exasperated with your conduct relating to your amour”

As the year 1750 began, it was more than three years since Andrew Pepperrell and Hannah Waldo had become engaged, over a full year since their intentions had been formally announced in Kittery, Maine.

Since their fathers were two of the richest, most prominent men in Massachusetts, their relationship was big news all that time.

Andrew and Hannah had both turned twenty in 1746, young for marriage. But by 1750 they would both turn twenty-four, they still weren’t married, and the talk became more pointed.

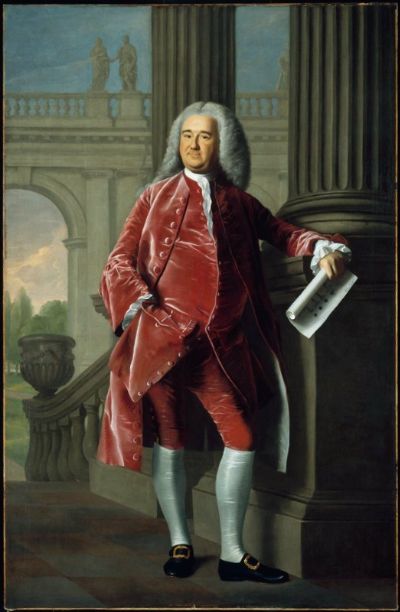

Andrew’s brother-in-law Nathaniel Sparhawk (shown here) wrote to Sir William Pepperrell in London on 8 Mar 1750: “The love affair between Andrew Pepperrell and Miss Waldo, now of four years’ duration, is still pending, much to the annoyance of both families as well as trying to the patience of the young lady.”

Other gentlemen told Pepperrell that he couldn’t keep putting off the wedding. The older merchant Stephen Minot, who was related to the Waldos, wrote to him on 3 June 1750:

Sparhawk visited Andrew Pepperrell in Maine late that summer, and on returning to Boston wrote back on 11 September:

All that pressure forced Andrew Pepperrell to finally make a move. He agreed to a wedding in Boston on a specified date.

TOMORROW: Can this marriage be saved?

Since their fathers were two of the richest, most prominent men in Massachusetts, their relationship was big news all that time.

Andrew and Hannah had both turned twenty in 1746, young for marriage. But by 1750 they would both turn twenty-four, they still weren’t married, and the talk became more pointed.

Andrew’s brother-in-law Nathaniel Sparhawk (shown here) wrote to Sir William Pepperrell in London on 8 Mar 1750: “The love affair between Andrew Pepperrell and Miss Waldo, now of four years’ duration, is still pending, much to the annoyance of both families as well as trying to the patience of the young lady.”

Other gentlemen told Pepperrell that he couldn’t keep putting off the wedding. The older merchant Stephen Minot, who was related to the Waldos, wrote to him on 3 June 1750:

I hope, my friend, it will not be long before we have the pleasure of seeing you in town to disappoint the enemies as well as to complete the approaching pleasure which you have in view, in enjoying the society of so charming and desirable a lady as is Miss Hannah. I beg leave only to add, that could you be fully acquainted with the steady and proper behavior in your long absence (amid the ill-natured queries of the world with respect to each of you) it would ever heighten your affections for her, and endear her to you as it has done to me, and all her relations and friends here. I really wish each of you, as I believe you will be, happy, if it shall please God to bring you together in the matrimonial state.On 14 August, Andrew’s first cousin William Tyler wrote to him about a visit to Boston by another first cousin, Joel Whittemore. “His wig was powdered to the life,” Tyler said, and at the Sunday afternoon church service “he sat and stood looking first this way and then that way to find out Miss Hannah.” (She wasn’t there.) Was that just a silly story, or a nudge that other young men might be interested in her?

Sparhawk visited Andrew Pepperrell in Maine late that summer, and on returning to Boston wrote back on 11 September:

I…have not had time to deliver your letter, or to see your lady. Let me take the liberty to inform you that the country, especially the more worthy and better part of it, are very much alarmed at, and appear quite exasperated with your conduct relating to your amour, and your friends and those that are much attached to your father and family, are greatly concerned about you, being fully of opinion that if the matter drops through and you lie justly under the imputation of it, that your character is irretrievably lost. I am sorry to say so much, but a tender concern for you obliges me.Massachusetts couples who were eloping from their families, or who needed to marry in a hurry, went over the border to New Hampshire. Of course, that wasn’t the most respectable sort of wedding. But by this time, Sparhawk and the Waldos were ready for anything.

You can’t imagine how I was attacked in a large company of gentlemen and ladies at Salem, where I was invited to spend the evening on Sunday; and what you may imagine will pass still for a justification of your conduct, that you “intend nothing but honor in the case, and will be along soon” is perfectly ridiculed.

I find you must be published again if you marry in this province, and if you intend ever to marry the lady, my advice to you is, by all means to be republished and to finish the matter at once, unless you can prevail on the lady to meet you at Ipswich, and from there proceed to Hampton [New Hampshire], which is very much questioned, though when I know your intentions it may be attempted, if there is occasion, from your ascertaining the lady’s mind and her friend’s, that you will be quite punctual, and agree to the arrangement in case she is good enough to comply. But I cannot add further than that I feel a real concern for your welfare and the support of your honor.

All that pressure forced Andrew Pepperrell to finally make a move. He agreed to a wedding in Boston on a specified date.

TOMORROW: Can this marriage be saved?