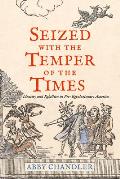

Chandler on Stamp Act Protests in New England, 1 Nov.

As Chandler explained in an interview at the Journal of the American Revolution:

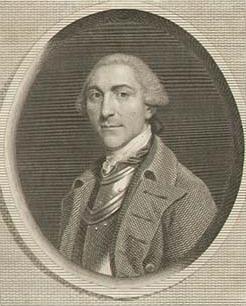

My original plan was to write a biography of Martin Howard who was a Loyalist from Rhode Island who later became the Chief Justice of North Carolina. He refused to disavow his loyalty to Britain in Rhode Island in 1765 and again in North Carolina in 1777 and had to flee for his life both times.So Chandler’s book became a study of the political movements swirling around Howard. Both Rhode Island and North Carolina were overshadowed by large neighboring colonies that became known for leading resistance to the Crown. Yet arguably each of those smaller colonies saw more resistance to authority in the pre-war period. And they were also the last two holdouts against the Constitution.

The reason I found him interesting was because the arguments that he made for supporting the British Empire are rooted in the same political traditions used by the men who argued in favor of revolting against the British Empire. . . .

The problem, however, with studying a man who had to abandon everything twice and died in exile is that he left very few documents explaining his thought processes.

For the North Andover Historical Society, Chandler will focus on the Stamp Act protests of 1765, and how the movement in Rhode Island played out. While the Crown had appointed Francis Bernard to be governor of Massachusetts, and he felt a duty to enforce the new tax, Rhode Island elected Gov. Samuel Ward. He refused royal instructions to uphold that law. While Bostonians targeted the house of the appointed lieutenant governor, Thomas Hutchinson, in August 1765, Newporters had to find a different sort of target for their wrath—which is where Martin Howard comes in.

Abby Chandler is a professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. She serves on the 250th American Revolution Anniversary Commission in Massachusetts. I’ve had the pleasure of hearing her speak at many forums, most recently this summer’s History Camp Boston.

This talk is scheduled to start at 7:30 P.M. in the Stevens Center on the Common, 800 Massachusetts Avenue, North Andover. Register through this site.