“Statement of account of Gouverneur Morris”

Morris succeeded Thomas Jefferson as the U.S. of A.’s minister to France in 1792, having been in that country since 1789. He therefore got to see the French Revolution.

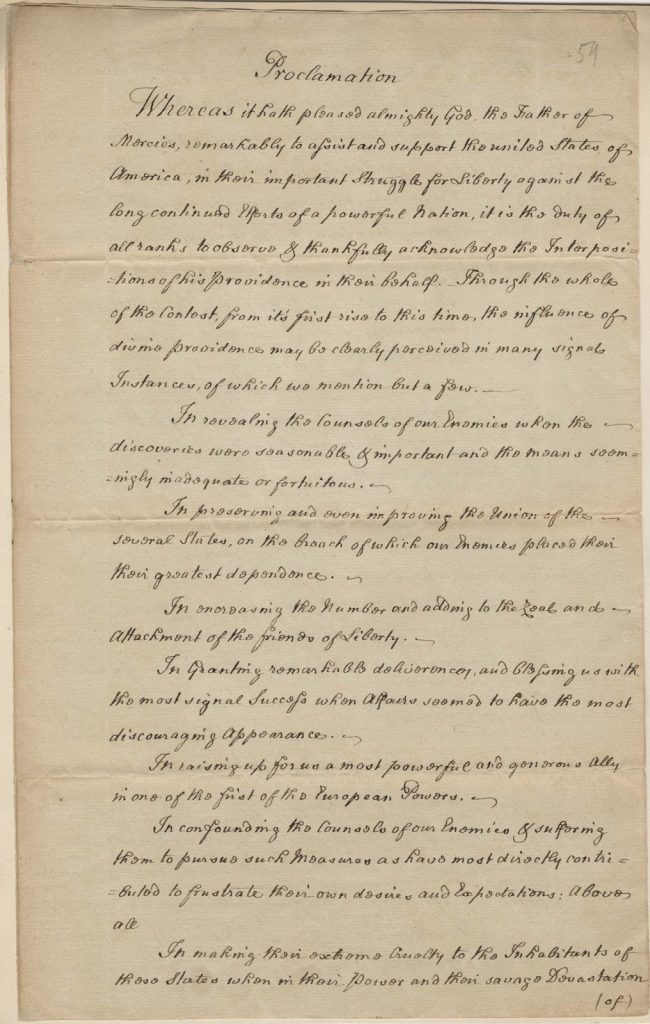

What’s more, these documents show, Morris got involved.

Labeled simply as a “statement of account of Gouverneur Morris, July-September 1792,” the paper is a record of the money Morris agreed to receive from Louis XVI to raise a counter-revolutionary force when it became clear that the monarchy was in danger of violent overthrow. This was a remarkable episode—while he was U.S. minister, Morris conspired with some of Louis’s loyal counselors to try to save the monarchy and help the royal family escape. . . .Founders Online currently hosts the papers of seven prominent men involved in forming the American republic, with John Jay the most recent addition. Though as a Bostonian I should root for Samuel Adams to be added to that list, I can’t help but think that Gouverneur Morris’s papers would be so much more fun.

Another group of items that I was delighted to find relate to the much-admired Marquis de Lafayette, whom Morris knew during the American Revolution and saw again in France. The letters came from Morris’s close friend and business partner, James LeRay de Chaumont. They discuss LeRay’s efforts to obtain repayment of an enormous personal loan Morris made to Lafayette’s wife at her request, to cover their “debts of honor” after the Marquis—whose fall from leader of the Revolution to being considered a traitor had been swift, just as Morris had predicted— fled France and was imprisoned by the Austrians. Our research for Morris’s later diaries (1799-1816) originally led us to the tentative conclusion that Morris had never been repaid. These letters confirm it. His later financial difficulties were considerably exacerbated by this default.

It was acknowledged by her family and others that Morris saved Mme. de Lafayette from the guillotine during the Great Terror, and his diaries show that his efforts led to the Austrian emperor’s decision to release the Marquis in 1797. A letter from LeRay, who met with Mme. de Lafayette in Paris more than once after she and her husband returned to France and were restored to their estates, confirmed what I could only infer from Morris’s letters: that Madame de Lafayette (who had never forgiven Morris for speaking truth to her husband in the early days of the Revolution) seemed outraged that Morris had the nerve to request repayment…