Daniel George was born in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on 16 Dec 1757, son of David and Anne (Cottle) George. He was the second boy named Daniel born to that couple, indicating that the first had died young. He had both older and younger siblings of both sexes.

From infancy Daniel was “a Cripple,” possibly having cerebral palsy. That made life as a farmer almost unthinkable. But the boy’s mind was sharp, and he took to mathematics and then astronomy. In 1775, Daniel prepared an almanac for the upcoming year, calculating the movements of the Sun and Moon and the tides for eastern Massachusetts.

On 26 August, Daniel George and his father visited the Rev.

Samuel Williams (1743-1817) of

Bradford. Williams was known for his

scientific investigations, including two trips to observe the transit of Venus in the 1760s.

Williams talked with the teenager and wrote a recommendation of him to the

printer Ezekiel Russell, then in

Salem:

Mr. David George, of Haverhill, is now with me; he has brought his son Daniel, who appears to be a singular object of pity and compassion. But with all the disorders of body under which he labors, his mind does not seem to have been at all affected. He has composed an Almanack, which, as far as I have inspected it, seems to be equal to other compositions of that kind; and perhaps from the singular situation of the Author, bids fair to engage the popular attention. If it would be consistent with your business and interest to print it, it would be an act of kindness to the distressed, and a great encouragement to a rising Genius, in early years laboring under uncommon disadvantages, but yet bidding fair for very considerable improvements.—

I write this from motives of compassion to the unhappy Cripple, and because I really think his talents may be of use to mankind if encouraged. How far this will be consistent with your interest is not for me to say. But if you can favor the productions of a Cripple, in the seventeenth year of his age, it must not only give pleasure to him, but to the benevolent and humane who wish success to the ingenious, and comfort to the wretched.

Russell was open to new authors: he was the first printer to engage to issue

Phillis Wheatley’s book, before she went to London, and he routinely published other female poets, such as

Hannah Wheaton. In part that was because Russell was never a very successful printer, so he and his wife were often scrounging for business.

Russell engaged to print

George’s Cambridge Almanack; or, the Essex Calendar. For the Year of our Redemption, 1776. Being Leap-Year, the Sixteenth of the Reign of George III. To make sure customers realized what a remarkable production it was, he credited it “By Daniel George, a Student in Astronomy at Haverhill, in the County of Essex, who is now in the Seventeenth [sic] Year of his Age, and has been a Cripple from his Infancy.” And he printed Williams’s letter at the front.

In his own introduction, dated September 1775, Daniel added:

This, however, my public-spirited Friends and Countrymen, you will be certain of, by becoming a Purchaser of my Almanack, you are helping one who is not able, or perhaps ever will have it in his power to help himself; which motive alone may be a sufficient incitement to a generous mind, even should your expectations with regard to my calculations, be in some measure disappointed.

But he then turned to the patriotic material he’d chosen to include, such as “A Narrative of the excursion and ravages of the

King’s troops, under the command of Gen. [

Thomas] Gage, on the 19th of April, 1775; . . . This concise and much admired narrative is said to be drawn up by the reverend and patriotic Mr. G——n, of the third parish in

Roxbury.” (I believe that’s one of our earliest pieces of evidence that the Rev.

William Gordon drafted that report for the

Massachusetts Provincial Congress.)

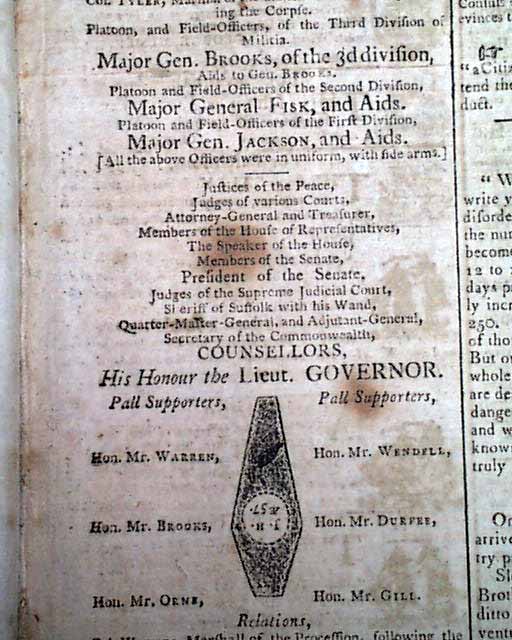

The calendar pages inside highlighted such anniversaries as:

- “Feb. 21 [actually 22]. Christopher Snyder, aged 14 [actually about eleven], cruelly massacred in Boston, by Ebenezer Richardson, the noted informer. He was the first Martyr to American Liberty.”

- “March 5. Boston massacre.”

- “April 19. Concord Fight, 1775, when began the bloody civil war in America, by the British Troops.”

- “June 17. Bloody battle of Charlestown, where were killed and wounded 324 provincials, 1,450 regulars; there were destroyed in Charlestown by the latter 1 meeting-house, 350 dwelling-houses, and 150 other buildings.”

- “Dec. 16. E. I. Tea destroyed in Boston, 1773.”

And all for only “6 cop.”

George’s Almanac sold well enough that Russell issued a second edition with added content: a “Narrative of the Bunker-Hill Fight” and “A Poem On The Late Gen. [

Joseph] Warren.” But wait—there was more! The extra page also included “An Acrostic On Gen. Warren” (the same one I

quoted here) and a woodcut portrait of the late doctor (shown above).

The next year Daniel, still a teenager, prepared an almanac for 1777 for new printers in Boston and

Newburyport. Having established his name, he continued to publish almanacs into adulthood. Sometime in the mid-1780s he moved to what is now Portland,

Maine, and eventually became a newspaper publisher.

In

The History of the Press of Maine (1872), H. W. Richardson wrote:

George was a remarkable character. He is described as a man of genius, but so exceedingly deformed that he had to be moved from place to place in a small carriage, drawn by a servant. He came here in 1784 or ’5 from Newburyport, where he had published almanacs, as he afterwards did here. He was a printer, but kept school in Portland, and had also a small bookstore in Fish, now Exchange, street. In 1800 he became the sole owner of the Herald.

George “died suddenly at Portland” on 4 Feb 1804, age forty-six, having seen and accomplished much more than anyone expected back in 1758, the year when the George family probably realized that their new baby had a physical disability.