How the Massachusetts Press Responded to the 1783 Earthquake

First, we’re used to a standard time extending across an entire time zone. But before railroads, every town had its own noon, and therefore its own perception of when something big happened.

The Massachusetts Gazette and General Advertiser in Springfield said this earthquake was felt “at 40 minutes past 10 o’clock.” The Boston Gazette reported it at “about six minutes before eleven o’clock.” And the Salem Gazette pegged it “at about 11 o’clock.” Of course, it took a few seconds for the shock to travel between those places. The big difference in those times came from how the Earth spins.

All those reports appeared in the first week of December. Starting on 8 December, Massachusetts newspapers began reporting on other places people detected the quake. Printers wondered if it wasn’t as small an event as it first seemed. On 12 December, the Salem Gazette said the shaking was definitely worse in Connecticut and New York.

By 18 December, the newspapers from Philadelphia had arrived, and Massachusetts printers could share details from nearer the epicenter in New Jersey. China and pewter thrown off shelves! People woken from sleep! Aftershocks later the same night!

Still, there were no deaths. Earlier in the year, American newspapers had reprinted news of many people dying from earthquakes in Italy, and similar reports from China.

Isaiah Thomas’s Massachusetts Spy editorialized:

This year must make a conspicuous figure in the instructive records of Time: Great revolutions have occured in the natural and political world.The Salem Gazette’s 12 December follow-up to its first report ran just above a local disaster with real damage: A fire in John Piemont’s barn in Ipswich had killed one cow and consumed all his hay for the winter.

In Europe the convulsions of nature have destroyed a great part of Sicily, &c. with about one hundred thousand inhabitants. In America such events have taken place, as were before unknown to its civilized inhabitants.

What gratitude is due from us to heaven for its Benedictions—Independence, as a Nation, with the blessings of Peace; and that we have not in the first transports of our national existence met with those calamities that might in a moment have reduced our Continent to its original Chaos!

Back in 1770, Piemont was a hair stylist at the center of Boston, and at the center of Boston events, as I discussed back here. He was able to bounce back from this fire, and in 1784 advertised that he once more offered a stable for horses.

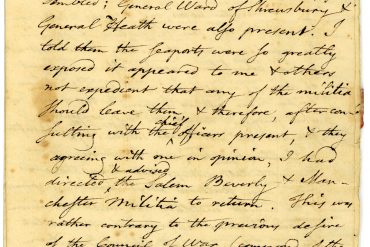

(The broadside shown above dates from almost thirty years after this quake.)