Jacob Francis (1754-1836) was a

Continental Army soldier known almost entirely through his pension application, filed in 1832.

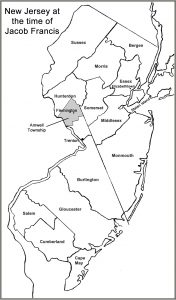

In this document Francis testified that he was born in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, to a

black woman. It’s not clear whether he was ever legally

enslaved, but as a

child he was definitely in some form of bondage. Jacob described serving in turn Henry Wambaugh [a

German immigrant, 1720-1787], Michael Hatt, Minner Gulick [documented elsewhere as Minnie Gulick, 1731-1804], and Joseph Saxton. He took the surname Gulick from his third master.

Starting in May 1768, Saxton took his servant boy to Long Island,

New York; the

Caribbean island of St. John; and

Salem, Massachusetts. There in 1769, Jacob recalled, a man named Benjamin Deacon bought the time remaining until he turned twenty-one. So at least at that point Jacob’s masters were treating him as an indentured apprentice rather than a slave.

In January 1775 Jacob Gulick became free. That October, he enlisted in the Continental Army regiment of Col.

Paul Dudley Sargent. He recalled his captain’s name as “Wooley, or Worley, or Whorley,” and that other men from the same family served as officers and a drummer. That captain was therefore John Wiley (d. 1805), who served from early 1775 through January 1781, ending as a major.

Gulick’s enlistment is interesting because at that time the

Continental Congress, steered by Gen.

George Washington and most of his generals, had barred all men of African ancestry from enlisting in the army. We know, however, that officers were anxious to fill their companies with anyone willing to serve for the full year of 1776. Some of Washington’s officers helped to convince him to change his mind about the army policy at the end of December 1775.

Pvt. Gulick served with Col. Sargent’s regiment at the Battle of

Brooklyn and the Battle of

Trenton and the retreats in between. At the end of his enlistment in January 1777 he was in New Jersey, so he went back to Hunterdon County and found his mother. She told him about his father, and thereafter he went by Jacob Francis.

Pvt. Francis served several short tours in New Jersey regiments across the remainder of the war. One of his captains was Philip Snook (1745-1816), whose older sister Ann was the wife of Francis’s first master, Henry Wambaugh.

In 1789 Jacob Francis married “Mary, a servant of Nathaniel Hunt.” He bought her freedom, and they had several children. By 1800, the family was settled in the Hunterdon County village of Flemington. For the fiftieth anniversary of U.S. independence, Francis participated in a parade of local Revolutionary veterans. He and another “colored” man, Lewis English, were listed separately from the white soldiers in an 1880 description of the event.

In 1832, at the age of seventy-eight, Jacob Francis applied for a pension as a Revolutionary soldier, narrating his service. It was approved, and he received payments for four more years. Mary Francis applied for a widow’s pension after that.

The 5 Aug 1839

Newark Daily Advertiser picked up this death notice from the

Flemington Gazette:

Another Hero of the Revolution.—In this village, on Tuesday the 26th of July, JACOB FRANCIS, a colored man, in the 83d year of his age. He has resided in this place thirty-five years; has been an orderly member of the Baptist Church for thirty years; he has raised a large family, in a manner creditable to his judgement and his Christian character, and lived to see them doing well; and has left the scenes of this mortal existence, deservedly respected by all who knew him.

Jacob Francis was a soldier of the Revolution—he served a long tour of duty in the Massachusetts militia, and was some time in the regular army in New Jersey; and we have learned from those who knew him in those days of privation of peril, that his fidelity and good conduct as a soldier were the object of remark, and received the approbation of his officers.

For the last few years he received a pension from the government; an acknowledgement of his services to his country which, though made at a late day, came most opportunely to minister to his comfort in the decline of life, and under the infirmities of old age.

This was by far the longest death notice in that issue of the

Daily Advertiser, and it was reprinted at least as far away as Cleveland.

TOMORROW: Pvt. Francis’s story of Gen. Putnam.