Francis Williams, Man and Symbol

After digging a bit more, I found that only one of those webpages—the first, from the Victoria & Albert Museum—is informed by Prof. Vincent Carretta’s article “Who Was Francis Williams?” published in Early American Literature in 2003. That provided a valuable corrective to what had been written about Williams since shortly after his death.

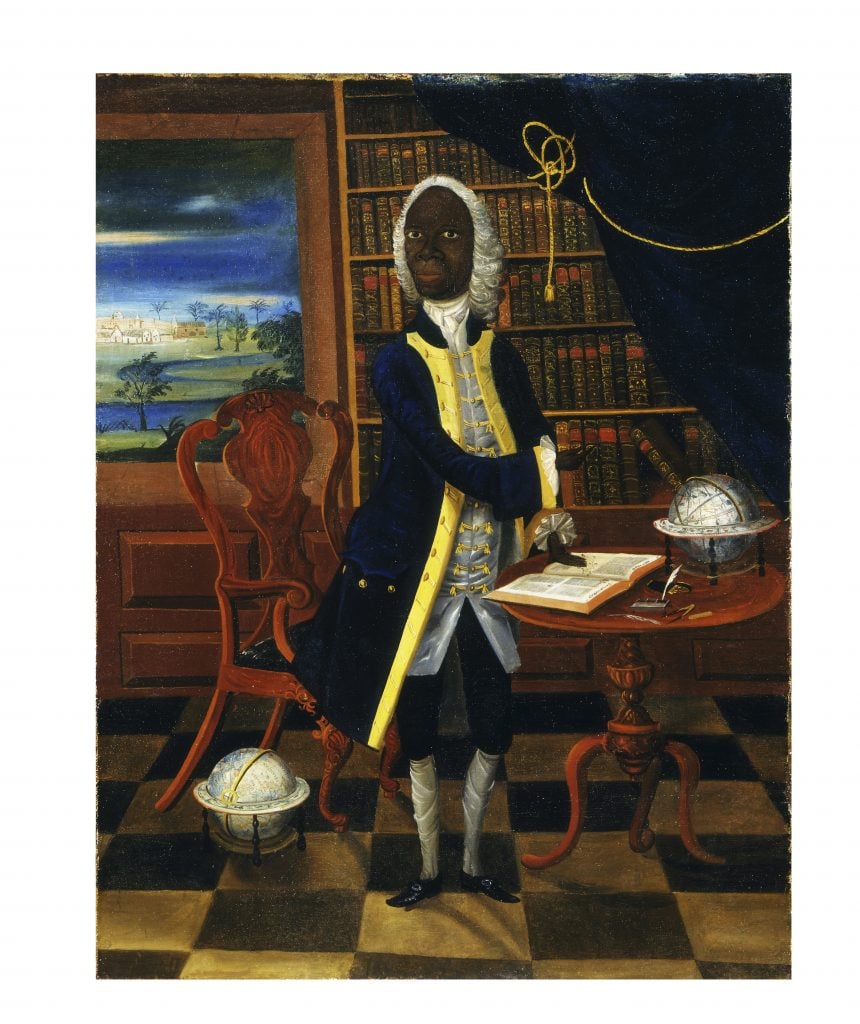

Most of our previous information about Williams came ultimately from Edward Long’s History of Jamaica (1774). That book includes an inaccurate capsule biography, one of Williams’s poems, and the argument that he hadn’t really accomplished much. Long was hostile to the idea of an intelligent, educated, property-owning black man, so why did he mention Williams at all? For one thing, he seems to have been fascinated by the man at some level; the portrait above came down in Long’s family.

More importantly, when Long wrote, Williams had already become a minor celebrity. Anti-slavery authors used him as an example of how people of blacks could succeed very well given a fair chance at education and wealth, and white supremacists struggled to denigrate his accomplishments. Among the writers mentioning (or presumably mentioning) Williams were:

- Dr. Alexander Hamilton, in his “Itinerarium” of 1744 (not published until 1948): “There, talking of a certain free negroe in Jamaica who was a man of estate, good sense, and education, the ’forementioned gentleman…asked if that negroe’s parents were not whites, for he was sure that nothing good could come of the whole generation of blacks.”

- David Hume, in “Of National Character” (1748): “In Jamaica, indeed, they talk of one Negro as a man of parts and learning; but it is likely he is admired for slender accomplishments, like a parrot who speaks a few words plainly.”

- The editors of The Gentlemen’s Magazine in 1771: “About forty years ago, Mr. Williams, an African of fortune, who dressed like other gentlemen in a tye wig, sword, etc. and who was honoured with the friendship of Mr Chelselden [Dr. William Cheselden (1688-1752)], and other men of science was admitted to the meetings of the Royal Society and, being proposed as a member, was rejected solely for a reason unworthy of that learned body, viz. on account of his complection.”

In fact, Carretta dug into primary sources and found that Francis Williams was born the second or third son (he was a twin) of John and Dorothy Williams, a free black couple on Jamaica. John Williams, apparently a former slave, was an established property-owner and trader. In 1708, 1711, and 1716 the colony’s legislature passed laws granting the Williams family legal privileges usually reserved for whites. So already their presence threatened the traditional social structure.

Carretta found that “The register of Lincoln’s Inn in London...records the admission on 8 August 1721 of ‘Francis Williams, youngest son of John W., of Jamaica, merchant,’ confirming the statement of the anonymous author of An Inquiry [into the Origin, Progress, & Present State of Slavery (1789)], though no record has been found of his actually having attained a law degree.” John Williams died in 1723, leaving an estate worth £12,000. Francis soon returned to Jamaica to take up his inheritance.

In 1724, Francis Williams got into a fight with a white man named William Brodrick, who then petitioned the Jamaica legislature to end the Williams family’s legal privileges because they were “of great encouragement to the negroes of this island in general.” The legislature did that in 1730, after the First Maroon War had broken out. Williams protested to the Privy Council in London, insisting it was already “Notorious that no Free Negro [could] wear a Sword or Pistols besides himself.” In November 1732 the council recommended that Jamaica repeal its new law.

Long claimed that Williams set up a school to support himself, but there’s no evidence for that. Instead, he appears to have lived off his inherited property. He wrote poetry on public occasions, and remained a local curiosity. When he died, Williams owned fifteen slaves, but his home was rented and his entire estate worth £525.

The picture of Williams at the upper right comes from the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. I bought a postcard of it a few years ago, not knowing anything about him at the time. The museum’s page on the painting says:

Some writers have suggested that the painting is a caricature of Francis as he has been depicted with a large head and skinny legs. . . . Other critics have considered that the ‘unnaturalistic’ depiction may have been intended to emphasise the subject’s intellectual skills over his physical stature (Francis was alive at the time of the painting’s creation and may even have commissioned it). It may, more simply, be a reflection of the artist’s limited skills.